Women get unnecessary periods on the pill because of the Catholic church

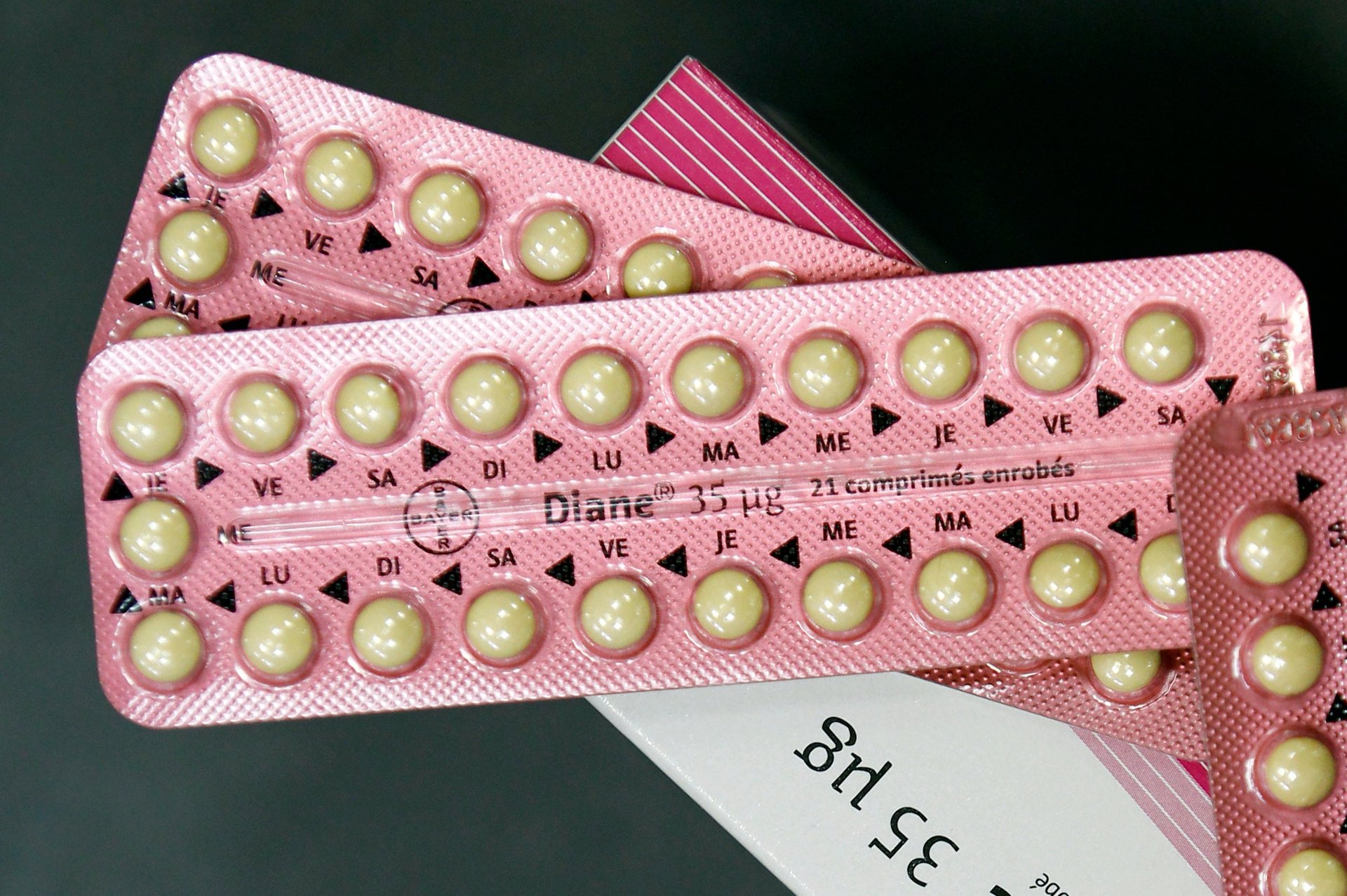

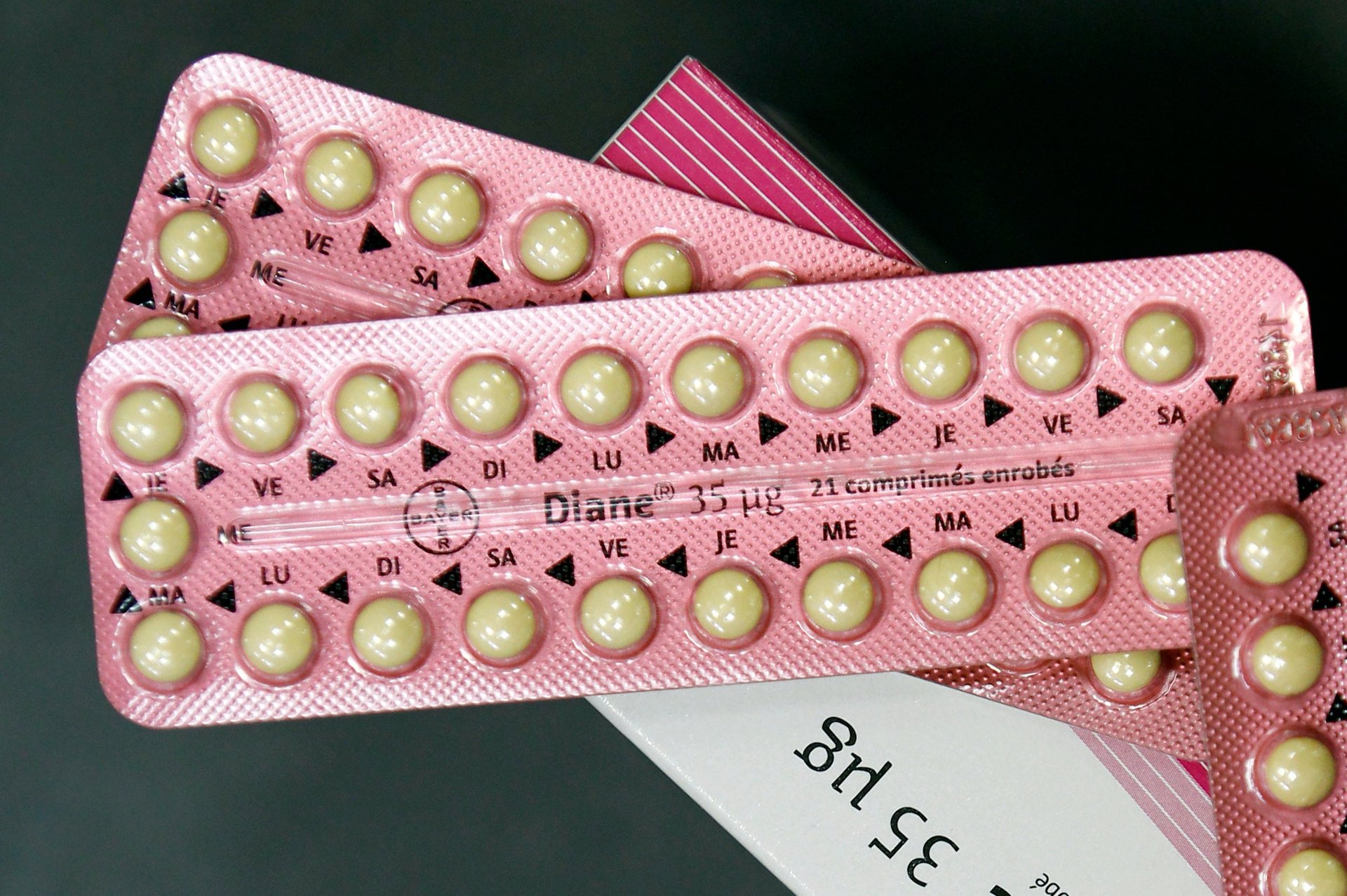

Many women in the UK were this week left reeling after the National Health Service changed its official guidance on how the contraceptive pill is prescribed. In the past, women have taken 21 daily hormonal pills, followed by seven days of a sugar placebo, during which they experience withdrawal bleeding. (Some women take no pills at all during this time.)

Many women in the UK were this week left reeling after the National Health Service changed its official guidance on how the contraceptive pill is prescribed. In the past, women have taken 21 daily hormonal pills, followed by seven days of a sugar placebo, during which they experience withdrawal bleeding. (Some women take no pills at all during this time.)

The NHS now officially advises women to take the hormonal pills continually. Doing so may not only make the pill more effective—fewer hormone-free periods may reduce the risk of unwanted pregnancy—but also alleviate a host of needless side-effects, ranging from mood swings to menstrual cramps.

What many people may not realize is that there was never any scientific underpinning to the week-long “period.” One of the inventors of the contraceptive pill was American doctor John Rock, a devout Catholic who believed that his work would be embraced and celebrated by the church. Rock’s religious beliefs didn’t just inspire the invention of the contraceptive pill—they shaped how it is used to this very day.

Rock saw himself as a pioneer who was doing God’s work. In his 1963 book The Time Has Come: A Catholic Doctor’s Proposals to End the Battle over Birth Control, Rock attempted to represent the pill as simply an “adjunct to nature.” Rather than introducing any foreign barrier into the equation, women were simply regulating their natural cycle and taking the “rhythm method” into their own hands. “If there is no free egg and no fertile period, there is no contraception,” Rock explained to the New York Times in 1966. “The pill modifies for the egg the time sequence in the body’s functions and stretches out the infertile period. It is this inertial period which is the theological basis of the rhythm method approved by the church.” A semblance of “natural” periods would be maintained via a withdrawal bleed to continue this illusion of natural contraception.

Rock seems to have genuinely believed that his work would put to bed one of the Catholic church’s most contentious issues. He was deeply devout, attending mass daily and displaying a large crucifix above his desk, but had an outspoken dislike for “stuffed shirts” in the church who valued doctrine over human life. (In one instance, a woman was advised not to have a life-saving hysterectomy by her priest, who claimed she would be “breaking Catholic precepts.” Rock was eventually granted permission to perform the hysterectomy by a more senior member of the church.)

But the Catholic church did not come round to Rock’s way of thinking. In 1968, after years of deliberation, Pope Paul VI put out his Humanae Vitae encyclical. He was uncompromising: Sex within the Catholic faith must be open to the “transmission of human life.” Marital relations that were “deliberately contraceptive,” by contrast, were “intrinsically wrong.” Worse still, he wrote, sex for pleasure alone could only precipitate a slide in moral values, conjugal respect, and even the sanctity of marriage.

The church never did relent—though Rock eventually left the church over its decision. “When his campaign to get the pill accepted by the Pope failed, he just simply stopped being a Catholic, having been a committed one for his entire life,” reproductive health professor John Guillebaud told The Telegraph. Rock’s loss of faith was perhaps the least serious casualty. Instead, for some 60 years, women have been taking the pill in a “sub-optimal way”—the result of a misplaced effort to please and placate the Pope.