Automation will change every job, but only 25% are on the chopping block

Automation is coming, but not for everyone. Researchers at the Brookings Institution estimate just 25% of occupations in the US—in production, food service, and transportation—are at “high risk” for losing jobs from the advance of automation. “Automation is not the end of work,” said Mark Muro, policy director for the Brookings Institution’s program on urban economies and co-author of a study published Jan. 24.

Automation is coming, but not for everyone. Researchers at the Brookings Institution estimate just 25% of occupations in the US—in production, food service, and transportation—are at “high risk” for losing jobs from the advance of automation. “Automation is not the end of work,” said Mark Muro, policy director for the Brookings Institution’s program on urban economies and co-author of a study published Jan. 24.

Most occupations will see specific tasks assumed by machines, but much of their labor will likely be enhanced, rather than fully replaced, through automation, the study found. That’s because automation rarely replaces entire jobs, but instead handles specific tasks in occupations that often require hundreds of them. In spite of ATMs, America’s 480,000 bank tellers (paywall) are still quite busy walking customers through more complex transactions.

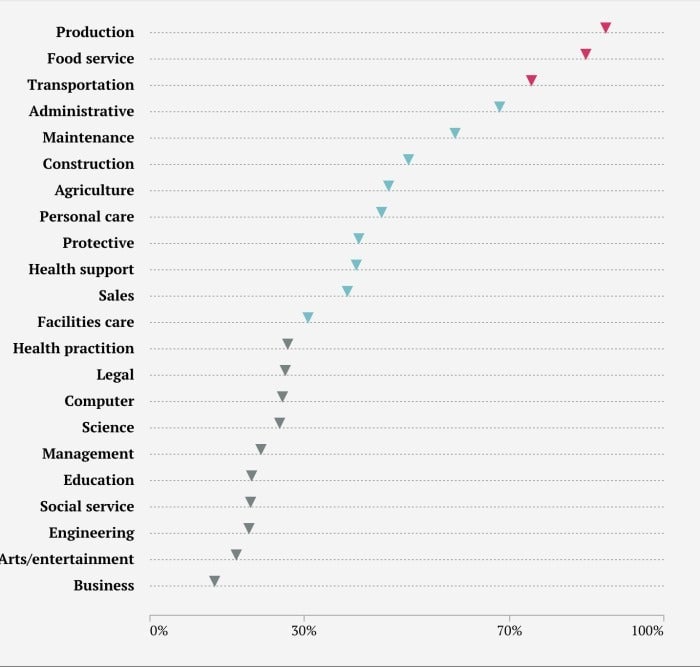

That makes the problem of automation not about the net loss of jobs, but about matching displaced workers with work. To forecast the effects, Brookings researchers looked at thousands of specific tasks within each occupation, and the degree to which automation could handle them, coming up with a risk rating for each occupation (see below).

The workers most vulnerable are in transportation, production, food preparation, and office administration, which, combined, make up about 36 million jobs, or 25% of the total jobs in the US today. In these occupations, roughly 70% of tasks were considered routine and predictable, prime targets to be managed by machines. The most vulnerable were “packaging and filling machine operators” (100% exposure to automation), food preparation workers (91%), payroll and timekeeping clerks (87%), and light-truck and delivery drivers (78%).

Share of tasks vulnerable to automation

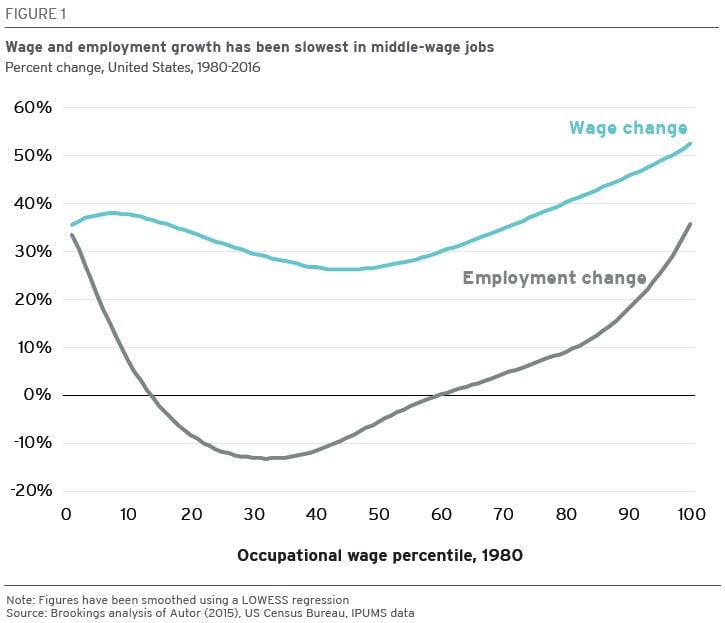

The political turmoil now roiling Western democracies is, in part, traceable back to the hollowing out of the US middle class after the last wave of automation in the 1980s and 1990s. In that wave, personal computing and software automated many routine office and manufacturing tasks. The current wave of automation, driven by artificial intelligence and robots, is different, but is unlikely to be any less disruptive.

Though we may end up with more jobs than we started with at the end of this wave, the same people hit hardest last time—minorities, young people in their 20s, and downwardly mobile men—will come under the most pressure again. That may make today’s political and economic troubles a preview of what’s to come.

To get ready, the Brookings Institute crunched about 50 years of data from the US Census Bureau and Department of Labor to better understand the last wave of automation, and how the next one is likely to be different. Researchers analyzed employment and wage figures for 800 occupations between 1980 and 2016, and made forecasts for states, counties, and cities.

Since the 1980s, they found, a 30-year “IT automation wave” created more jobs than it destroyed. Between 1980 and 2016 in the US, the ratio of jobs to civilian population over age 16 increased from 55% to 57% the report stated (pdf). It’s a similar process that occured with the arrival of mechanized looms in the 1800s. As fabric prices fell, clothing sales rose, and the total number of textile jobs increased—more money into the pockets of employed workers means they purchase goods and services.

But the benefits of the IT automation wave were not evenly distributed. The destruction of manufacturing and clerical jobs in the US fell disproportionately on a single group: workers without extensive education or skills. During the 1980s and 1990s, these auto workers and secretaries lost their jobs, and many were forced to take less lucrative and less secure work in areas like food service, home care, cleaners, and health aides, and recreation.

Digital technology “hollowed out” the US middle class over this period, states Brookings. Wages and employment grew for the top and bottom of the economic ladder, while many in the middle-class saw jobs vanish and wage growth stagnate:

Now, automation in the 21st century is taking aim at the bottom of the ladder. “Near-future automation potential will be highest for roles that now pay the lowest wages,” states Brookings.

By contrast, the technical and creative middle-class jobs of today—many of which require a college degree—are better protected. Non-routine jobs at the bottom of the income scale requiring social or emotional interactions, such as home and personal care, are as well.

Brookings says no one knows how fast this will play out. A complex interaction of automation efficiency, prices, customer preference, and quality improvements are all at play. But we’re likely to get a preview when the next recession hits. Businesses cut back and invest in automation in tight economic times to push down labor costs.

It’s a good bet the highest degree of automation will be among the lowest earners, many in the small and medium towns of the industrial Midwest, which tend to be heavily reliant on just a few factories and industries.

Such displacements will come with political fallout, a trend repeated over and over since the Industrial Revolution. One of the first examples is the Luddites’ rebellion in 19th-century England. In the 1800s, skilled, middle-class, textile workers began protesting the loss of jobs as mechanical looms began to overturn their industry. After trying to negotiate a managed transition with a social-safety net, the Luddite movement began months of “machine breaking,” smashing weaving frames, in a last-ditch effort to bring the new factory bosses to the table.

But at the behest of the factory owners, the British Parliament sent 14,000 troops to the English countryside to put down the uprising. The soldiers executed or exiled dozens of leaders of the Luddite movement. The crushed rebellion cleared the way for the horrific working conditions of the Industrial Revolution. Today’s occupational laws and social security system—ideas proposed by the Luddites—ease some of the worst issues of the previous era. But the same tension remains.

“‘If you want to preserve the dynamism of the innovation economy, you need to make it tolerable for people,” says Munro. “We’re fully immersed in a disruption economy, and gouging the social side of things. A side-effect is the substantial breakdown of the political system.”