Global warming will hit states that support Donald Trump the hardest

Will US Republicans stop refusing to act on climate change if it hits red states the hardest? We’re about to find out. Scientists measuring the impacts of climate change predict the states and counties that have strongly supported Donald Trump and Republican congressional candidates in the last two elections will suffer more than those that did not.

Will US Republicans stop refusing to act on climate change if it hits red states the hardest? We’re about to find out. Scientists measuring the impacts of climate change predict the states and counties that have strongly supported Donald Trump and Republican congressional candidates in the last two elections will suffer more than those that did not.

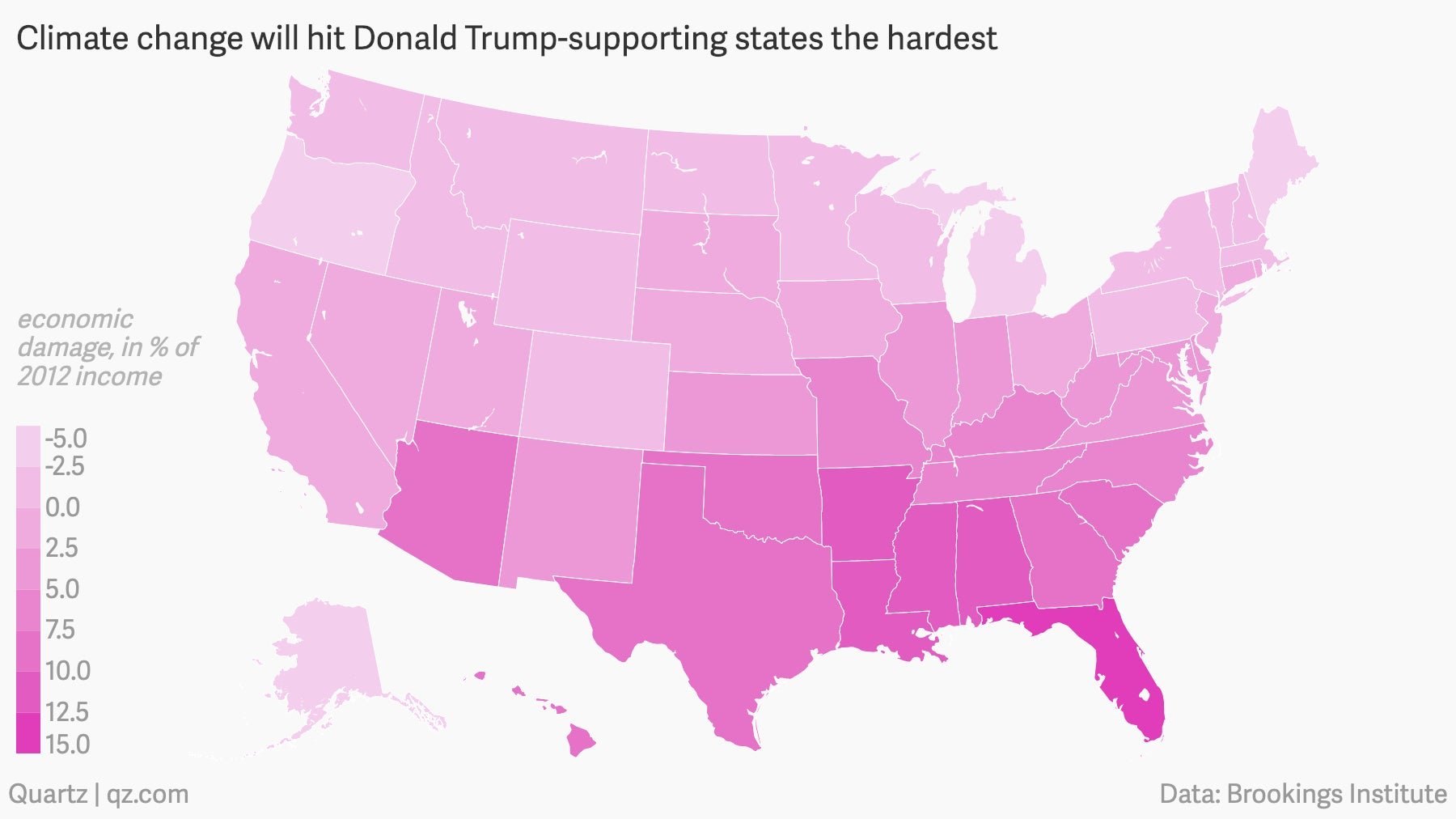

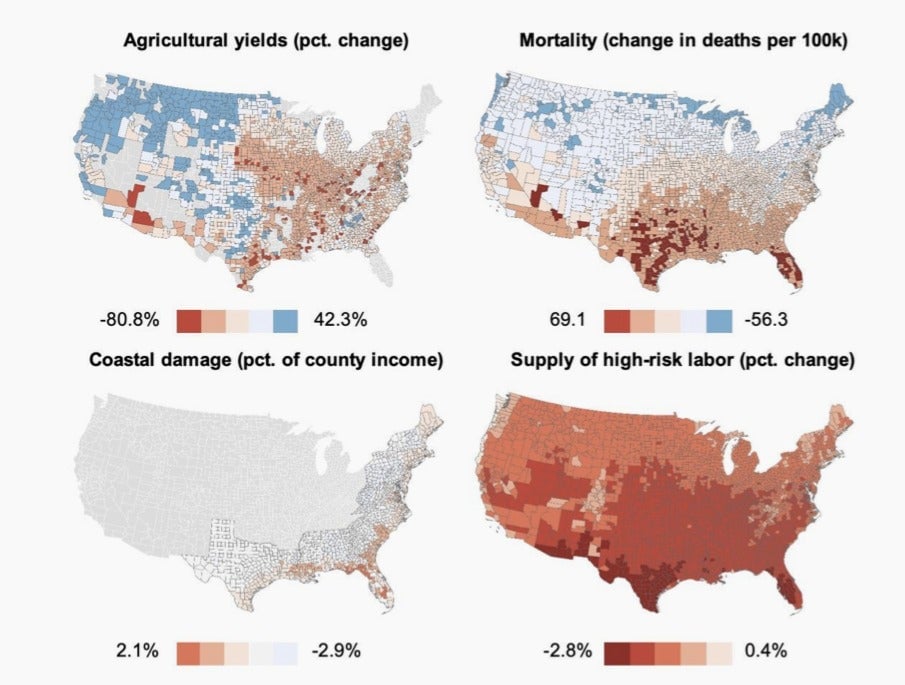

The Brookings Institution released a study today (Jan. 29) showing that in districts backing Republicans for House of Representative races in 2018, the expected economic damage was 4.4% of 2012 incomes compared to 2.7% in districts that elected Democrats. Overall, regions that backed Trump in 2016 are expected to absorb 1.5 percentage points more in economic damages than those that supported Hillary Clinton. At the forefront will be the southeastern states of Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Florida, which will suffer economically thanks to decreased agricultural yields, and increased mortality (due to heat waves), coastal damage, and harm to workers (such as heat stroke).

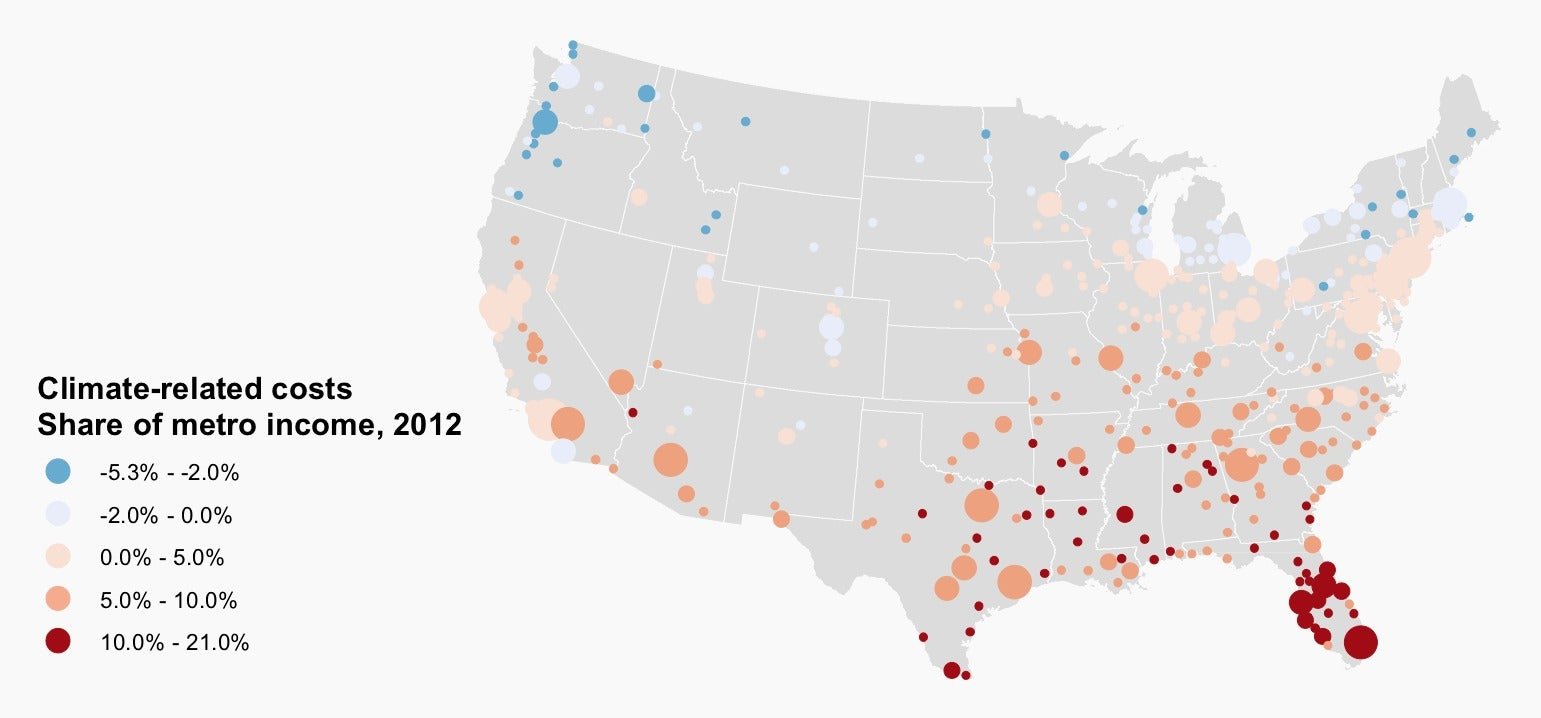

The study looked at county-level impacts supplied by the Climate Impact Lab, a collaboration by 30 climate scientists, economists, and researchers from many top US research institutions. The map forecasts climate-related costs up to the end of the century as a share of 2012 county income.

The predicted hardest-hit US cities are mostly clustered in Florida and Texas, with a few more spread out the southeast. Flooding in Florida (which is already occurring) will inundate one in 10 homes every other week by the end of the 21st century. By comparison, some northern states may even see modest economic benefits as temperatures rise and growing seasons in those regions expand.

Will this change the mind of anyone living in Trump country? Not anytime soon, says Josiah Neeley, an energy fellow at R Street Institute, a libertarian, nonpartisan think tank based in DC. “We’ve seen for a long time that areas that are mostly likely to be negatively impacted by climate change aren’t necessarily the ones with the strongest support for climate action,” he wrote by email. “This is why policies to address climate change need to be able to appeal to people on non-climate grounds, such as economic development or increased energy security.”

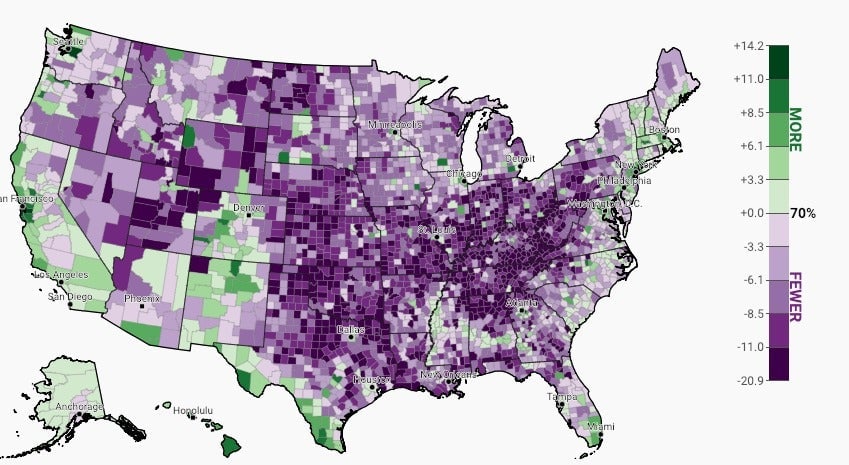

But Anthony Leiserowitz, director of Yale University’s climate change communication program, says the urgency of climate change is starting to break through to the general public. Seventy percent of the country now believes global warming is happening, while only 14% still deny the scientific evidence that shows the planet is warming rapidly as a result of greenhouse gasses released by humans.

The remaining skeptics are geographically concentrated in the midwest and high plains of Texas, Oklahoma, Nebraska, and Indiana. Notably, many coastal districts, such as those in peninsular Florida—which will be among the hardest hit—are more moderate on the issue. This map shows the deviation in opinion from national average for public opinion on the question: “Is global warming happening?”

Leiserowitz says the sense or urgency to act on climate change is growing. Based on Yale’s research, only 9% of the US population is “firmly entrenched” in climate-change denial. The rest of the public, Leiserowitz says, is gradually realizing the threat posed by climate change, and the need to act after nearly a decade of extreme, destructive weather. “Many Americans are beginning to ask themselves, ‘What is going on with this extreme weather?” says Leiserowitz. “And the media is beginning to incorporate the occasional story in these extreme events when scientifically appropriate. Climate change is here and now.”

Just don’t call it “climate change,” says Colin Wellenkamp, executive director of the Mississippi River Cities and Towns Initiative. The issue is so politically polarized, it’s virtually impossible to navigate on those terms. But natural disasters have relentlessly struck many regions of the US in recent years. The Mississippi River valley, for example, has lost between 3% and 8% of its economic output every year thanks to disasters ranging from the drought of 2012 (a once in half-century event) to Louisiana’s 1,000-year rain event in 2016. “We’re experiencing it over and out again, and it’s getting worse over time,” says Wellenkamp.

People in the region are generally opposed to climate responses that increase costs, Wellenkamp says, but combining these with more jobs or other economic benefits can work.

City mayors up and down the Mississippi River valley, after facing $200 billion in climate-related damages over the last decade, have come together to take their steps in their own way. Regardless of the hostility in Washington DC, these mayors, many of whom are Republicans, are acting anyways. They’re building greenways and wetlands to manage flooding and absorb carbon dioxide. They’re incentivizing more sustainable agriculture to boost yields and reduce emissions. Cities are increasing density and adding public transit options to reduce overall carbon emissions.

“[The mayors] are very engaged with climate action,” says Wellenkamp. “They just don’t call it ‘climate action.’ They call it ‘disaster resistance,’ or ‘resilience’ or ‘disaster preparedness.’ If the sole purpose is to remove carbon in the atmosphere, you’re going to have a hard time selling them.”