Thanks to Detroit’s bankruptcy ruling, state pensions just got a whole lot riskier

The news out of Detroit on Wednesday, Dec. 3, might alter state pensions the same way the Enron bankruptcy changed 401(k) accounts back in 2001. According to the Judge Steven W. Rhodes:

The news out of Detroit on Wednesday, Dec. 3, might alter state pensions the same way the Enron bankruptcy changed 401(k) accounts back in 2001. According to the Judge Steven W. Rhodes:

“Pension benefits are a contractual right and are not entitled to any heightened protection in a municipal bankruptcy.”

This is shocking because in many US states, including Michigan, pension benefits are guaranteed by the state constitution. Each year you work, you accrue a larger pension benefit based on your tenure and salary. The guarantee not only promises the new accrual, but also that once you’ve started work, you’ll accrue future benefits at the same rate until you retire.

Until today that guarantee meant people assumed the benefit was risk free, meaning you get your pension no matter what happened to markets or your city. This sort of guarantee is extremely valuable—it was like free insurance. But states and municipalities assumed they could provide that insurance for free. That meant many states and municipalities, not just Detroit, over-promised and gave away perks they couldn’t afford.

The bankruptcy in Detroit and the resulting need to revisit pension promises is precisely what happens when you don’t adequately account for financial risk. It is similar to the counter-party risk that was realized in the financial crisis. In that case, too, people counted on an asset paying off no matter what happened to markets, but whoever sold them the promise didn’t account for how much the guarantee really cost.

The ruling in Detroit will force people in other states and municipalities to realize the fragility of their guarantee—and this is just the beginning. Economists Josh Rauh and Robert Novy-Marx estimate in the next 10 years we’ll see many other states and municipalities run out of money to pay benefits. Before today it was assumed the benefits would be paid at the expense of other services, now that’s not as certain.

Some state employees, including the fireman in Detroit, don’t even have Social Security. They are entirely exposed to the financial management of their state or municipal pension board. When Enron went bankrupt, many employees were distressed to discover their 401(k), which was invested heavily in Enron stock; they lost their job as well as their retirement account. Now, there’s greater awareness that this is bad idea and default investment rules encourage better diversification.

Realizing the true risk in state-defined benefit pensions today could have equally profound consequences as pensioners realize they are more vulnerable than they thought. For example private accounts like 401(k) or 403(b) plans, where individuals explicitly bear the risk, may become more palatable. At least the assets are yours, under your control, and by definition fully funded. As a guest on Wisconsin public radio, I was surprised a few callers (wholly dependent on their state pension) lamented they didn’t have a private account to fall back on.

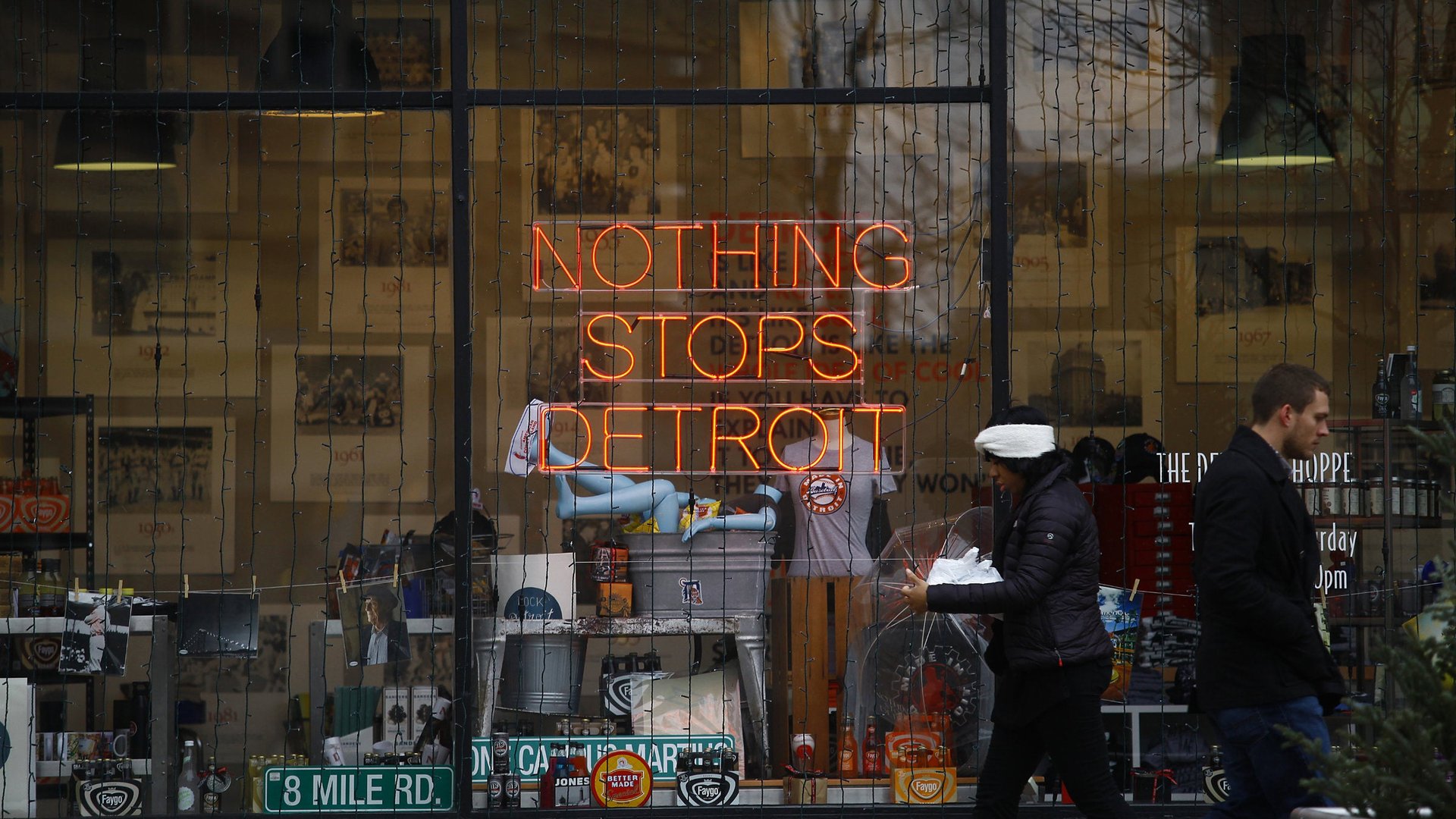

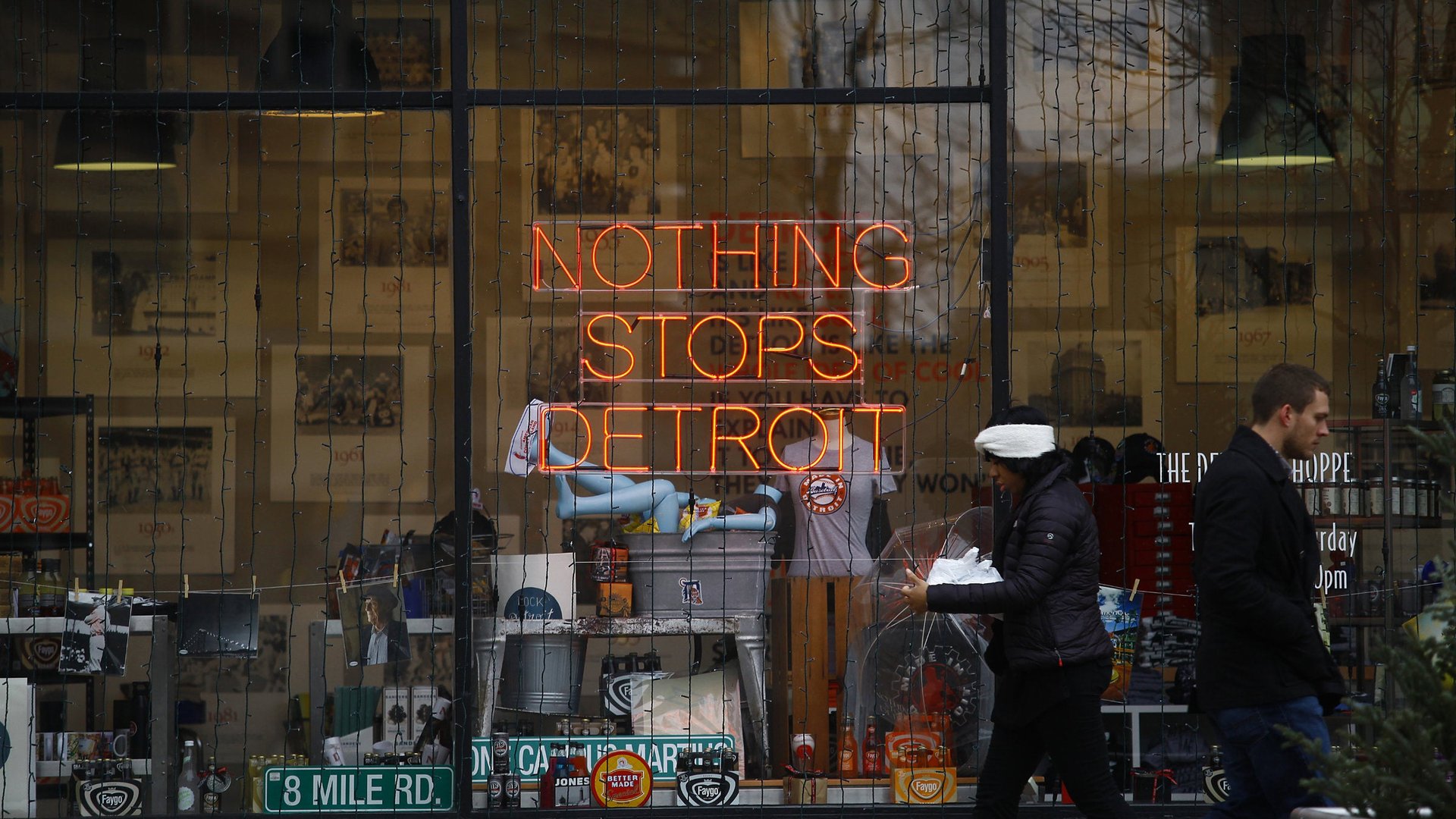

The silver lining is that states and municipalities might start to account for the true cost of what they have promised. If they can’t afford to make those promises, with today’s ruling, there’s now scope to lower accrued and future benefits to something more realistic. But it may be pensioners in depressed areas who pay the price.