Trump could cost the US the World Bank presidency for the first time

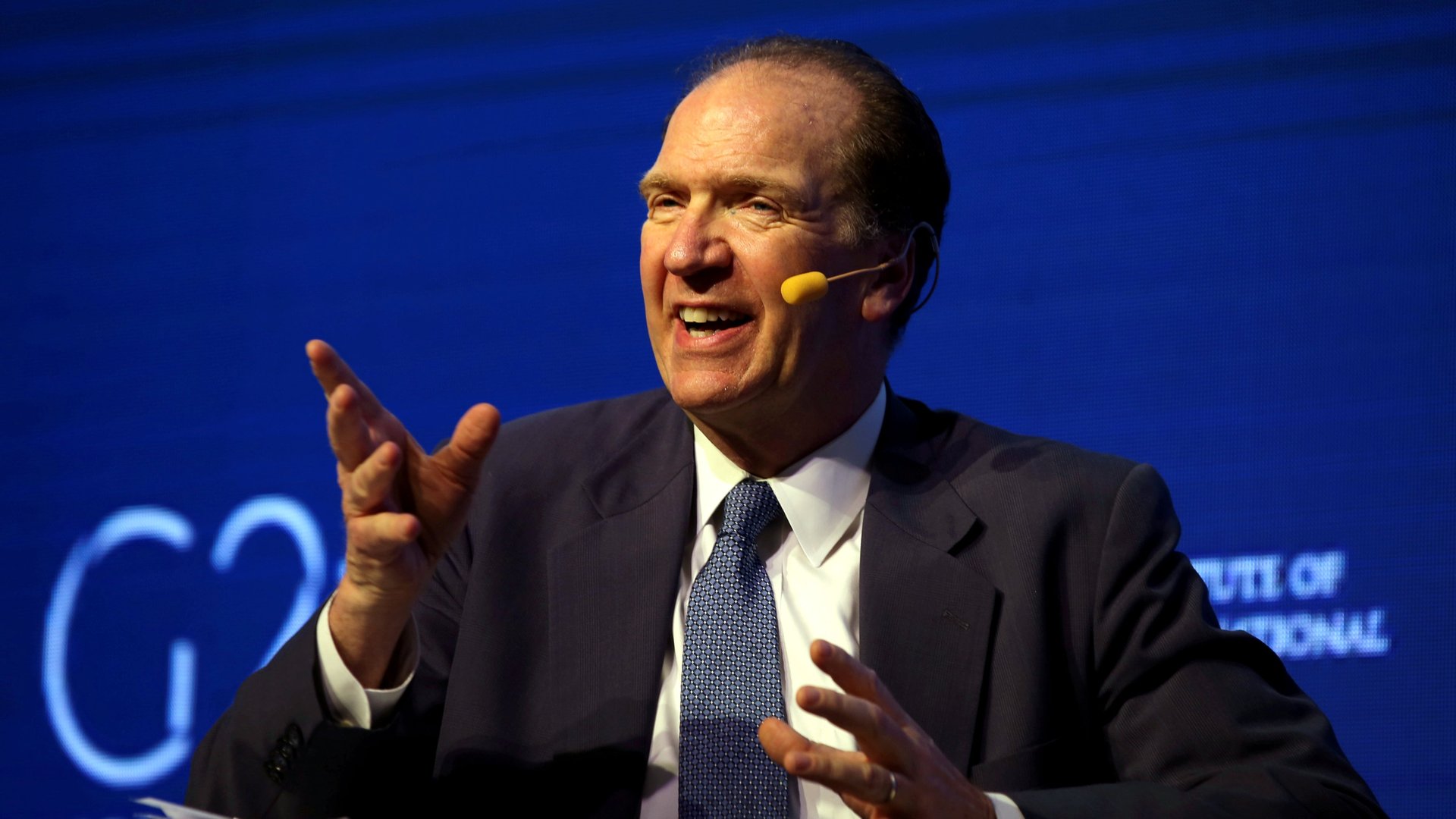

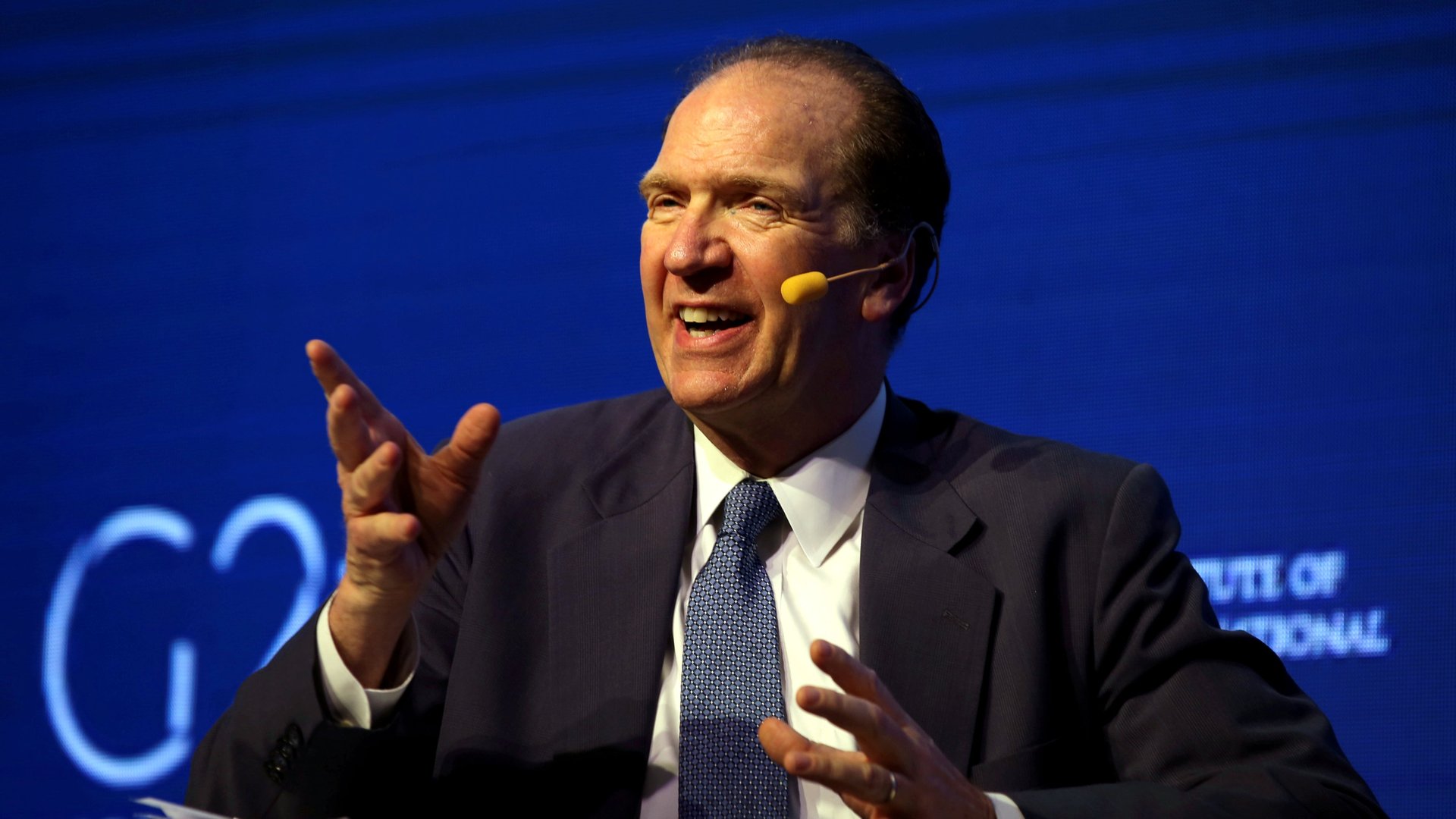

Donald Trump is preparing to select David Malpass, a Treasury official, as the US nominee to lead the World Bank, a move predicted to hasten the end to a 72-year-old tradition of US leadership at the global development finance agency.

Donald Trump is preparing to select David Malpass, a Treasury official, as the US nominee to lead the World Bank, a move predicted to hasten the end to a 72-year-old tradition of US leadership at the global development finance agency.

It’s an extremely Trumpy move, because Malpass is a critic of international development. Like placing public-housing skeptic Ben Carson at the head of the Department of Housing and Urban Development, or pay-day-loan darling Mick Mulvaney in charge of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the move signals a hearty desire to disassemble the institution from within.

Malpass, now the Undersecretary of the Treasury for International Affairs, was the chief economist at Bear Stearns when the investment bank failed at the outset of the 2008 financial crisis. He famously warned investors, “don’t panic about the credit market” in 2007. Development economist Justin Sandefur says “his disdain for the World Bank’s mission of fighting global poverty rivals John Bolton’s respect for the United Nations.”

The problem with the pick, as Mark Leon Goldberg notes, is that it doesn’t face confirmation in the docile Republican senate, but instead in the fractious community of nations. The World Bank is guided by its international shareholders, and even though the US holds more than 15% of the voting shares, it must assemble a majority.

Traditionally, an American has held the presidency of the World Bank, while a European has lead the IMF. But, if Trump thumbs his nose with a nominee like Malpass, the European countries who typically back the US candidate may give in to growing pressure to select a leader for the bank from Asia, Africa, or South America.

That was likely to happen anyway. Both the World Bank and the IMF, born of the post-World War II American economic hegemony, have been under pressure in the changing global economy. So-called emerging market countries have increasingly argued for a greater voice in the governance of these institutions as their own economic clout has grown.

In 2015, we asked outgoing World Bank president Jim Kim if he foresaw a non-American taking on the role in the future, and he predicted that “you will never again see an IMF or a World Bank election without very strong contention, coming especially from the developing world.” That contention is only going to grow.

The World Bank in particular has seen its original purpose—economic development loans—upended by the private capital markets. Under Kim, an American physician and public health expert nominated in 2012 by president Barack Obama, the World Bank attempted a pivot to focusing on health and education, and away from the traditional big infrastructure projects of its heyday. Few see that shift as successful.

Despite criticism from inside and outside the agency, Kim’s uncontroversial appointment to a second five-year term in 2016 had been seen by some development insiders as an attempt to stave off a Trump appointee. Kim left the post on Feb. 1 in a surprise decision to, ironically, work at a private firm that makes infrastructure loans in emerging markets.

Referring to the IMF leadership and the informal rotation of UN general secretaries from different regions of the globe, Kim also told us that “if one part of the system breaks, all of the other parts of the system may break, too.” And indeed, this may be part of the intention of Trump and his advisors, who show little favor for international rules and institutions that they see as hindering US action.