Self-harm images on Instagram show how difficult it is to police content online

This post has been updated after Facebook changed its policies Feb. 7.

This post has been updated after Facebook changed its policies Feb. 7.

After the UK’s health secretary Matt Hancock told tech companies to clean their platforms from content containing self-harm, threatening regulation, Adam Mosseri, Instagram’s head, announced the app would roll out “sensitivity screens” that would block images and videos of people cutting themselves.

Both moves come after the father of a 14-year-old girl in the UK said that he believed that Instagram contributed to his daughter’s 2017 suicide. “I have been deeply moved by the tragic stories that have come to light this past month of Molly Russell and other families affected by suicide and self-harm,” Mosseri wrote in an op-ed for The Telegraph on Monday (Feb. 4).

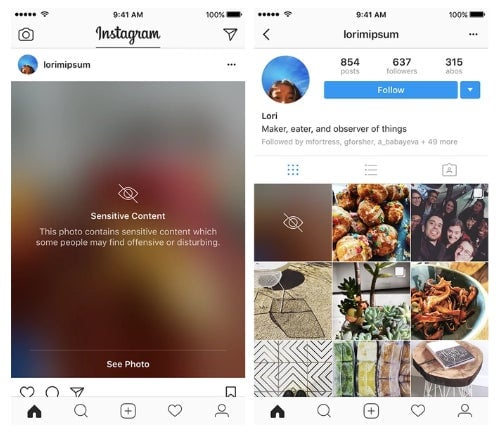

Users should start seeing the screens this week for content that contains cutting. The company first announced plans for “sensitivity screens” in 2017, and started applying them to other “sensitive” content like images of animal abuse posted by humanitarian organizations. They blur out the content behind them and contain a message about its sensitive nature. The images won’t be outright banned, however: “We still allow people to share that they are struggling,” Mosseri wrote. The app’s policy only bans images that “glorify” self-harm.

(Update Feb. 7: Instagram is banning all images of cutting, the company said in a blog post, and hiding non-graphic images of self-harm like scarring, from search results, hashtags, and Explore. These images won’t be removed entirely, because the platform doesn’t want to “stigmatize or isolate people who may be in distress and posting self-harm related content as a cry for help.” The changes were made “following a comprehensive review with global experts and academics on youth, mental health and suicide prevention,” it said in the post. It is still consulting experts on what else it can do, which may include sensitivity screens for the non-graphic images of self-harm.)

Whether an image shows self-harm, encourages it, shows ways to raise awareness or to reach out for help can be a difficult line to draw. Right now, it’s not hard to find images of cutting or scarring on Instagram. Some of the images show the person’s recovery, some clearly show users in the thick of it. Mosseri acknowledges this. “The bottom line is we do not yet find enough of these images before they’re seen by other people,” he wrote. Instagram relies on users to report self-harm content, but Mosseri says the platform is investing in technology that helps with detection.

When asked about what experts were consulted on the new policy, an Instagram spokesperson said that the company was in the midst of a review of its policies with external experts. Mosseri says in his post that the platform has “worked with external experts for years to develop and refine our policies.” (Facebook has since provided a list of experts it consulted, which is available here.)

It’s not clear whether there is a cause-and-effect relationship between being exposed to self-harm behaviors and engaging in them, Lindsey Giller, a clinical psychologist at the Child Mind Institute in New York, told Quartz. However, if someone is vulnerable or had already started harming themselves, seeing similar images can “definitely” be triggering, and even cause them to go back to these behaviors, she added.

This is why, Giller noted, psychiatric hospitals have a policy of asking those with scars or wounds on their arms to wear long-sleeved shirts, or to otherwise cover up.

Sensitivity screens are a “very valuable step in trying to protect young people from images that might be triggering for those who are already vulnerable,” Giller said, although she said she thought that a lot of these kids would likely click right past such a screen, continuing to seek out these images.

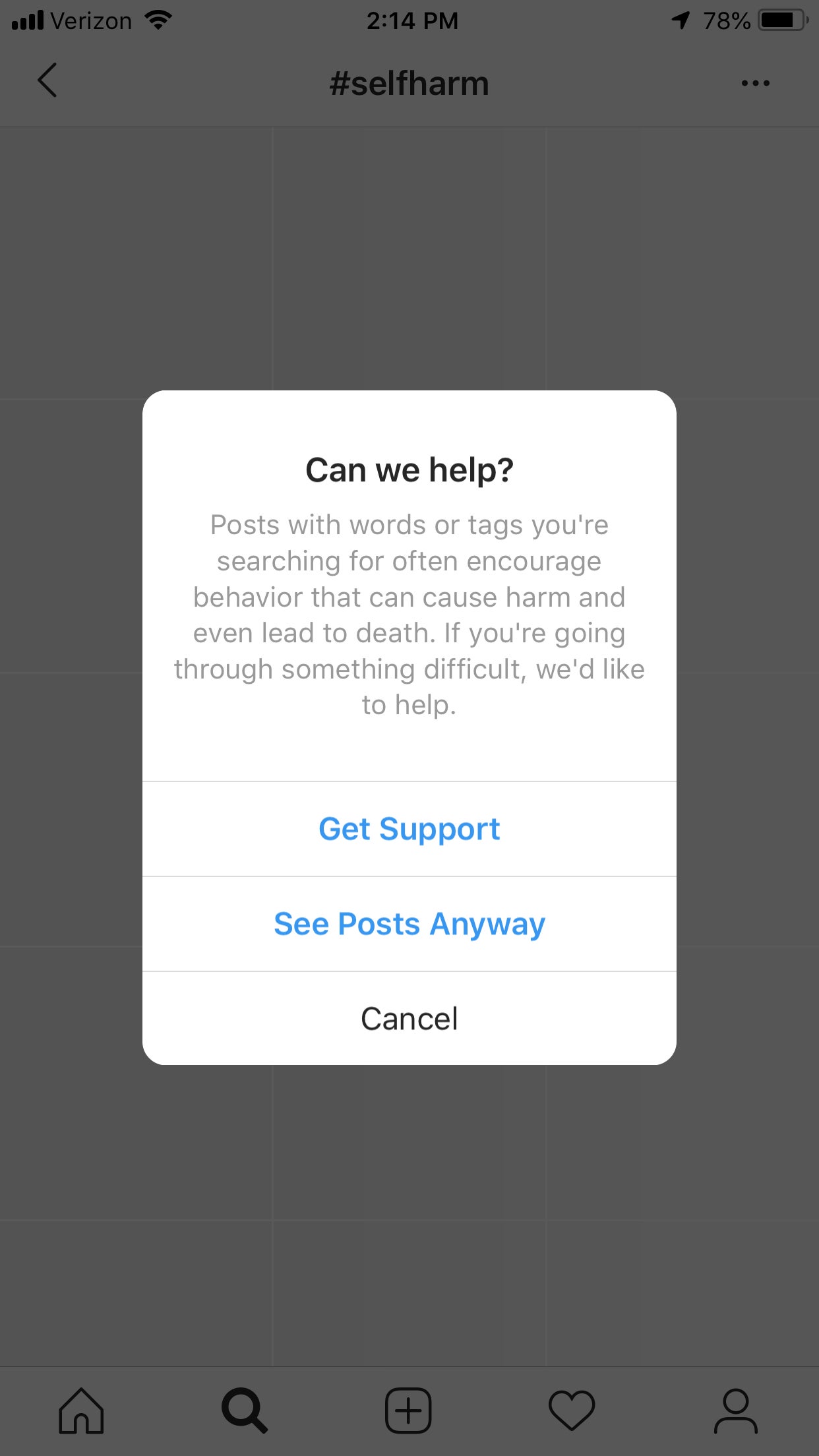

Right now, Instagram shows users searching for the hashtag #selfharm or #cutting a message asking them if they need help, and directing them to a special screen with options to talk to a friend, talk to a helpline, or get tips. (It also has measures that stop recommending related images, hashtags, accounts, and search suggestions.) These are also helpful, Giller said, although ultimately hearing about others’ struggles directly from them might be more powerful.

Instagram has to figure out how to treat the exceedingly fine line of leaving these messages up, but also how to approach images that might be triggering.

Mason Marks, a legal scholar who has researched Facebook’s suicide prevention efforts, said he would err on the side of less censorship, because it stigmatizes the issue of self-harm. “What does this say about people who are engaging in that kind of behavior? It sends the message that this is something bad that we shouldn’t be talking about,” he said. “We should talk about it more openly.”