America First, meet Asia First

America can’t become great again without Asia.

America can’t become great again without Asia.

President Xi Jinping’s announcement that China will accelerate its market opening to more American high-tech goods and make greater efforts to protect foreign intellectual property is welcome news for American firms, the stock market, and global trade as a whole. But we shouldn’t confuse blips and trends.

The long-term trajectory is clear: Asia is not just rising—it is also decoupling from the US.

The past two decades have witnessed Asia come out of its 1997-1998 financial crisis and rebuilding its economic fundamentals sufficiently to withstand the 2007 Western financial crisis. Here are just a few metrics that indicate growing Asian confidence (and even self-sufficiency) from capital to capacity-building:

- Asian countries generally have lower debt, higher reserves, and manage currencies through trade-weighted baskets rather than US dollar pegs.

- All of the largest holdings of currency reserves are in Asia.

- Japan and China have become the largest international creditors.

- Meanwhile, Asian central banks have boosted the liquidity of currency-swap agreements, and their governments have launched a new set of diplomatic frameworks such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, the Belt and Road Initiative, and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.

- Local currency borrowing has displaced large, outstanding US-dollar-debt obligations, giving governments much more long-term investment capacity with less concern for currency volatility. Not only have Asia’s developing economies thus weathered multiple “taper tantrums” as US interest rates rise, but their own rates are now more correlated to each other and have remained low.

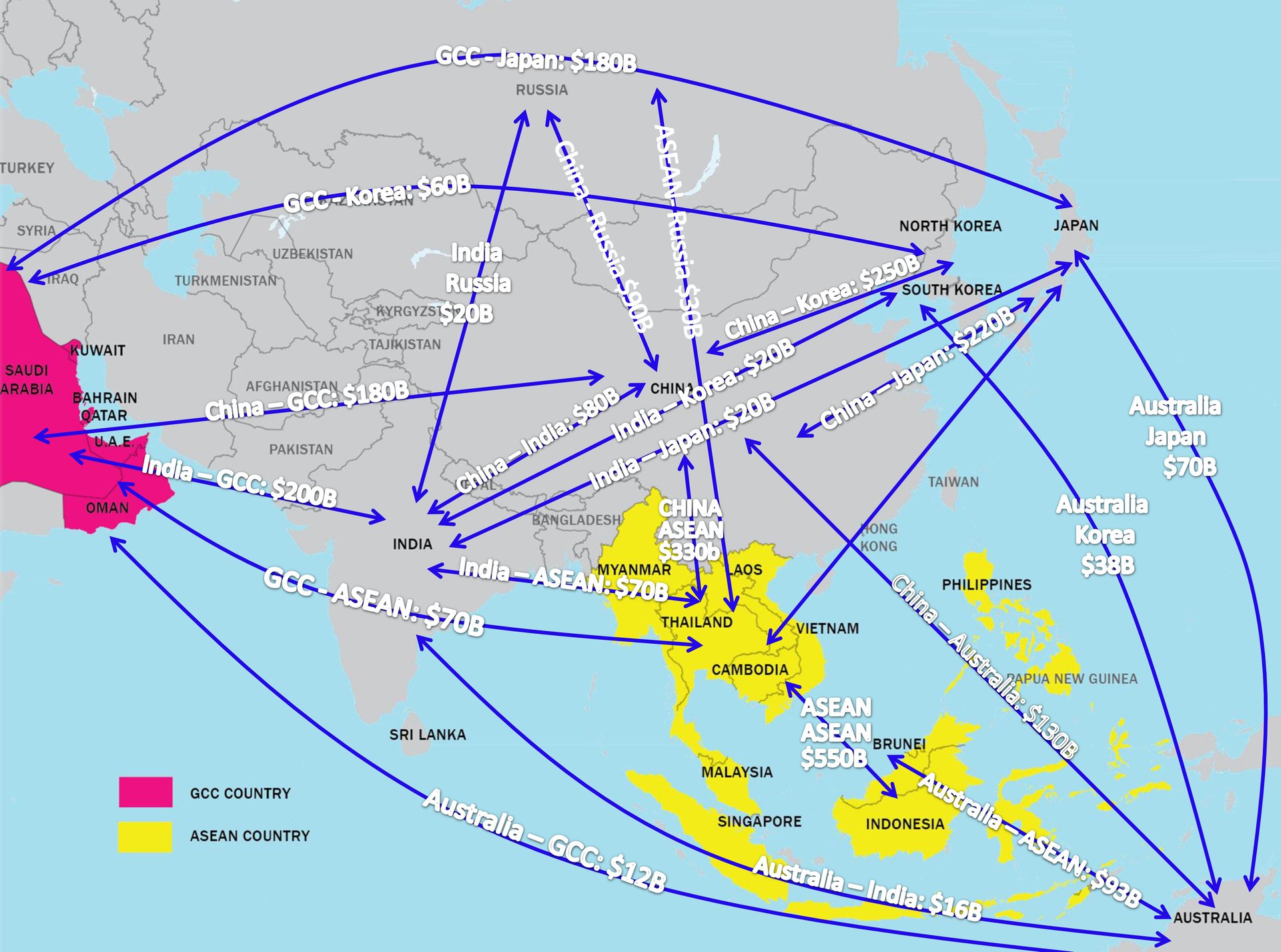

The Asian sphere of intensifying political and economic convergence stretches far beyond China, from the Gulf countries to Japan and Russia to Australia. This geographic Asia is also the strategic Asia, with five billion people—more than the rest of the world combined—looking more toward each other than to Europe or North America.

There is currently $4.5 trillion annually traded in the Northeast Asian triangular among China, Japan, and South Korea, and trade within Asia represents more than 60% of total Asian trade. Asia today is thus becoming what Europe and North America already are: a regional system in which members have more to do with each other than with states from other regions.

The great story of the 21st century is therefore not merely the rise of Asia, but the Asianization of Asia. The Obama administration attempted a “pivot” to Asia, its centerpiece being the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade agreement, which would have pried open Asian markets further to American goods. But with the Trump administration pulling the US out of the TPP, alienating its closest Asian allies such as Japan and South Korea with his tariffs on steel and other vital goods, it’s not clear what America’s role in Asia will be in the decades ahead.

The return of Afroeurasia

Asia in the 21st century most resembles Asia of the 15th century, the pre-colonial era in which East Asian empires, Indian dynasties, Arab caliphates, Indonesian maritime traders, and Mongolian steppe nomads all co-existed in dynamic patterns of commerce, conflict, and cultural exchange.

Before Ferdinand Magellan and the encroachment of Portuguese, Spanish, and Dutch merchant navies, Asians ruled the Indian Ocean waves. Scholars of the more than thousand years of pre-colonial history of this region refer to it as an “Afroeurasian realm” of Silk Roads spanning land and sea, with ethnic intermingling and trade networks spanning East Africa to Korea. The Trump administration’s growing usage of the term “Indo-Pacific” merely reflects the reemergence of this ancient reality.

The more Trump digs in behind his “America First” campaign, the more Asians are wisely hedging against excessive dependence on the US market. They are doing this by increasing trade with each other, which is precisely what China, Japan, and South Korea agreed to last autumn. Unlike the US, Japan and South Korea have relatively balanced trade with China; South Korea even has a significant surplus. And while they are equally concerned with China’s rapid moves up the value chain, their strategy is to boost innovation and aggressively sell more into China. (It is worth noting that Canada and Mexico have enthusiastically joined TPP by the same logic, despite their sizeable deficits with Asian trade partners.)

The tariff escalation between the US and China has convinced Asians that they cannot rely on the US as a risk-free supplier of critical goods. The lesson Chinese firms have taken away from Trump’s export controls on American firms is that they should permanently substitute American high-tech imports with those from these nearer Asian trading partners, with whom they already trade more and have more leverage.

From semiconductors to soybeans, permanent substitution has become Asia’s top priority. Indeed, in the intervening years since Chinese handset and telecom equipment manufacturers signed long-term deals with Qualcomm, Intel, and other American firms, China has decreased its dependency on US suppliers. It now imports nearly 70% of its high-tech goods from Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, and Europeans. The logic of globalization dictates that the more Trump tries to isolate China, the more everyone else—from Canada to Latin America, and Europe to Japan—will do their best to capture America’s market share in China and Asia more broadly.

From America First to America Alone

America First is not working for America. Retailers are raising the cost of goods to consumers, and America’s allies are gaining market share abroad at its expense. America’s manufacturing and agricultural sectors are going to feel the pain most acutely, for reasons that pre-date the trade war but will accelerate the longer it persists.

China’s soybean importers now favor Brazil and Argentina, leaving Trump to spend taxpayer money bailing out American farmers. The only consolation is that Argentina has had to buy American soybeans and ship them onward to China in order to meet China’s massive demand.

America’s factory workers won’t be so lucky. Since most American-manufactured goods—from steel and appliances to electronic equipment and aircraft—can be much more readily substituted by competitors, once foreigners stop buying American, they’re not likely to start again.

Take the example of General Motors. At first, Asia was a bright spot for the US car manufacturer. Earlier this year, GM recorded its highest level of car sales in China, where car ownership is still expanding (though not as rapidly as in recent years). But with the recent headline that GM will be slashing thousands of jobs and closing several US plants, GM will lack the capital to expand in Asia to cope with demand—and to keep pace with competition as companies from Ford to Chevy (as well as European carmakers) race ahead to capture the region’s swelling electric car market.

American firms can only afford to employ more Americans if they have strong global profits, something that can’t happen if American revenues in Asia decline. GE’s plant closures and declining investment are no doubt a blow to Trump’s “Buy American” agenda, but he has only himself to blame. Tariffs on China have raised steel prices across the manufacturing sector, while domestic demand is flat. Then there are the expanded “rules of origin” requirements in the new USMCA agreement (or “NAFTA Plus”), which were intended to benefit the auto sector. But as the Peterson Institute points out, these quotas will actually benefit cheaper steel and auto-part manufacturers, particularly from Asia, while reducing investment in the US and its neighbors.

There couldn’t be a worse time to make access to Asian markets harder for American firms. Asia is experiencing a surge in corporate patriotism, from Chinese smashing Apple iPhones in public and switching to Huawei to Grab taking over Uber’s operations across Southeast Asia and the Luckin coffee chain challenging Starbucks.

To succeed globally, one has to manufacture and sell globally. This is especially true given America’s aging demographics, weak infrastructure investment, and saturated markets. Most Fortune 500 American companies such as Apple generate as much as half or even more of their global revenue from abroad; the American market just isn’t big enough. As Apple loses market share in Asia to local competitors, its market cap is feeling the pinch. American manufacturing will continue to decline unless it embraces Asia by going back to the TPP trade agreement—and hope that China eventually joins it as well.

Asia’s decoupling is great news for Asia, but much less so for the US. America’s share of global trade will slide further below other regions. On the one hand, this reflects the fact that America does not need the rest of the world for its survival. In geopolitics, that is a blessed condition. But in geoeconomics, it means the US is actually much more dispensable than it thinks. Indeed, China’s most significant trade relationships are first and foremost other Asians, followed by Europe, with the US third most important. From China’s standpoint, number three just launched a trade war against number one.

It has taken one short generation for Asia to launch its decoupling from the US—and the coming generation will witness even more couplings among Asians themselves. “America first” sounds like a great idea, except when it actually means “America alone.”

This essay is adapted from The Future is Asian: Commerce, Conflict, and Culture in the 21st Century (Simon & Schuster, 2019), which came out this week.