Cork, shoe polish, and the history of blackface

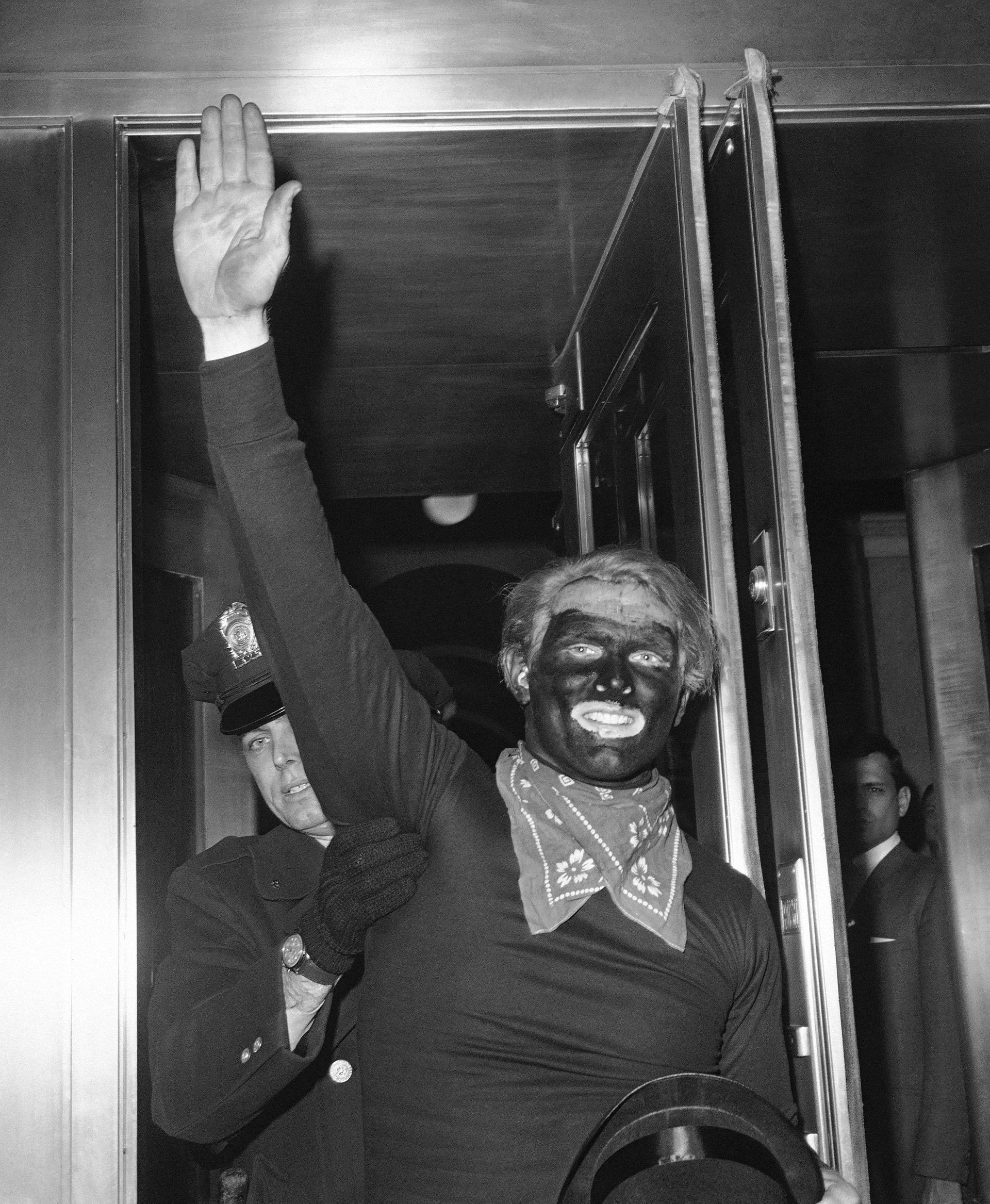

Outrage has taken over the US as it learned last week that Virginia governor Ralph Northam used shoe polish to impersonate Michael Jackson—and possibly posed in a yearbook photo wearing blackface, or a Ku Klux Klan robe. A few days later, it emerged that fellow Democrat Mark Herring, the state’s attorney general, donned a wig and brown makeup as part of a rapper costume. Just yesterday, it was reported that Virginia senator Tommy Norment, a Republican, was the editor of a college yearbook littered with racist photos.

Outrage has taken over the US as it learned last week that Virginia governor Ralph Northam used shoe polish to impersonate Michael Jackson—and possibly posed in a yearbook photo wearing blackface, or a Ku Klux Klan robe. A few days later, it emerged that fellow Democrat Mark Herring, the state’s attorney general, donned a wig and brown makeup as part of a rapper costume. Just yesterday, it was reported that Virginia senator Tommy Norment, a Republican, was the editor of a college yearbook littered with racist photos.

This is disturbing, but should not be shocking: In certain parts of the US, blackface was an entrenched tradition whose racist remnants survive today.

Both men admit what they did was wrong. But that kind of awareness is relatively recent, as history shows.

An American history

Much like slavery, and racist segregation, blackface is permanently entrenched in America’s history, having likely debuted in the 1830s as minstrel shows began to gain popularity.

In the Middle Ages, and especially during the 16th century, a minstrel was a performer that would entertain a royal or aristocratic court with singing and dancing. This role was translated into minstrel shows, arguably the first type of original American entertainment. They featured mock black characters, played by white entertainers, who sang, danced, and performed for an audience. The most famous such characters lent its name to the very phenomenon of post-slavery segregation: Jim Crow. A series of other characters and caricatures—whether in minstrel shows or otherwise—remained in popular culture for years afterward.

It wasn’t until the 1950s, when the Civil Rights movement underscored the offensive nature of blackface, that the practice started losing popularity.

Its powerful racist meaning is encapsulated in this anecdote: In 1965, members of the American Nazi Party entered Congress, interrupting a swearing-in ceremony, and saying, as a way of mocking black citizens, “I’se the Mississippi delegation—wants to be seated.”

Blackface exists outside America, too, and though it holds racist connotations, it is subject to less unequivocal stigma. In Belgium, it is often worn by Santa’s black slaves, and in the Netherlands, blackface wearers impersonating the character Zwarte Piet are a staple of winter holidays. In China, it has been featured in ads and on television. And in opera and ballet across the world—including in the US—it’s not uncommon for performers to wear blackface to portray black characters such as Othello.

A racist heritage

In the US, blackface was especially popular in southern states, so it shouldn’t be surprising that the disturbing heritage lingers on in Virginia. The Northam controversy started over allegations that he appeared in a yearbook picture either wearing blackface or a KKK robe. Northam denied being either of the two people in the incriminating photo, but it was clearly taken in an environment where wearing racist costumes was nothing to be ashamed of—quite the contrary.

Racism is prevalent in the history of many southern institutions, as blogger Black Aziz Anansi showed, by sharing a series of disturbing class photos from the early 20th century, showing all-white classes of Emory University and University of Georgia posing with a black boy, as a mascot of sorts:

To lend evidence to the institutional nature of racism, from 1888 to 2008, the very name of University of Virginia’s yearbook, Corks and Curls, was a direct reference to racist costumes, explains cultural history professor Rhae Lynn Barnes in a Washington Post column. The title borrows from minstrel slang, referring to tools used for racist impersonation: a white person would darken their face with burned cork, and wear a curly wig to mimic an afro.

The name was later revived by a group of students, which published the latest yearbook in 2017. According to its website, the “cork” in the title refers to “an unprepared student who was called upon in class but who remained silent, like a corked-up bottle.” “Curl,” meanwhile, describes “a student who performed well in class and who, when patted on his head by his professor, ‘curleth his tail for delight thereat.'”

About cork and shoe polish

Cork isn’t the only unlikely makeup tool associated with black face. Greasepaint, and even shoe polish, have been used for nearly two centuries to darken a white person’s skin in mockery of a black one.

Shoe polish was young Northam’s means of choice. In fact, he seems to be somewhat of a connoisseur, explaining in a press conference that “the reason I used a very little bit is because, I don’t know if anybody has ever tried that, but you cannot get shoe polish off.”