Populism revisited: expect more twists and turns ahead

Global economies have continued to improve, with unemployment rates in many economies at multi-decade lows. But the attraction of populist candidates persists despite this progress.

Global economies have continued to improve, with unemployment rates in many economies at multi-decade lows. But the attraction of populist candidates persists despite this progress.

Candidates or parties who paint debates in simple choices—“us” vs “them” and “the people” vs “the corrupt elites”—are taking a bigger share of the popular vote. These groups push similar agendas that are anti-establishment, authoritarian, and nativist. Across Europe, these trends have been underway since the early 1990s.

It’s not surprising that populists are now in charge in Italy, given how the Italian economy has performed under the European Monetary Union. But even in Germany, recent state electoral results showed a further weakening of the political center in favor of both the left and right extremes.

Abandoning the center is picking up across emerging countries too, with populists elected to head Latin America’s two largest economies in 2018. Andrés Manuel López Obrador, from the left side of the political spectrum, was elected in Mexico last July. From the right, Jair Bolsonaro was elected in Brazil last October. Both rode waves of popular disillusion with mainstream politics.

Meanwhile, the Brexit saga continues and the US midterm elections fell short of the “blue wave” revolt that some had expected. It seems safe to say that concerns are only increasing about what the populist urge might bring next.

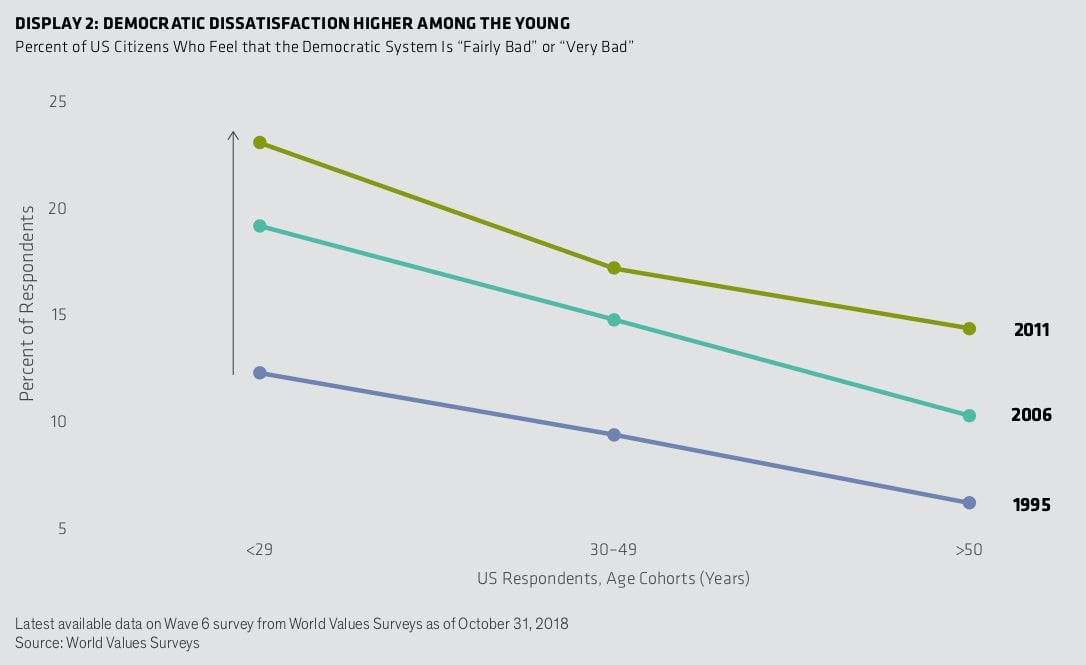

There are deep-seated causes for this shift in global political dynamics. Income and wealth inequality has been widening since the early 1980s. Forces from globalization, technological change, and other factors are increasing the stresses from high debt levels and aging populations. These trends are driving the sense that current political institutions aren’t delivering—a sense that’s heightened among younger generations.

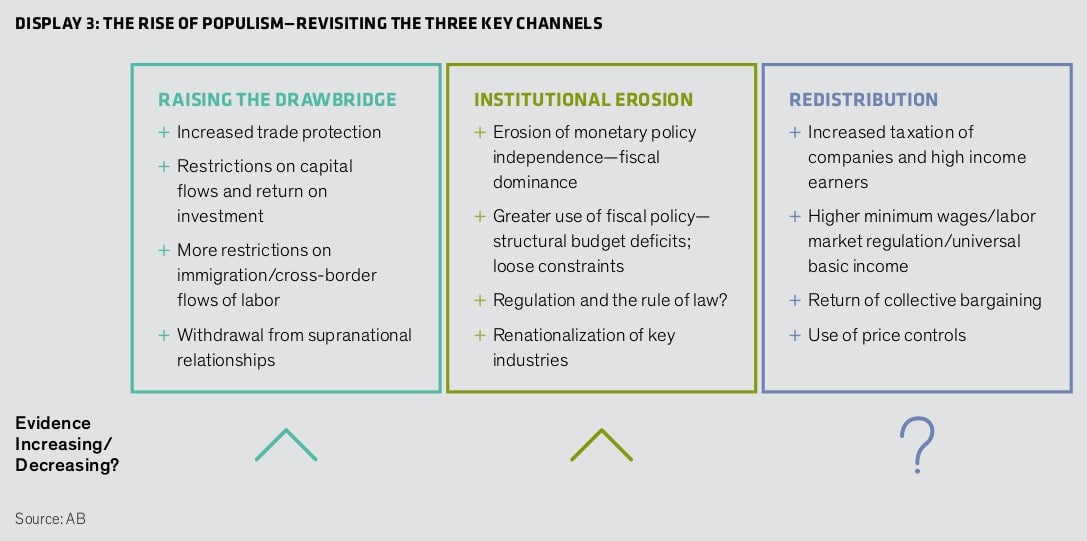

The bottom line is that populist forces are here to stay. But how effectively have these political forces been channeled into actions that will impact economies and markets? You can expect policy changes in three broad channels: raising the drawbridge, institutional erosion, and redistribution.

Raising the drawbridge

There’s significant evidence of policy advances in raising the drawbridge—where policies become more national and less global. These include restrictions on trade, labor, and capital flows.

Examples include the ongoing trade conflict between the US and its partners, including China, Canada, and Mexico. There are also the withdrawals from multinational arrangements, such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership and the Paris Climate Accord. Anti-Brexit and anti-Brussels sentiment apply here too.

Institutional erosion

The second channel, institutional erosion, includes measures that undermine constraints on political behavior or threaten the independence of central institutions, like the media and the judiciary. Attacks on institutions can also attempt to dismiss financing constraints in fiscal policy and weaken central bank independence.

In the last couple of years, there have been many attacks on media independence, from President Trump’s complaints about fake news in the US to the closure or limiting of media outlets in Hungary and Turkey. Fiscal policy constraints are also being ignored—notably in the US, but also in Europe through Italy’s budget proposals.

The days of independent central banks may be numbered as well, from open criticism of the Fed to Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan stating that his patience on central bank policy “has limits.” The dispute between India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Governor Urjit Patel over the Reserve Bank of India’s independence is another example among many.

Redistribution

There’s less evidence of policy action in the third channel, redistribution—where we’d expect to see efforts to transfer wealth from one group to another, often through the budgetary process. This could include initiatives to shift wealth from the “rich” to the “poor,” from the “elites” to the “people,” or from “corporations” to the “workers.”

National income has been shifting away from labor for quite some time. The increased globalization, technological disruption, and institutional change have compressed living standards for workers at the middle to bottom end of income distribution and bolstered corporate profits. But the corporate sector hasn’t yet been a lightning rod for populist anger in the way that China, free trade, or “the Washington swamp” have.

Yes, there have been some efforts to raise minimum wages—like South Korean President Moon Jae-in’s minimum wage hikes of 16% in 2018 and 10% in 2019. But we haven’t seen broader attempts to shift the balance of bargaining power from capital back toward labor—at least not yet.

What to expect in upcoming policies

The idea of becoming less global and more national will probably continue—whether through trade disputes, arguments over who pays for NATO, the Brexit divorce, or a broader European backlash against Brussels.

It’s likely that more erosion of institutions will be reflected in economic policy challenges. One of the easiest ways to cope with public sector finances that are bloated by debt is for governments to lean on central banks to keep things moving.

Populist policies could target the corporate sector in two ways. We could see a return to the sort of competitive, or antitrust, policies that ruled before the 1980s—policies that made many industries concentrated with a handful of firms, or sometimes one, dominating.

The second avenue could be through more explicit initiatives to shift the balance of power toward labor, like for example the UK Labour Party’s manifesto that includes a four-day work week, mandatory employee representation on boards, and a bigger role for unions in collective bargaining. As a group, these measures would shift policy from decades of being business friendly to a decidedly labor-friendly tone.

The macro impact

The bottom line is that we shouldn’t expect a return to the policymaking orthodoxy of the decades that led up to the global financial crisis. More populist-inspired initiatives through the three main channels—raising the drawbridge, institutional erosion, and redistribution—are likely.

Together, these policies are likely to shift potential macro outcomes in a more challenging direction. Even if nominal income growth stayed the same, the mix would surely change, and we could see higher inflation, lower economic growth rates, and more pressure on corporate profit margins.