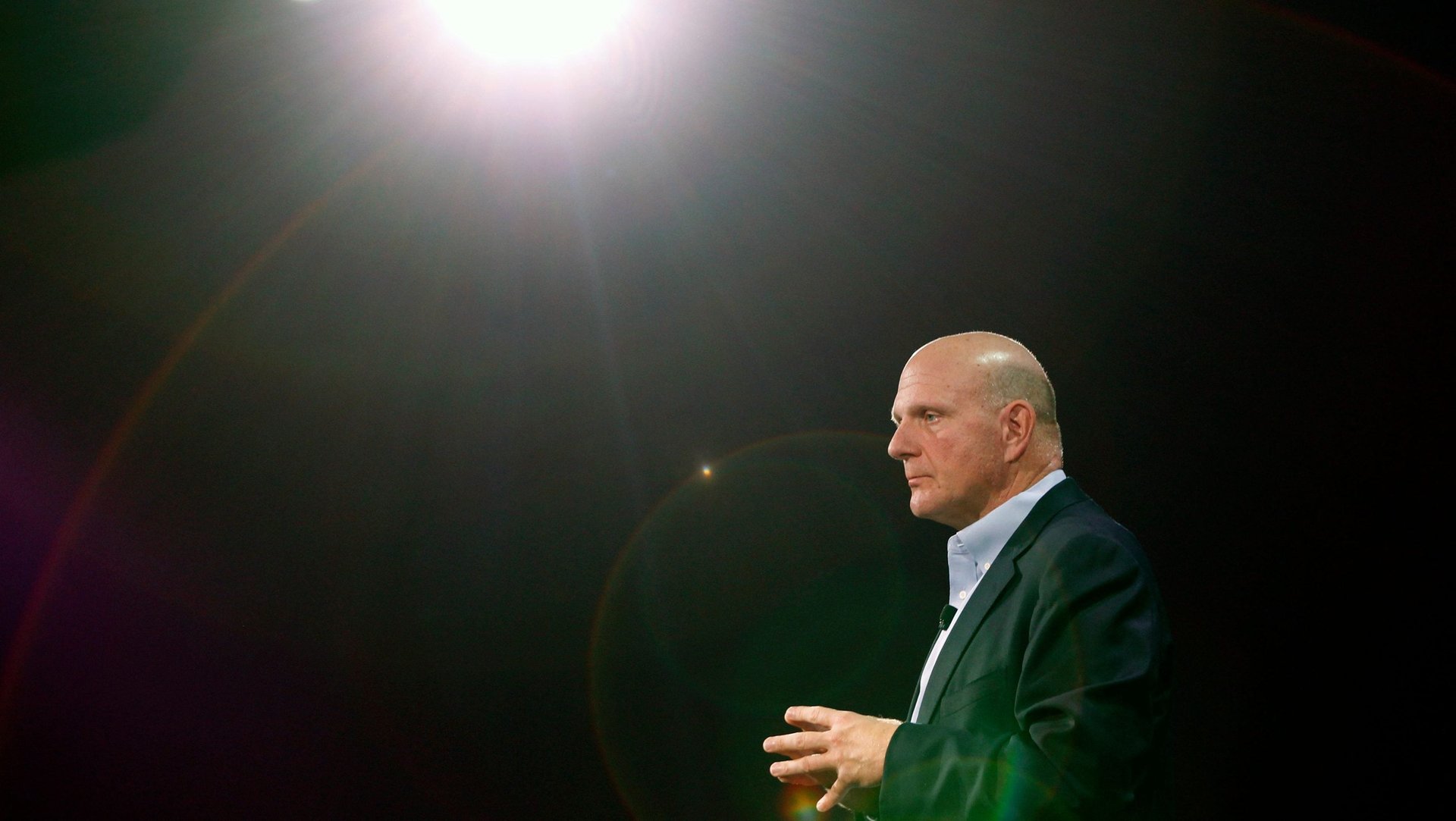

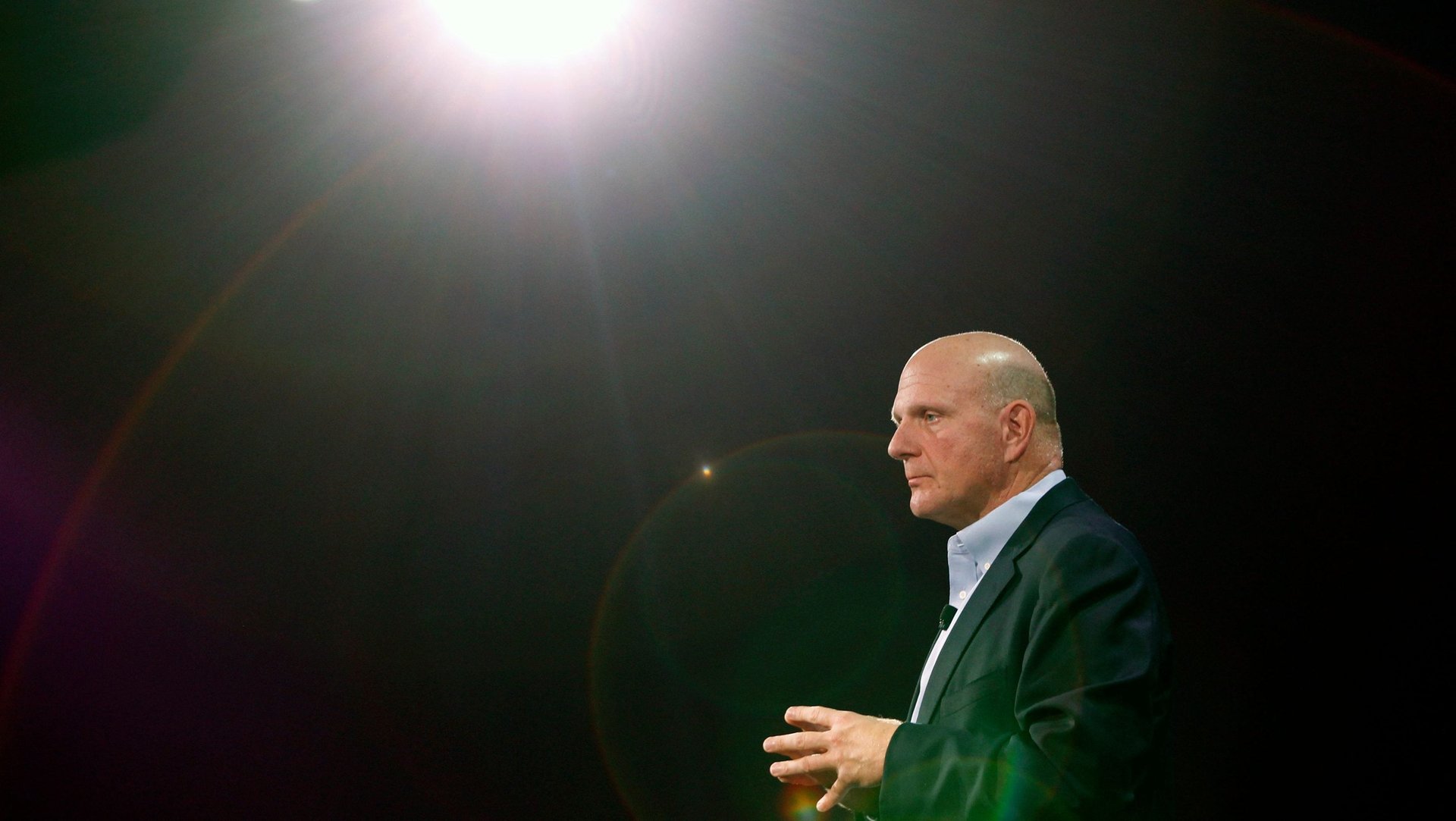

Steve Ballmer played a powerful part in Microsoft’s comeback

Former Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer did not leave the company on a high note.

Former Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer did not leave the company on a high note.

Ballmer held the role from 2000 to 2013, while Microsoft tried again and again to convert its software dominance into a viable hardware business, similar to the way Apple had leveraged the iPod and iTunes to own the MP3 player category. It objectively did not go well. The Zune, an iPod competitor that the author personally loved but was plagued by horrific software and an extremely useless online music store never lived up to the iPod’s legacy. The Kin, a very round iPhone competitor, lasted on the market for less than two months. The Windows phones all flopped, in a multibillion-dollar loss for the company. Windows Vista—Microsoft’s attempt at refreshing its operating system in the era of the internet—was widely panned, and Ballmer fought tooth and nail to extend the business model of selling Windows licenses, rather than embracing the cloud strategy that would be installed by his successor.

When Ballmer told the Microsoft board he was stepping down in 2013, according to one report directors quickly agreed (pdf) that “fresh eyes and ears might accelerate what we’re trying to do here.” The company’s market capitalization hadn’t moved much since Ballmer had became CEO more than a decade earlier. Meanwhile, competitors Amazon and Google had started growing into the behemoths they are today.

The media has not been kind to Ballmer. There are listicles with titles like, “Steve Ballmer’s Biggest Mistakes As CEO Of Microsoft.” Vanity Fair described his tenure in a headline as “Microsoft’s Lost Decade.” The New Yorker had a particularly blunt story on the day Ballmer stepped down as CEO, titled “Why Steve Ballmer Failed.” Here’s a taste:

Ballmer is roughly the tech industry’s equivalent of Mikhail Gorbachev, without the coup and the tanks and Red Square. When he took control, in 2000, Microsoft was one of the most powerful and feared companies in the world. It had a market capitalization of around five hundred billion dollars, the highest of any company on earth. Developers referred to it as an “evil empire.” As he leaves, it’s a sprawling shadow.

These assessments are supported by plenty of well-worn examples of Ballmer’s retrospective missteps. But they overlook Ballmer’s undeniable positive contribution to Microsoft’s current success—that even as Ballmer fought (too hard, in retrospect) to keep Windows as the crown jewel of Microsoft, he was also responsible for laying the groundwork that makes Microsoft the new company it is today.

Current Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella is rightly given credit for focusing Microsoft on moving its legion of products to the cloud and working with partners to use more and more cloud capabilities. Yet it was Ballmer who originally created Azure, named Windows Azure when it launched in 2010.

“For the cloud, we’re all in,” Ballmer said at a 2010 keynote, according to Network World. “Literally, I will tell you we are betting our company on it.”

Nadella was actually installed by Ballmer to lead the creation of that business, in the role of president of Server and Tools.

“A lot of the seeds that Ballmer started, like Azure, were the right kind of strategy moves,” says Brent Bracelin, equity research analyst at KeyBanc Capital Markets. “I think where Satya has really differentiated is empowering the employee base to go execute on some of that early kind of strategy, kind of seed planting that Ballmer did.”

Even before launching Azure, in 2001 Ballmer acquired Great Plains, a company that made a business management software called Dynamics. Nearly 20 years later, Microsoft still uses the Dynamics name, though the product has evolved into a cloud service for accounting, enterprise resource management, and customer relationship management. Dynamics 365 is now one of Microsoft’s top cloud earners. While the company does not break out Dynamics revenue in its earnings, the product was categorized by executives as a billion-dollar business in 2013 and has seen consistent revenue growth year over year since then.

Yes, it could have theoretically been an even better business. While today Dynamics is a flagship business product for Microsoft, Salesforce was founded in 1999 and enjoys $120 billion in market capitalization. It’s unlikely that Marc Benioff could have convinced top brass at Microsoft to deviate from their lucrative licensing business to cloud services so early, and Salesforce’s $1.1 billion tower in SF stands as a testament to the money Microsoft missed out on not dominating the business tools market.

But as Bracelin says, Satya’s strength has been refocusing the company around the myriad long-term bets that Ballmer had set up.

“That cloud-first mantra is really something that you can give ownership to Satya, even though some of these strategies and products were under started under the Ballmer era,” he said.

It’s easy to make fun of Ballmer—for his business decisions, his mannerisms, his sweat— but the predominant narrative is too simplistic. Ballmer missed the boat on search, mobile, and media, but he set the stage for Microsoft as it stands today: something that could evolve into something larger and more fundamental than all three.