This man was just evicted from Beijing’s underground heating system—and there are many more like him

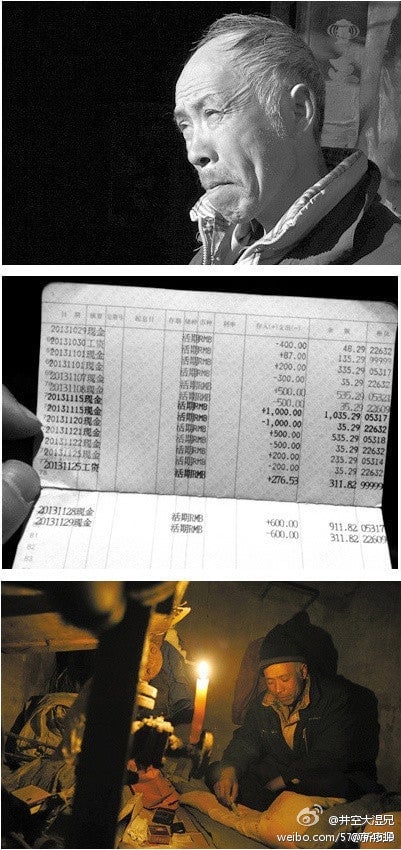

In a luxury residential neighborhood in northeastern Beijing, a 52-year-old man named Wang Xiuqing has been living in the underground pipelines (link in Chinese) of the city’s heating system for 10 years.

In a luxury residential neighborhood in northeastern Beijing, a 52-year-old man named Wang Xiuqing has been living in the underground pipelines (link in Chinese) of the city’s heating system for 10 years.

On Dec. 6, after seeing news reports (Chinese) of Wang and others’ underground abodes, officials removed the residents and sealed off the manholes leading to their makeshift homes with concrete. As a result, Wang and a few others have quickly become the focus of an outpouring of sympathy and anger on Chinese social media (registration required) over the treatment of the city’s many migrant workers.

Because of Beijing’s sky-high apartment rental costs, as many as two million people—about a tenth of the city’s population—are said to be living below street level in underground storage basements and air-raid shelters partitioned into cramped, windowless rooms. Many of those who have to crowd into these homes are migrant workers like Wang, from the nearby province of Hebei. Because of a household registration system that connects them with their hometowns, they’re often barred from using public services like education and healthcare.

On Sina Weibo, the country’s largest microblogging site, photos of Wang’s filthy bedroom and details of his story circulated under the hashtag “well-dwelling snail house,” using a common phrase to describe humble, tiny homes. Wang earned his keep by washing taxis and collecting plastic bottles for recycling, and used the pipes in his underground tunnel to keep warm. By Dec. 9, the hashtag had over 45,000 comments.

The comments ranged from offers to help the residents find jobs, to criticism of officials for sealing off their homes. “Is this how they provide assistance to homeless people?” one user said. Others criticized the pace of the country’s problems with income inequality. “This problem roots deeply in the yawning wealth gap rather than illegally residing in the well. The government’s solution is crude and brutal,” another said.

The attention may be helping. According to Xinhua, Wang has been offered a job at a college in Beijing that should pay between 3,000 and 4,000 yuan (link in Chinese), between $490 and $650 a month —about a 1,000 to 2,000 yuan more than what he was previously earning. The debate could also further motivate Beijing city officials who have said that providing more affordable housing in the city is a top priority. Authorities say they will supply 20,000 cheaper homes (paywall) for “self use”—for residents to live in, not hold for investment, which drives up prices.