Trump has appointed the highest percentage of inexperienced ambassadors since FDR

Donald Trump has selected ambassadors who are less qualified than any appointed since the administration of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, according to a new study of previously unavailable government documents.

Donald Trump has selected ambassadors who are less qualified than any appointed since the administration of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, according to a new study of previously unavailable government documents.

“In short, it appears that campaign contributions may be generating an increasingly deleterious effect on the quality of U.S. diplomatic representation overseas,” writes Ryan Scoville, a law professor at Marquette University who conducted the study.

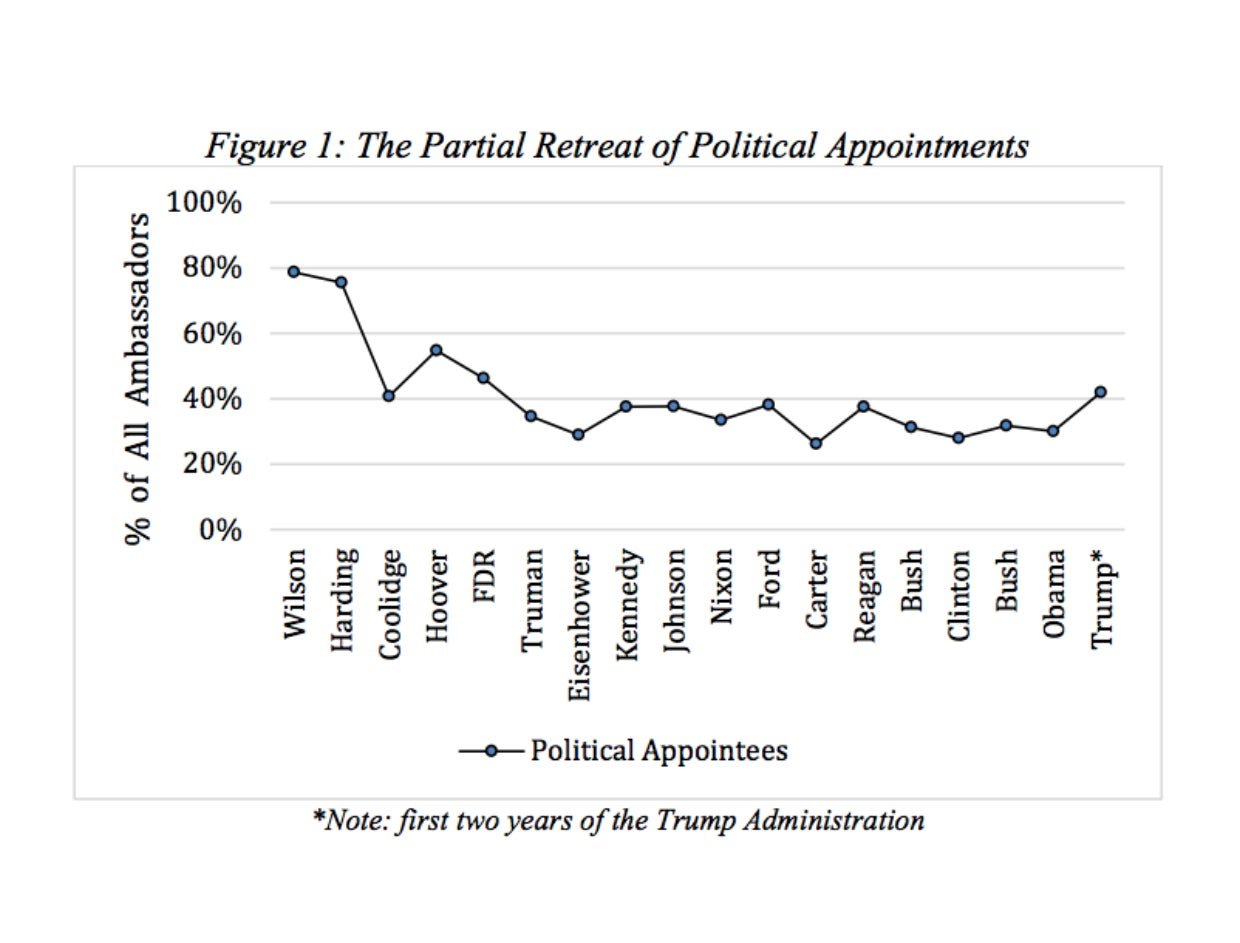

Scoville spent four years prying loose State Department records under the Freedom of Information Act, revealing the qualifications and political contributions of more than 1,900 ambassadorial nominees going back to the Reagan administration. During Trump’s first two years as president, 42% of his picks have been political appointees with no diplomatic experience, the highest figure of amateur US diplomats serving since Roosevelt’s tenure (46%) and a significant rise from the 30% recorded under Barack Obama.

Scoville said the data he received shows the qualifications of the typical nominee have deteriorated since 1980. Further, the average campaign contribution from political nominees grew significantly over the past 40 years, even after adjusting for inflation.

“Viewing these two developments together, I can’t help but wonder whether the ballooning cost of presidential elections is steadily placing greater pressure on recent presidents to pay more attention contributions and less attention to qualifications in selecting among prospective nominees,” Scoville tells Quartz. “If that’s what’s happening, and if qualifications predict performance in office, then the imperatives of campaign finance are indirectly degrading the quality of US representation overseas. This strikes me as a real concern.”

Unqualified to deal with a dangerous world

The world is becoming an increasingly dangerous place and if the US hopes to maintain its global influence, it can’t afford to appoint “under-qualified or incompetent” diplomats to important postings, Scoville’s paper, published this week in the Duke Law Journal, states.

It is not uncommon for newly elected presidents to nominate fairly large numbers of non-career diplomats, Scoville writes. If the trend holds with Trump, the percentage will drop in the coming years of his term and the ratio could conceivably fall in line with historical norms.

“On the other hand,” Scoville continues, “president Trump appears unusually hostile toward the Foreign Service, viewing many of its officers as part of a ‘deep state’ that works to thwart his initiatives.”

Whether a nominee is prepared for an ambassadorship depends upon factors including language ability, regional knowledge, and foreign-policy experience. Some less-empirical traits are also important—negotiation skills, work ethic, and likability, Scoville says. The records he obtained suggest that “there have been many nominees who don’t check any boxes. This has been true at least since Reagan, but I think it’s particularly common now.”

More than half of the first 15 ambassadors appointed by Trump have been financial backers. Among them: New York Jets owner Woody Johnson, who donated $1 million to Trump’s inaugural committee and is now ambassador to Great Britain. Several members of Trump’s various private clubs have been rewarded with ambassadorships including handbag designer Lana Marks, New York City businessman David Cornstein, and Robin Bernstein, a charter member of Trump’s Mar-a-Lago resort in Palm Beach and former insurance broker nominated to be ambassador to the Dominican Republic in 2017.

David Friedman, a bankruptcy lawyer by trade and Trump’s ambassador to Israel, was criticized by five former US ambassadors to Israel as unqualified and described as someone who takes “extreme, radical positions.” Callista Gingrich, wife of former House speaker Newt Gingrich and Trump’s ambassador to the Holy See, was called “extraordinarily unqualified” by the Rev. Gerald Fogarty, a Jesuit who is a professor of religious studies and history at the University of Virginia.

“Celebrities may thrill part of the population, but host governments do not want to discuss complicated, important issues with a neophyte, especially one representing a superpower,” former career foreign service officer Edward Peck has said. “To put it bluntly, sending a beginner with no connection to the host country instead of a trained diplomatic professional is correctly seen as demeaning.”

It happened before Trump

Ambassadors are vetted by the Presidential Personnel Office (PPO), where the staff turns over with each new administration. “It’s an office that, for lack of a better way of describing it, is a presidential patronage office,” Brett Bruen, a former US diplomat who was director of global engagement in the Obama White House, tells Quartz. “A place where the spoils of the campaign can be handed out.”

A 2018 Washington Post investigation found that under Trump, the PPO has been largely staffed by inexperienced former campaign workers in their 20s who turned the office into a “social hub” where people could be found sitting on couches vaping, past and present White House officials said.

The PPO “requires a lot more oversight than it’s currently getting,” Bruen contends. The president “can and should have the prerogative to choose who he or she wants” for appointed positions but there needs to be a mechanism that allows for other options in consideration of national security concerns, Bruen says.

There’s plenty of precedent for Trump’s nominations. George W. Bush gave ambassadorships to at least five campaign donors; his father, George H.W. Bush, nominated Joy Silverman, a financial backer without diplomatic experience, a college degree, or any perceptible work history to be his ambassador to Barbados. In 1981, Ronald Reagan appointed John Gavin, a personal friend, as the US ambassador to Mexico. However, Gavin, an actor who played Julius Caesar in Stanley Kubrick’s “Spartacus,” spoke Spanish, spent two years as president of the Screen Actors Guild, and served as a special adviser to the secretary general of the Organization of American States during the 1960s and early ’70s.

The Obama administration “was certainly not immune from these kinds of political choices,” Bruen says. George Tsunis, a real-estate executive and major Democratic fundraiser nominated by Obama to be ambassador to Norway despite never having been there, flubbed a confirmation hearing in which former Minnesota senator Al Franken said he “displayed a tremendous amount of ignorance.”

But Bruen warns against painting all political ambassadorial appointees with the same brush. Colleen Bell, a television producer who worked on the daytime soap opera The Bold and the Beautiful, was Obama’s ambassador to Hungary. Bruen says she was in fact a very good diplomat. And James Costos, an HBO executive before becoming Obama’s ambassador to Spain, was “one of the most dynamic, really exceptional diplomats that I’ve worked with,” Bruen says. “He’s a Hollywood executive but he understood diplomacy, had experience working overseas, and brought that to the position.”

Can the system be fixed?

According to Scoville, some say the Constitution gives the president “exclusive and formally unlimited discretion over nominations.” However, he writes that it in fact “leaves room for several types of legislative intervention,” including requiring that appointees meet “reasonable qualifications requirements by statute.”

“Popular debates about the merits of appointing donors to ambassadorships have occurred for decades, and yet the practice persists,” says Scoville. “Part of the problem is that a lot of the nominees have also contributed to the election campaigns of members of the House and Senate, the effect of which is to create a disincentive for reform on the part of Congress. The Democratic House seems more activist than its immediate predecessor on matters of foreign policy oversight and legislation, so it’s plausible that it would embrace new reforms to regulate qualifications. But I’m skeptical the Senate would go along.”