Ukraine is having more trouble keeping cash in the country than protestors off the streets

For Ukraine’s beleaguered government, what’s happening in the capital markets is every bit as threatening as the throngs of protestors in Kiev’s central square. President Viktor Yanukovych’s government has already survived a no-confidence vote thanks to strong support from the Russian-speaking east of the country. No such support is on offer in the markets, where nervous investors are punishing Ukrainian assets as popular unrest continues to roil the country.

For Ukraine’s beleaguered government, what’s happening in the capital markets is every bit as threatening as the throngs of protestors in Kiev’s central square. President Viktor Yanukovych’s government has already survived a no-confidence vote thanks to strong support from the Russian-speaking east of the country. No such support is on offer in the markets, where nervous investors are punishing Ukrainian assets as popular unrest continues to roil the country.

Credit-default swaps—a form of insurance that pays out if a bond defaults—blew up for Ukrainian government bonds recently, with spreads that now suggest the country is twice as likely to default as Greece. Only Venezuela and Argentina are considered riskier borrowers, according to this measure.

This is thanks in large part to Ukraine’s dwindling foreign reserves. Ukraine imports far more than it exports, and around half of government debt is denominated in foreign currencies (mostly dollars). This means that the country needs a lot of dollars, euros and the like to pay for imports and interest on its debt. This puts downward pressure on the local currency, the hryvnia. To counteract the fall, Ukraine’s central bank has been selling down its stock of dollars. There are now only enough reserves to cover around two months of imports.

To keep reserves at current levels, analysts at Morgan Stanley reckon that Ukraine needs to raise around $14 billion between now and the next presidential election in March 2015. This will be increasingly difficult as bond investors push the country’s borrowing costs higher.

Reserves are also threatened by the country’s savers swapping out their hryvnia deposits for dollars. A dash for dollars was seen during the country’s last bout of popular unrest, in 2004, and following the global financial crisis in 2008. In both cases, the central bank’s foreign reserves were two to three times larger in relation to bank deposits than they are today, according to analysts at UkrSibbank (pdf).

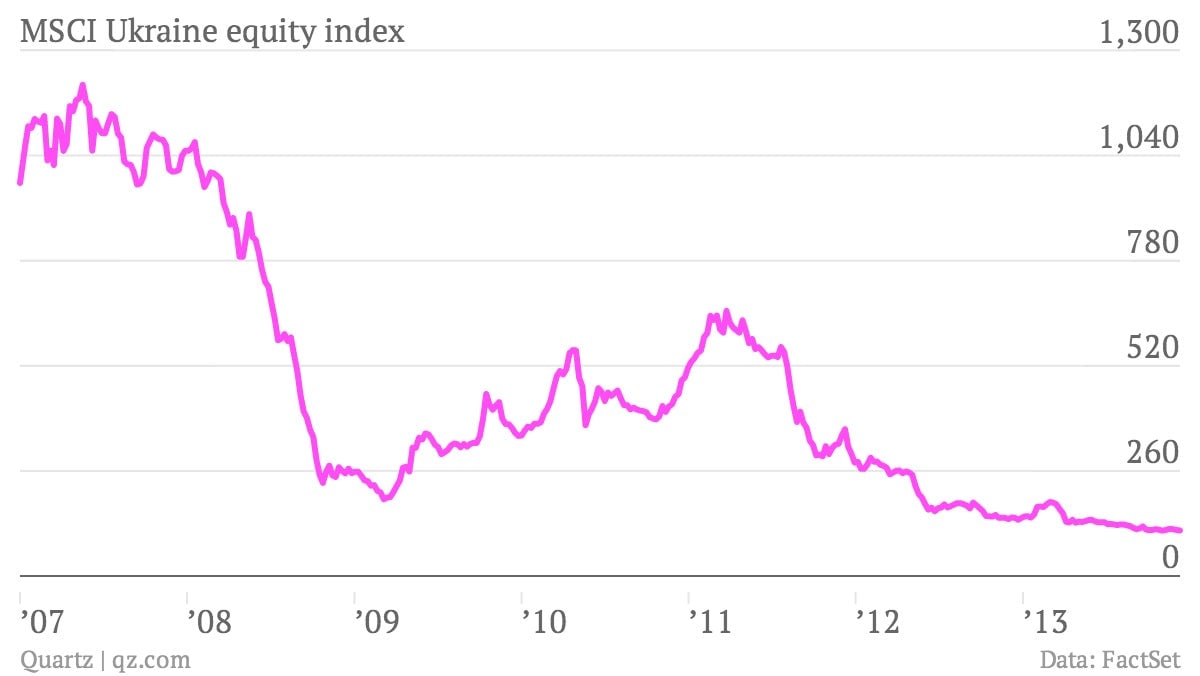

In a clear sign of the stress on the country’s banking system, overnight interbank lending rates have soared to 20%, signaling a potential shortage of cash. In 2004 and 2008 Ukrainian authorities imposed restrictions on deposit withdrawals to prop up the hryvnia. This isn’t the case this time around—at least, not yet—but the financial turmoil is clearly hitting Ukrainian companies, with stocks plumbing new depths each day:

The Ukrainian government’s decision to push for closer ties with Russia instead of the EU kicked off the unrest, so the markets will be watching closely for details of the deals on offer from Moscow. A huge share of Ukraine’s imports is gas piped in from Russia, so any relief on the price Ukraine pays, or on the bills it already owes, will relieve the pressure on the country’s finances. For all of the trouble Ukraine’s leaders are having pushing protesters out of central Kiev, they face an even bigger challenge convincing local savers and foreign investors to keep their cash inside the country.