How to fix Obamacare: Listen to doctors

As a doctor, I have been struck watching CNN by the many perspectives on the Affordable Care Act, better known as Obamacare. There are stories about customers’ sticker shock at plans with deductibles as high as $12,700 for families. There are stories on US president Barack Obama criticizing the insurance companies for having substandard plans. And there are stories about people blaming the president after losing their current insurance.

As a doctor, I have been struck watching CNN by the many perspectives on the Affordable Care Act, better known as Obamacare. There are stories about customers’ sticker shock at plans with deductibles as high as $12,700 for families. There are stories on US president Barack Obama criticizing the insurance companies for having substandard plans. And there are stories about people blaming the president after losing their current insurance.

Yet in none of these were doctors even mentioned. It’s as if doctors do not know the intricacies of the health-care system. As if doctors are not there for their patients 24 hours a day. As if doctors are not dealing with denials from the insurance companies on a daily basis, losing valuable hours to menial paperwork.

Doctors have a duty to care for their patients and are the engines that put health care into motion. Unfortunately, doctors’ voices are largely excluded from the discussion of health-care reform. Their valuable insight into the day-to-day operations of this health-care machine is ignored. This strikes me as misguided. Would you want to build a plane with no input from a pilot? Or design a curriculum without a teacher’s input? These insider insights are essential. Unless we look to doctors to help solve these dilemmas, we will be doomed to spiraling costs, dysfunctional insurance companies, and, of course, more talking heads on TV blaming others.

A doctor’s view on what’s wrong with Obamacare

The new system being implemented under Obamacare will ultimately lead to sicker patients and low-quality care for three reasons:

1. Older doctors will retire early, fed up with the system. These older doctors mourn the loss of the patient-physician relationship. The burdensome paperwork chokes their ability to provide good care. Additionally, even as doctor expenses increase under the new regulations, projected cuts in reimbursement of up to 26% threatens doctors’ livelihoods. These cuts could force doctors to stop seeing Medicare patients because the expense of treating them is exceeding the reimbursement, which has already declined steadily over the past several years.

2. Smart young people will no longer enter the field of medicine due to rising debt (which averages more than $200,000 after medical school) and severe cuts in reimbursement. If young college students realize that they cannot provide for a family despite going to school and training for a total of 14 years, they will turn to different professions.

3. Today’s younger doctors will become more demoralized by lawmakers dictating how they provide care. They are increasingly being treated as machines, expected to answer patient calls at 2am, work 24-hour shifts, do more procedures for less, and fill out a growing mountain of paperwork. And they’re expected to do all this while the threat of getting sued for any mistake hangs over them. This will produce a high burnout rate and poor care.

Unfortunately, with all the unnecessary documentation and regulation, doctors are losing the bond with their patients that is so critical for high-quality care. For those doctors who choose to stay in the field, many of them will instead elect to practice direct-pay or “concierge” medicine, taking the insurance company out of the equation. This will create a massive shortage of doctors and threaten the health of our citizens.

Here’s what the doctor orders

As a doctor, I do not want this to happen. I consider medicine a calling and went into this field to help others and take this role seriously. To help patients and address their health needs, I expect to have time to sit down and talk with my patients, to share stories with them—without watching the clock, and without administrators or computers documenting every move I make.

I—and other doctors—are also concerned with the equality issues that lawmakers raise. We too want every person in America to have access to quality health care at a reasonable price. But that elusive goal cannot materialize unless lawmakers look to those of us on the front lines of care for input. We know why costs are high, and we can help inform the public about how it all works. But we need a representative sample of practicing doctors advising Congress on these issues.

Here are my ideas for better and more affordable care:

Costs and reimbursement must be simple and transparent.

Lawmakers and the media need to stop attacking doctors for how much they earn and perpetuating misconceptions.

A recent New York Times headline announced: “As Hospital Prices Soar, a Stitch Costs $500.” But these inflated numbers have nothing to do with what the doctor actually gets paid. In fact, those bills do not go to the doctor at all, but rather to the hospital. When a hospital or doctor submits a bill, the insurance companies or Medicare/Medicaid use a fee schedule to determine the payment. This is often called the “allowable charge” on patients’ bills.

To complicate matters, there are usually two different charges in a patient’s bill: a “professional” charge from the doctor, and a “facility or hospital” charge. The doctor does not collect any of the hospital charge, and receives only a small fraction of the professional charge because these allowable payments do not include overhead expenses for the practice, which can range from 30% to 60%.

It’s understandable that this is confusing to patients. Other professionals get paid what their bill says. If a handyman comes to fix your sink and charges $80, you pay him $80. If your lawyer says he charges $250 an hour and he works four hours for you, you owe him $1,000. Unfortunately, medical billing is much more confusing.

Even our leaders, who should know better, seem to misunderstand this. In this video of Obama discussing foot amputations caused by diabetes, the president claims that surgeons get paid “30, 40, 50 thousand dollars” for a foot amputation. Looking at the Medicare Fee schedule, however, the code states that the surgeon would get paid $738.90. This $738.90 needs to cover his office space, staffing, medical liability, and years of training necessary to perform this life-saving operation. Our leaders are clearly confused.

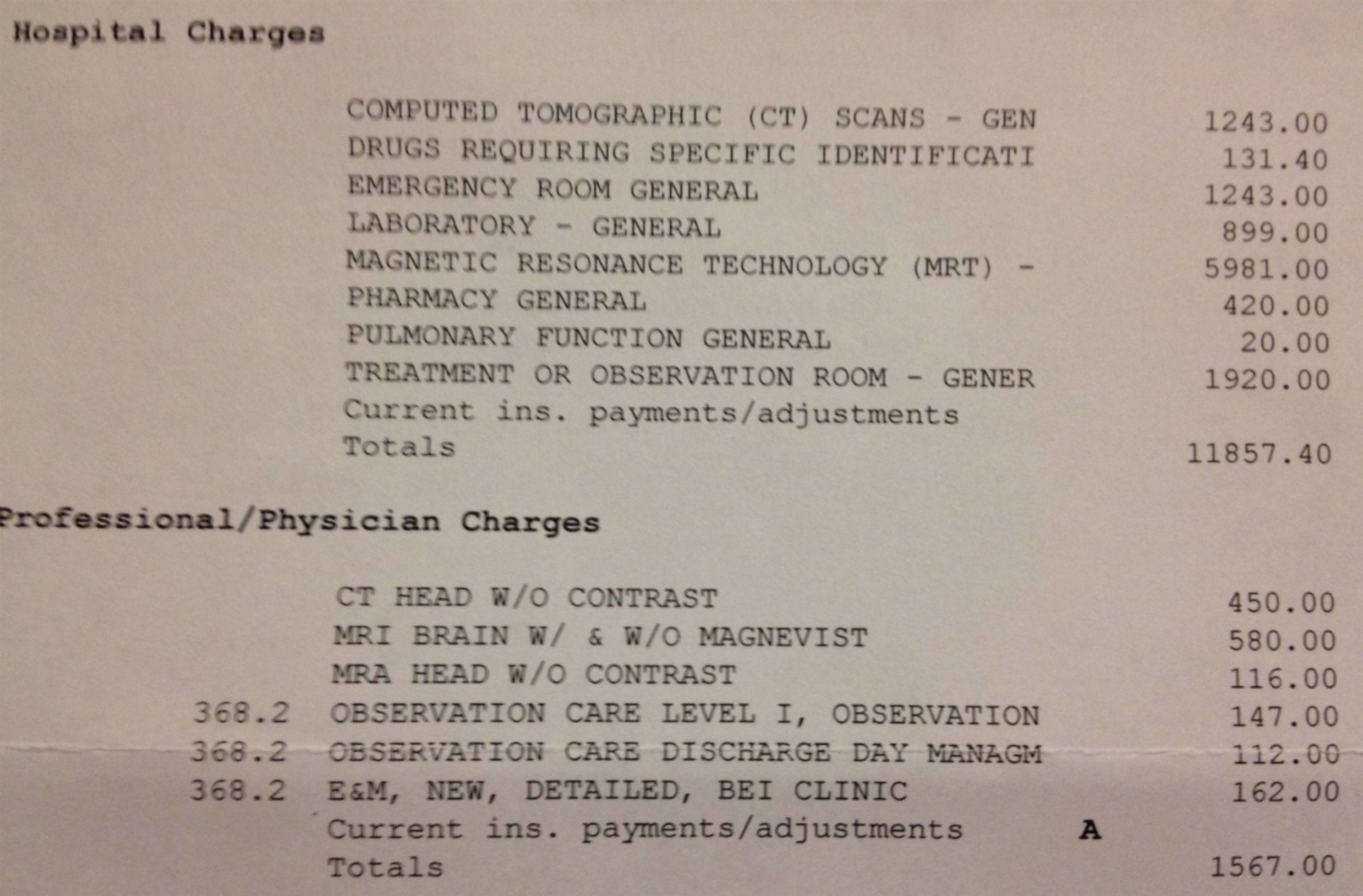

Another example of confusing costs of medical treatment hits closer to home as my own mother presented to the ER with sudden blurry vision a few weeks ago. Concerned for serious causes for this symptom, several tests were run to rule out causes such as stroke or tumor. Thankfully, her diagnosis was nothing life threatening and she is recovering. She then received the following bill two weeks later in the mail explaining her charges. A copy of the bill appears below:

She was shocked at how high the charges were and could not decipher this bill. Referring to the explanations above, under “professional/physician charges”, it appears a physician gets paid $450 to interpret a CT head and $580 to interpret an MRI of the brain. This is far from the truth. Looking at the fee schedule, code 70450, a CT head would pay a doctor $29 for a Medicare patient—far lower than the $450 shown on the bill. In fact, it is only 6% of what the bill states! Likewise, an MRI brain, code 70558, would pay a radiologist $109—a way off from the charge of $580. There are other inflated fees for the hospital as you can see in this bill totaling over $11,000, but these are not related to a doctor’s compensation. This clearly illustrates that doctors’ payment systems are confusing for patients and create much anxiety when trying to decipher a bill in the mail.

It is apparently even confusing to lawmakers and the president who are trying to modify reimbursement yet do not know how doctors get paid. Even though a stitch may cost $500, the doctor got paid $28 dollars to read a complex CT scan of the brain. We need real costs to health care, not inflated charges from hospitals. This needs to be addressed so patients and lawmakers can understand where doctors are coming from and realize that doctors are getting paid much less than meets the eye.

The fee schedule strangles doctors’ flexibility by ordaining flat-rate payments no matter what the circumstance. Doctors are not paid extra for talking on the phone to patients or other doctors, writing prescriptions, ordering lab work or radiology tests. If we drive to the hospital in the middle of the night to perform a procedure, the payment is the same as a scheduled operation during office hours. If one procedure takes longer than average or is more complex, a doctor does not collect any additional payment.

Do I speak with patients in the evening, or spend the extra 30 minutes to help patients get the quality care they deserve? Of course. I willingly do this, because I went into medicine to help those in need. I do worry, however, that this may become impossible for some doctors if reimbursement models are not modified and doctors’ fees not corrected for inflation and overhead expenses.

The solution is to make costs and charges more transparent, so that patients can see the true (not inflated) costs and benefits of medical devices, services, and materials. If patients know the real costs of their health care, they will be able to make educated choices. It would also increase competition among providers, which would lower prices and offer patients more options.

The next necessary step is to enact tort reform.

Doctors’ first goal is to help patients. But we all are human, and mistakes will happen. Patients who are injured by mistakes must be compensated in accordance with the law, but the current system is broken. With no set standards, decisions on malpractice suits vary widely, jury to jury. This unreliability leads to defensive medicine, where doctors order tests and procedures just to prove that they did something, or they excessively document trivial facts to prove they looked at everything. Gallup estimates that a quarter of all health care dollars are spent on defensive medicine—about $650 billion per year.

Here is a typical example of defensive medicine: If a family physician deduces that a patient’s headache is likely due to tension and there are no warning signs for a more serious condition, the doctor would probably not, under normal circumstances, order a CT scan, and instead would just have the patient follow up if symptoms persisted. But in rare cases, such a headache could be caused by a tumor or bleeding in the brain. In such a rare case, the patient could sue the doctor for not ordering the CT scan earlier. Knowing this, a doctor practicing defensive medicine would order scans with only the slightest justification—simply to avoid a frivolous lawsuit. This concern interferes with the doctor’s ability to use her knowledge and training to determine the nature of a patient’s ailment, or the best treatment for it.

The patient also loses under the current tort system. In fact, the only winners are the lawyers. Thirty-nine percent of cases take three years to settle and 60 cents on the dollar are used for lawyer fees and administrative costs. Patients should be compensated when they experience poor health care, but this current system fails them, as well as doctors.

The answer to this rests in the health care courts described by Common Good chair Philip K. Howard. He suggests that expert judges—without juries—should determine what is good versus bad care. Health care courts would allow judges to dispose of weak and invalid claims quickly after filing, while also discouraging doctors and insurers from fighting cases in which they are clearly at fault. They would provide consistent standards for various health care situations. They would let us doctors do our jobs without lawyers looking over our shoulder. And they would provide patients with fair, consistent rulings when they are wronged.

Use health savings accounts to increase patients’ roles in their own health

.

Patients could use pre-tax dollars, contributions made by employers, and in some cases a government subsidy to fund the accounts. With actual money in the accounts, patients would be able to better plan their health care spending, and to use this money as if they were consuming any other good or service. This money could grow each year, like an investment account and even be passed on to heirs after death.

As discussed above, for these accounts to work, hospitals’ and doctors’ prices must be more transparent and reflect true costs, so that patients know what they are buying. Under the current system, a patient with a knee injury has no reason to question it when a doctor orders an expensive MRI. The patient’s insurance covers the MRI, making the costs a non-issue for that patient. There is no incentive to try ice, physical therapy, and rest before agreeing to the MRI. If the actual price of the MRI were clear, patients would know what they are “buying.” Patients could shop for MRI scanners just as they would for any other service, giving them control over how they spend their health care dollars.

This informed decision-making is particularly important for terminally ill patients. During the last six months of our lives, we spend up to 50% of our own total lifetime health care dollars; a quarter of all spending on Medicare, or more than $125 billion, goes toward services for the 5% of beneficiaries in their last year of life. Our practice in America, when patients are extremely sick and brought to the hospital, is to use everything in our medical repertoire to keep them alive. Costs can run at up to $10,000 per day of intensive care, not including other aggressive measures. Patients may not know these costs, or their options for palliative or hospice care—which is both cheaper and sometimes preferable. With patient-funded health savings accounts, patients would have more of a role in their own care, and could decide, based on a doctor’s recommendation, the best course of action, considering the prognosis, benefits, risks, and costs. Of course, every human being is unique in his or her health needs, and must make decisions in consultation with families. But some patients are now expressing a preference to avoid spending their last months hooked up to breathing tubes, postponing the inevitable. Doctors themselves, according to a recent article on the Health Care Blog, often make the decision to eschew aggressive medical treatments in their own last days. All in all, health savings accounts—as well as frank discussions between patents and their doctors—could facilitate better decisions about end-of-life costs.

Lastly, prevent chronic illnesses that end up costing Americans dearly as they age.

We are very good at treating complex medical problems in patients who are very sick, but not so good at reducing medical costs through preventative medicine. We are good at bringing a new blood-thinner drug to the market, but bad at preventing the conditions that require that drug in the first place.

Studies often point out that Americans spend a huge amount on health care, and yet are ranked lower than many other countries on health care outcomes. Here’s why: We spend a lot to prolong the lives of patients who are very sick—patients with multiple chronic medical conditions such as obesity, diabetes, kidney and heart disease—but we do little to prevent them from getting sick. In fact, 50% of our health care dollars ($623 billion) are spent on the sickest 5% of patients (30 million) in America. Within this group, the top 1% of health care “spenders” accounted for 20% of the total health care expenditures in America.

Recently, CNN’s Sanjay Gupta offered a practical solution to this problem. Obamacare will not in itself make people healthier, he wrote. Instead, he advised people to take ownership of their own health, and to hold themselves accountable. Eating better, exercising more, and reducing stress can go a long way to everyday health. It also helps avert those expensive chronic medical conditions.

Doctors experience first-hand all of the above issues on a daily basis and we have plenty to share with lawmakers, who are unfamiliar with the inner workings of doctor’s offices or hospitals. I believe that by empowering patients through health savings accounts, reforming our tort laws, making costs more transparent, being more realistic about end-of-life issues, and living healthier, we can make a real difference. I just hope that we can work with lawmakers to create a system that benefits everyone.