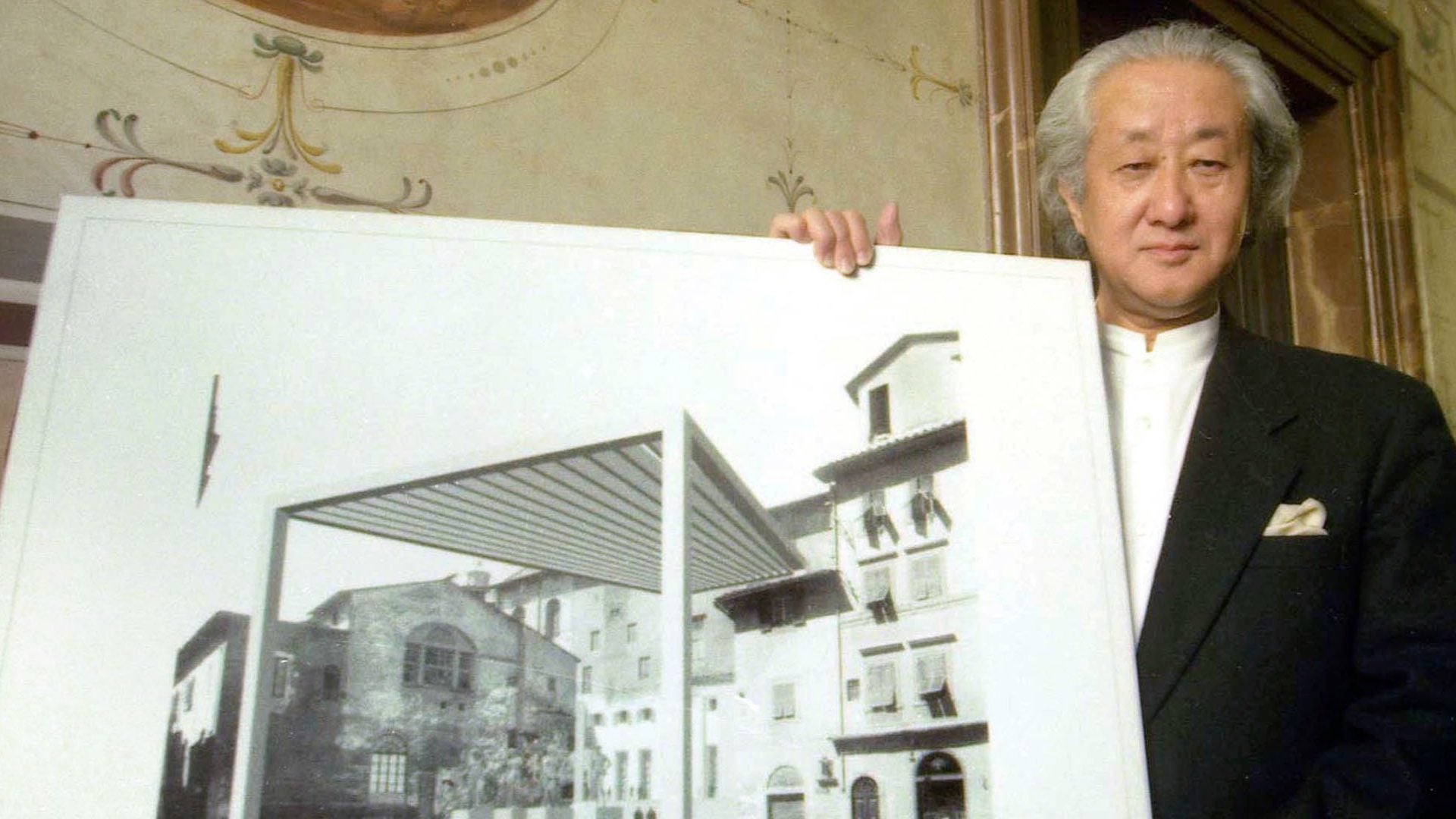

Arata Isozaki is the eighth Japanese architect to win the Pritzker Prize

The Pritzker jury has spoken. Architecture’s most coveted career honor goes to Arata Isozaki, the celebrated architect and theorist who began his career when Japan was rebuilding itself after the ruins of World War II.

The Pritzker jury has spoken. Architecture’s most coveted career honor goes to Arata Isozaki, the celebrated architect and theorist who began his career when Japan was rebuilding itself after the ruins of World War II.

In an interview at his home in Okinawa, the 87-year old architect tells the New York Times that he is “overjoyed” with the news. “It’s like a crown on the tombstone,” joked Isozaki. To his fans, the prize was overdue—some call him “the emperor of Japanese architecture” by his fans. The accolade comes with a $100,000 cash prize and a bronze medal that Isozaki will receive in France in May.

Isozaki was a teenager when Allied forces bombed his hometown of Ōita and nearby Hiroshima in 1945. “My first encounter in architecture was ground zero, no architecture, no city,” he says in a video produced by the Pritzker committee. ”I became interested in how architecture and a city can rise up from ground zero.”

Isozaki seized upon this blankness with daring and optimism. He designed avant-garde civic buildings in his town such as the brutalist gems Ōita Medical Hall and the Ōita Prefectural Library (aka Oita Art Plaza).”When it comes to peacetime, you cannot be adventurous, but quite mild and tame. However there is a time when anything is alright as long as it is interesting.”

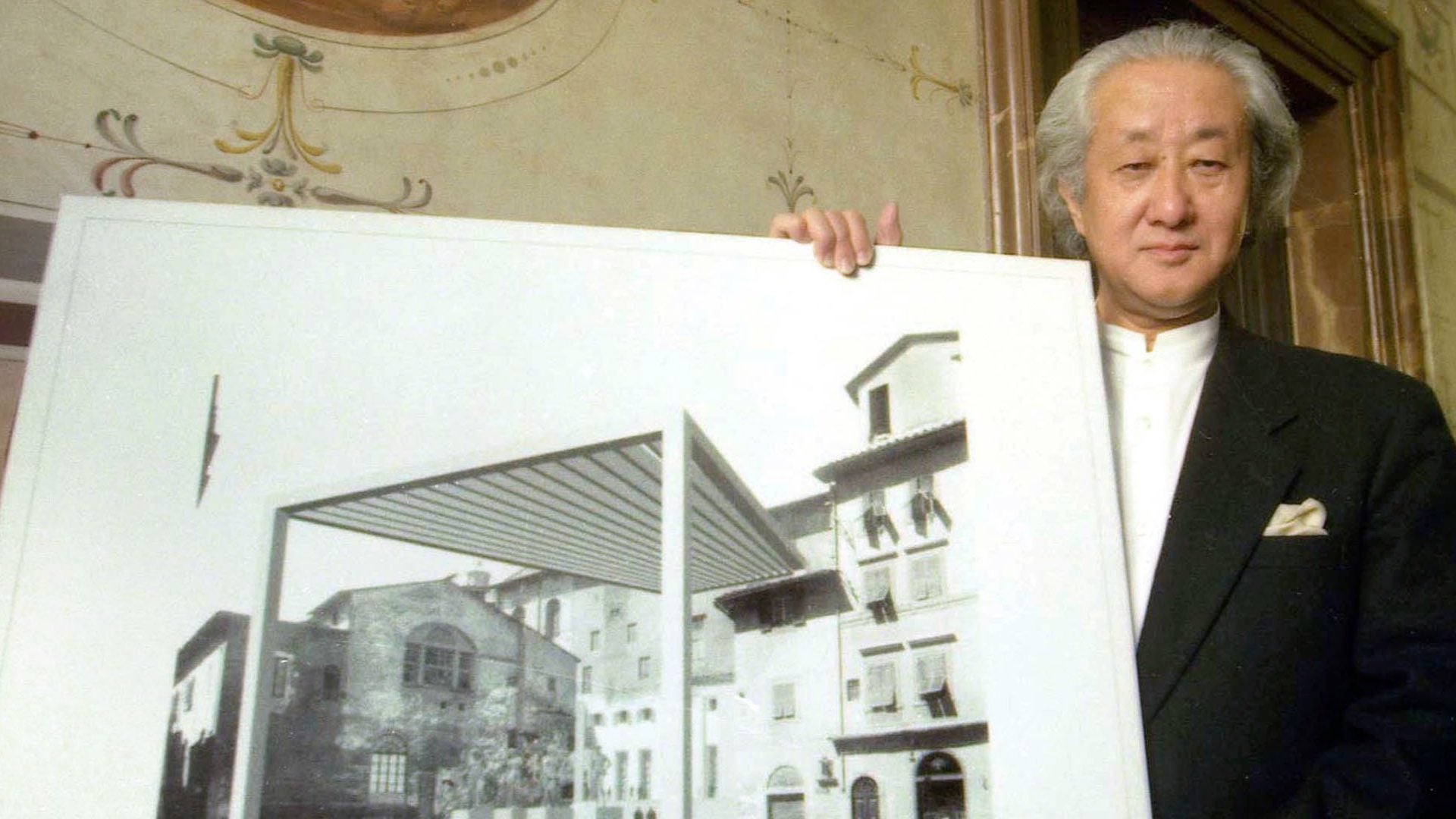

Abroad, Isozaki dazzled with avant-garde structures starting with Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, the red-brick postmodern gem paved the way to many international commissions. Among them is the Palau Sant Jordi in Barcelona, the Shenzhen Cultural Center, Qatar National Convention Center, the Shanghai Symphony Hall, and his favorite, the Museo Domus in northwest, Spain. Isozaki doesn’t subscribe to one architecture style, but his most famous buildings are categorized as Brutalist and Post Modernist.

Well into his 80s, Isozaki is working to create structures that inspire awe. Now, he’s focused on realizing aspects of his bold proposal called “City in the Air.” Originally conceived for Tokyo’s Shinjuku ward in 1962, Isozaki is winning over Chinese and Middle Eastern developers to his vision of “elevated layers of buildings, residences and transportation suspended above the aging city.”

Japan’s winning streak

Over the last four decades, a committee of architecture experts (chaired by a US Supreme Court judge this year), selects a living architect (or architects) whose work has made a “significant contributions to humanity.”

Pritzker Prize juries have been particularly attentive to Japanese architects. Isozaki’s mentor Kenzō Tange won the Pritzker in 1987, the first of eight Japanese-born architects to garner the prestigious international prize, considered by many as the industry’s Nobel Prize. The US also has eight laureates, counting Frank Gehry who holds dual citizenship in Canada and the US.

Winning the Pritzker isn’t only a great honor for individual architects, but it tends to draw an international spotlight to the architecture of their counties. The selection of Balkrishna Doshi as last year’s Pritzker laureate, for instance, was considered an overdue acknowledgement of the genius of South Asian architecture and urban design.