Nearly $1 trillion was smuggled out of developing countries in 2011

It’s hard to build your country when the money keeps slipping away.

It’s hard to build your country when the money keeps slipping away.

Foreign capital flight has been a problem for developing countries this year, but a bigger problem might be the funds smuggled out by tax evaders, corrupt officials and criminals—$946.7 billion in 2011, according to the latest estimates released today by a team of economists at the non-profit Global Financial Integrity, an increase of more than 10% over the previous year. For comparison, total foreign aid to developing nations in 2011 was just $141 billion.

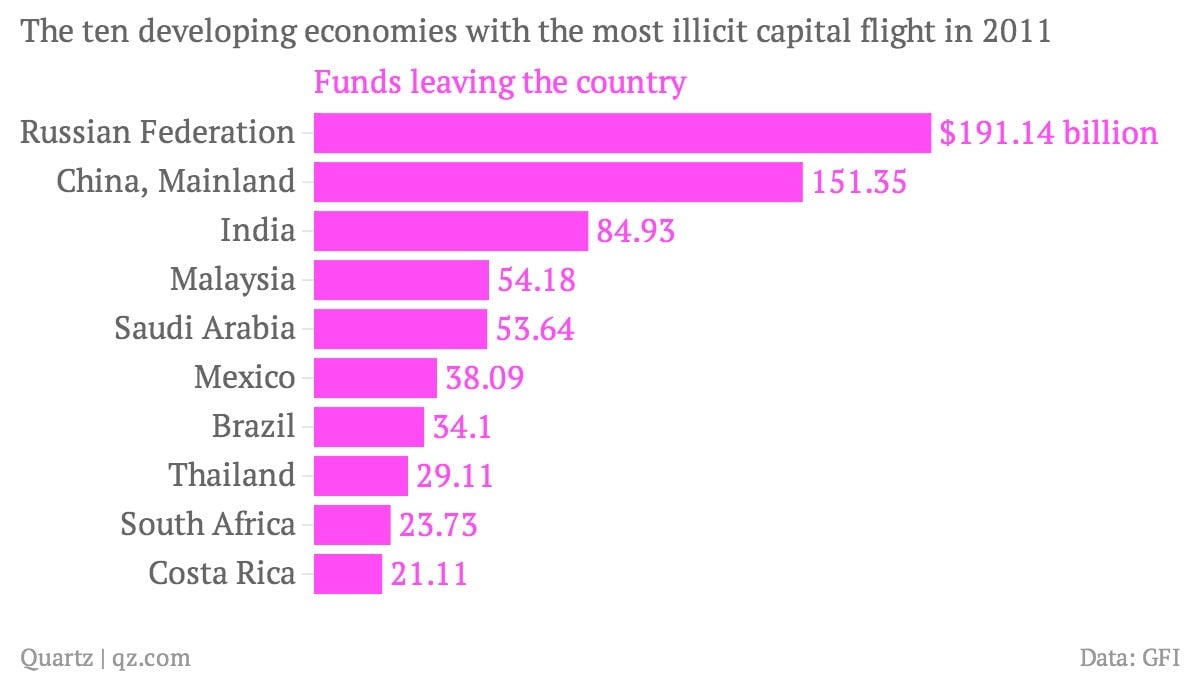

Russia topped the list, with $191.14 billion slipping out of its borders in 2011, followed by China with $151.35 and India with $84.93 billion. Economists at GFI identified the money by sorting through aggregate balance-of-payments data and finding mismatches that show where traders used creative invoicing to slip money out of the country—the bulk of illicit flows—or, about 20% of the time, through shell companies and tax havens. The global recession didn’t slow illicit financial flows, which have grown faster than global GDP each year between 2002 and 2011.

The specific reasons to get money out of a country vary by context, but include secreting away the proceeds of corruption; tax evasion, corporate and individual; fear of political reprisal, and drug and human trafficking.

The nations most hamstrung by illicit flows are in Africa, where illicit flows are the equivalent of 5.7% of GDP; the average developing country lost 3.7% of GDP in 2011. That’s a huge amount of money to lose that could otherwise be invested in private or public enterprise that might improve the lives of people living there. Instead, it winds up in tax havens—including the United States and the United Kingdom. “This isn’t really just a developing world problem it’s facilitated by developed country banks and tax havens,” Brian Leblanc, one of the economists behind the study, told Quartz.

Indeed, with six times more money leaving developing countries illicitly than entering them as aid, advocates for these nations might do well to back policies to block these flows. Promoting tax-haven crackdowns and convincing powerful multinationals to submit their transactions to more scrutiny is hard to do, but it could pay dividends for development down the line.