How you could have turned $1,000 into billions of dollars by perfectly trading the S&P 500 this year

What if you knew which stocks to invest in every day? What if every bet in the markets was a sure thing? What if you could put all of your eggs in one basket and never lose? How much could you have made in 2013 if you started with $1,000 to invest?

What if you knew which stocks to invest in every day? What if every bet in the markets was a sure thing? What if you could put all of your eggs in one basket and never lose? How much could you have made in 2013 if you started with $1,000 to invest?

Billions.

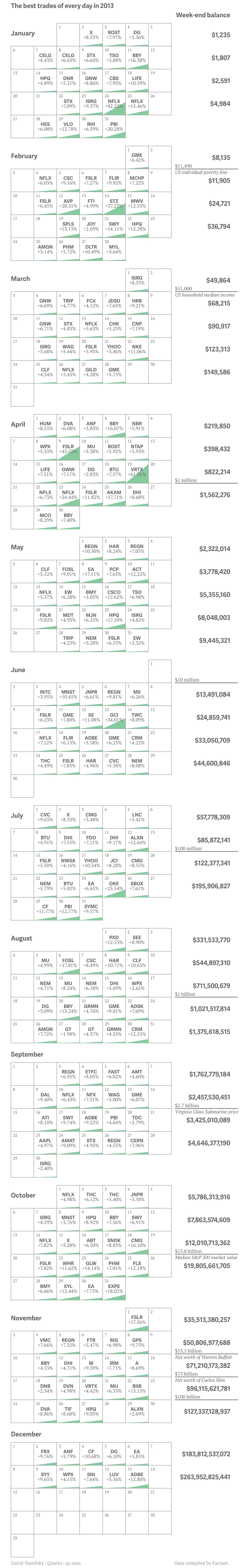

A trader who began the year with $1,000 in her brokerage account and put all of her money in each day’s best-performing equity in the S&P 500—day after day—for the 241 trading days so far this year would have $264 billion in her account today.

By March 4, her gains would have reached $53,200, exceeding the US household’s median annual income. She would have made a million dollars by April 23 while invested in Netflix, and a week later she would have doubled when her stake in Regeneron Pharmaceuticals grew 10.3% on May 1.

Her first billion would have come when AutoDesk saw 7.69% growth on August 23. By October 17, she would have had $10 billion. Less than a week later it would have been over $100 billion. In November, she would have become the richest person in the world.

Over the course of the year, she would have never taken a loss on any day. Here’s a day-by-day calendar of the S&P stock she would have had to invest 100% of her portfolio in to pull off the perfect trading year. (You can enter ticker symbols you don’t know here to see the full company names.)

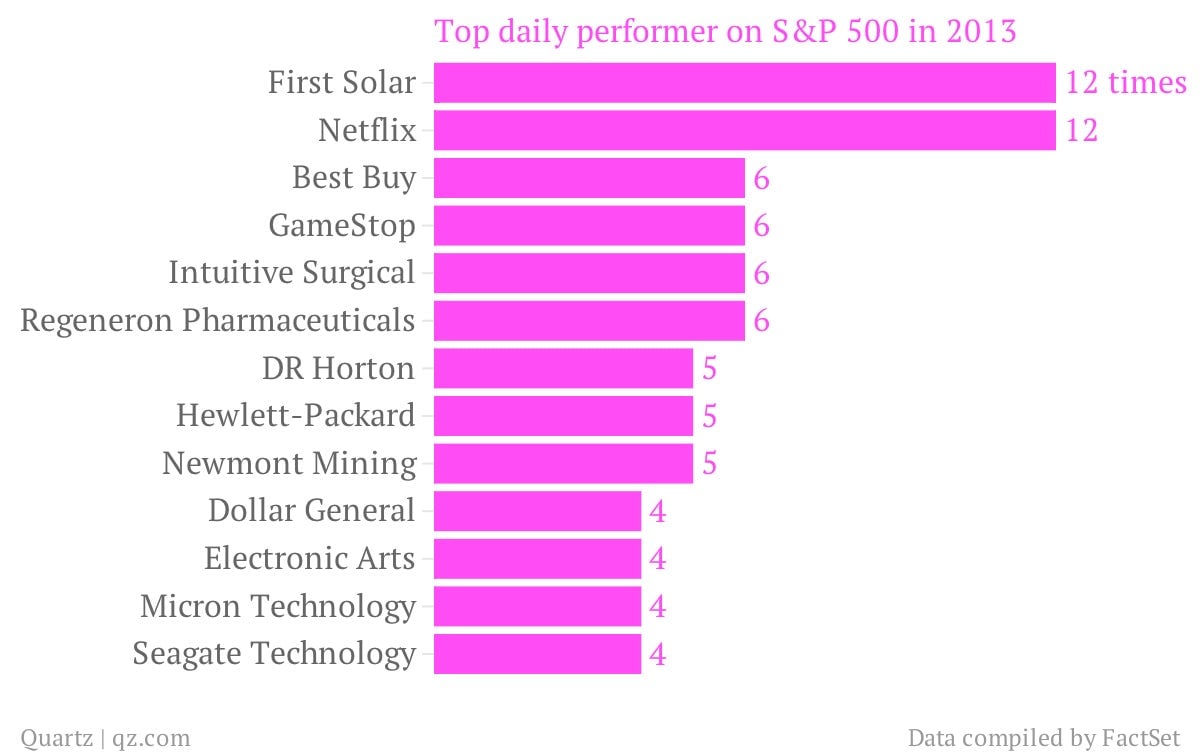

Although the S&P 500 has—as its name implies—500 members, only 129 companies were top performers on any of the 240 trading days this year. Here are some of the best:

Of course, once your investment had grown past a certain point, it would be impossible to put into any stock without drastically affecting the stock’s price. In many cases, investing this volume of cash would be impossible—in some cases there wouldn’t have been enough shares to buy. For our analysis we also did not take into account trading fees nor changes in the composition of the S&P index. We also assumed that all companies allowed for investment in fractional shares.

Moreover, even if one made the impossibly optimistic assumption that picking the best stock of the day is a 50-50 guess, there would be only a one-in-3.53 trevigintillion (3.53 x 1072) chance of matching these results.