Bill Gates calls Silicon Valley’s pursuit of immortality “egocentric.” Maybe he’s right

Life is short, the saying goes—and that was certainly true for the bulk of human history, during which global life expectancy hovered around 29 years. But over the past few centuries, the human lifespan has expanded by leaps and bounds. The life expectancy for a baby born in 2016 is 72 years, according to the World Health Organization.

Life is short, the saying goes—and that was certainly true for the bulk of human history, during which global life expectancy hovered around 29 years. But over the past few centuries, the human lifespan has expanded by leaps and bounds. The life expectancy for a baby born in 2016 is 72 years, according to the World Health Organization.

For the Silicon Valley elite relentlessly seeking ways to combat death and aging, that’s nowhere near long enough. But even as the new immortalists set ambitious goals of extending the human lifespan to anywhere from 200 years to over 1,000, it’s worth considering that less than 60 years of life—much of which is spent in poor health—is still the norm in dozens of African countries. As the life-extension industry begins to boom in Western nations, we should be asking ourselves the question: Who gets to live long and well, much less forever?

By the numbers

- Global life expectancy in 2016: 72 years

- Life expectancy in European countries in 2016: 78 years

- Life expectancy in African countries in 2016: 61 years

The historical eras in which life expectancy increased are called health transitions. These were first marked by reduced infant mortality in the 18th century, thanks in large part to a new understanding of germs and the implementation of basic sanitation protocols. Understanding the link between hygiene and health also helped to reduce maternal mortality rates in the 19th century.

By the 1870s, the flutterings of a health transition began in Oceania, Europe, and the Americas, which marked the first global increases in human life expectancy to a modest 34 years. African nations, by contrast, didn’t begin to see increases until around 1920.

The 20th century saw advancements in medicine that created further gains in life expectancy—for instance, the development of vaccines for communicable diseases like polio and the advent of antibiotics like penicillin. This was followed by the development of drugs that allowed us to control the spread of infectious diseases like HIV/AIDs and malaria.

However, increases in healthy life expectancy have not been as dramatic. That means that while people are living longer, they’re also living more years with illness, disease, and disability, particularly in the poorest parts of the world.

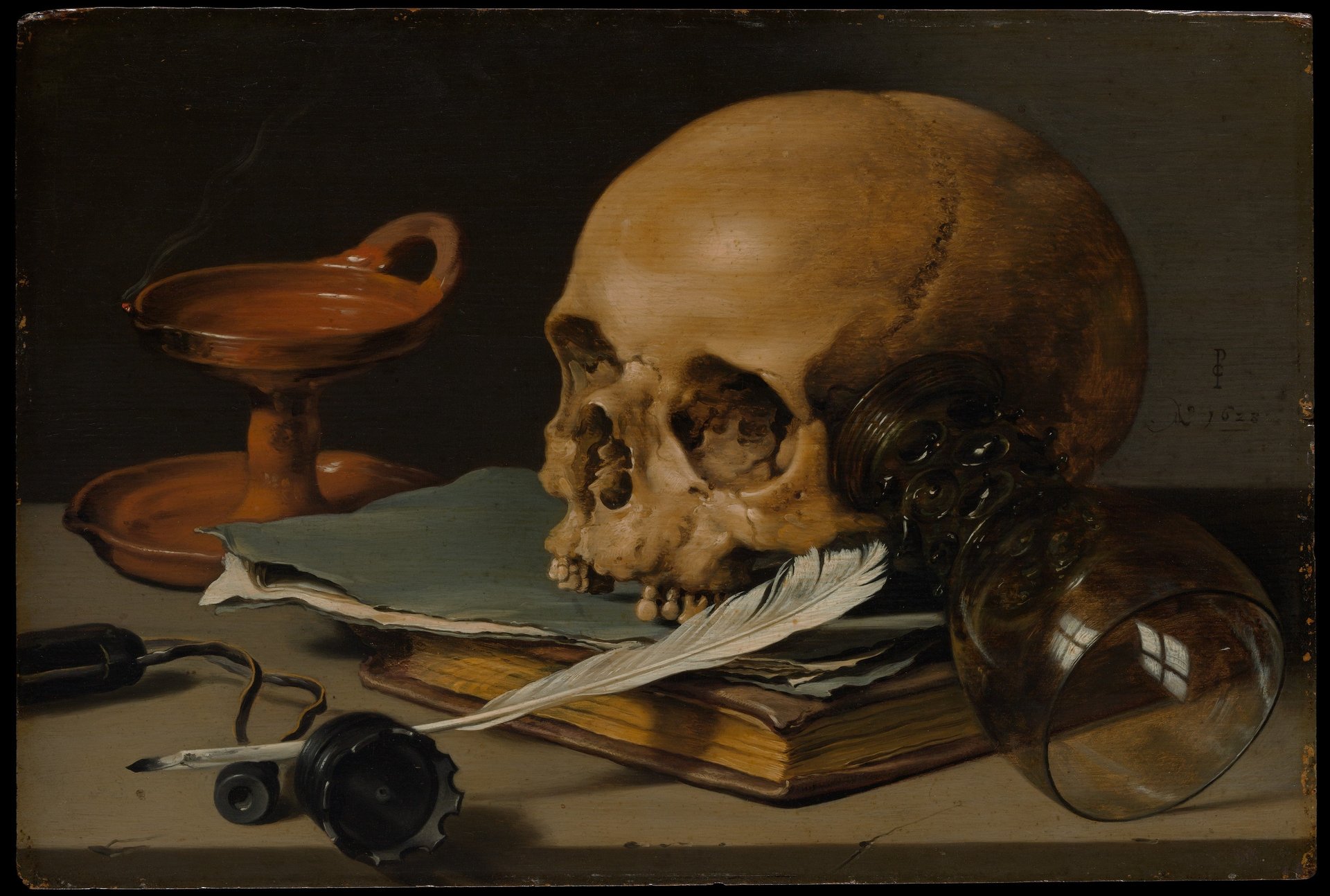

Aging, death, and disease

Since 1990—as health transitions began to spread on a global scale—people have started to live longer, meaning that older people are now dying at much higher rates than children.

By the numbers

- 1990 – 25% of global deaths were children under five

- 1990 – 33% of global deaths were elderly over 70

- 2016 – 10% of globals deaths were children under five

- 2016 – 48% of global deaths were elderly over 70

As a result, the top five global causes of death, according to data compiled by Our World in Data, are also the things that are killing the 70-years-and-older bracket. These are of great interest to the aging research community, and they’re what modern life-extension strategies are seeking to eradicate.

Top five global annual number of deaths by cause (2016)

For instance, as global life expectancy ticks up, rates of dementia have spiked rapidly in both high- and low-income regions in the past ten years, and they are expected to increase dramatically in the next several decades as aging populations increase.

It’s worth noting that causes of death differ substantially by age group and region. In Japan, for example, 83% of those who die are 70 years old or older, and less than 0.25% are under 15 years of age. In South Sudan, by contrast, 44% of deaths occur in children under five, and in South Africa—where HIV/AIDs is still the leading cause of death—the most fatalities occur in citizens between the ages of 15 and 49.

While the World Health Organization reports that most countries in its African region are making good progress on preventable childhood illness (such as polio and measles), HIV/AIDS and malaria continue to devastate it. A lack of basic sanitation, access to clean water, and a fragile healthcare system mean that many of the primary causes of death are less tied to age-related issues:

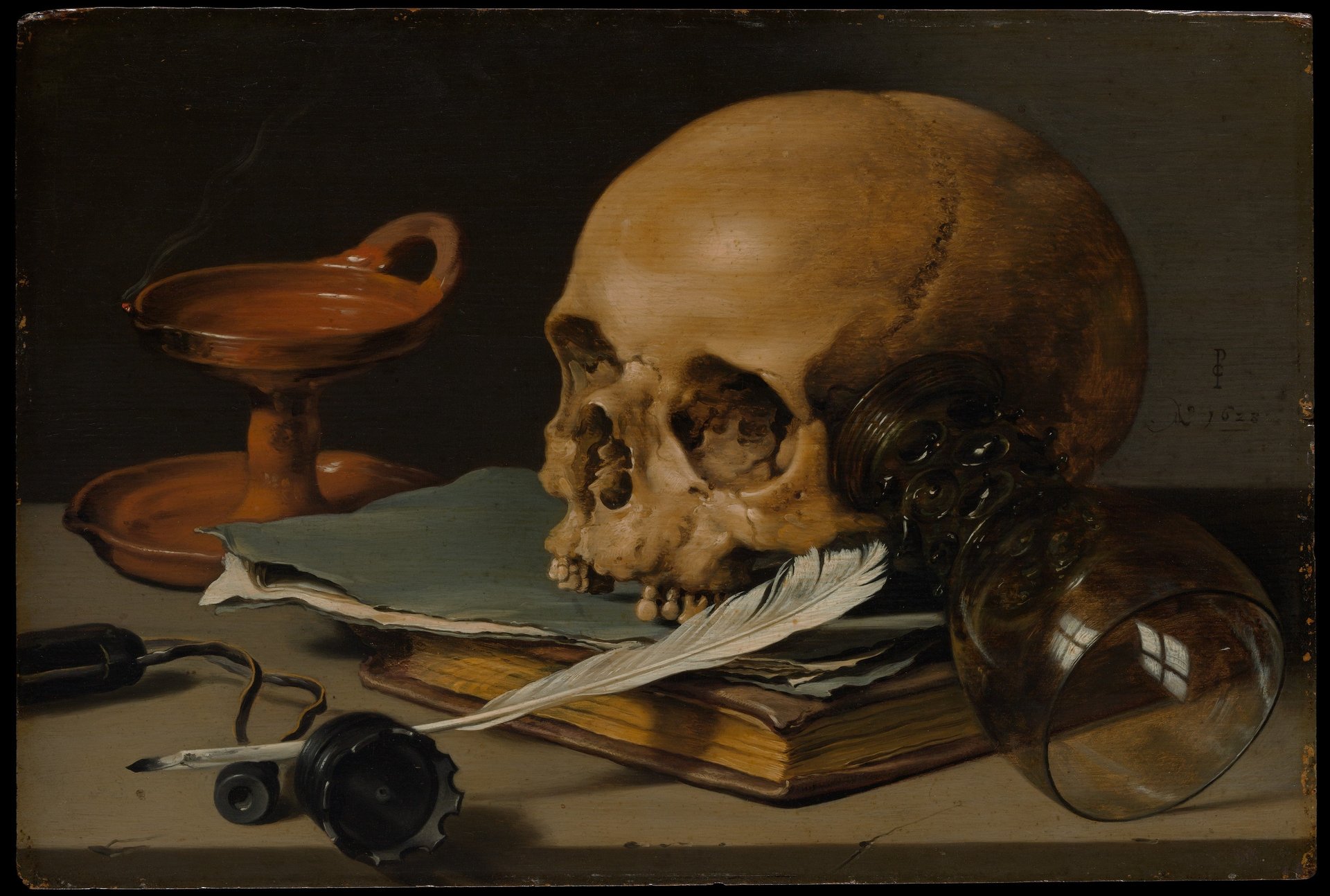

Who gets to live forever?

Historically, low-income nations have lagged far behind in life expectancy gains. For example, in the US, where the majority of life-extension technology is being developed, a person born in 1950 could expect to live anywhere between 20 to 25 years longer than one born in 1900. Every five-year interval since then has granted another one to two years of life to US citizens:

Compare that to Nigeria, the African continent’s most populous country. In 2010, the average life expectancy for anyone born in Nigeria was just over 50, a landmark the US had passed 100 years earlier.

Within this context, it’s perhaps unsurprising that Silicon Valley’s immoralists have such lofty goals about their own life expectancies. But others say that our priorities should be elsewhere: a longtime advocate for global health, Bill Gates has called his compatriots’ mission “egocentric” and continues to address inequities in health by addressing infectious disease and child mortality in developing countries via the Gates Foundation. It’s a cause championed by the likes of billionaire Warren Buffett, who pledged $30 billion to the organization in 2006.

For the most part, the “longevity entrepreneurs,” investors, and lifestyle gurus investing in radical life extension seem to swat the criticism that longevity is vanity mission away. Several that Quartz spoke to pointed out that sanitation, starvation, clean water, and disease eradication “are still going to be problems we have to fix,” whether we live another 100 years or not.

That might be true, and most scientists would agree that increasing investments in longevity research are not necessarily a detriment to global health. However, there is a risk that more resources will be dedicated to the diseases that affect people after what are relatively long and pampered lives, rather than the infectious diseases and nutrition-related illnesses killing people in low-income nations. In that context, Gates’ egocentric accusation doesn’t seem so far off the mark.