Prosecutions for death threats against US politicians spiked last year

Arrests for violent threats against high-profile US politicians spiked in 2018.

Arrests for violent threats against high-profile US politicians spiked in 2018.

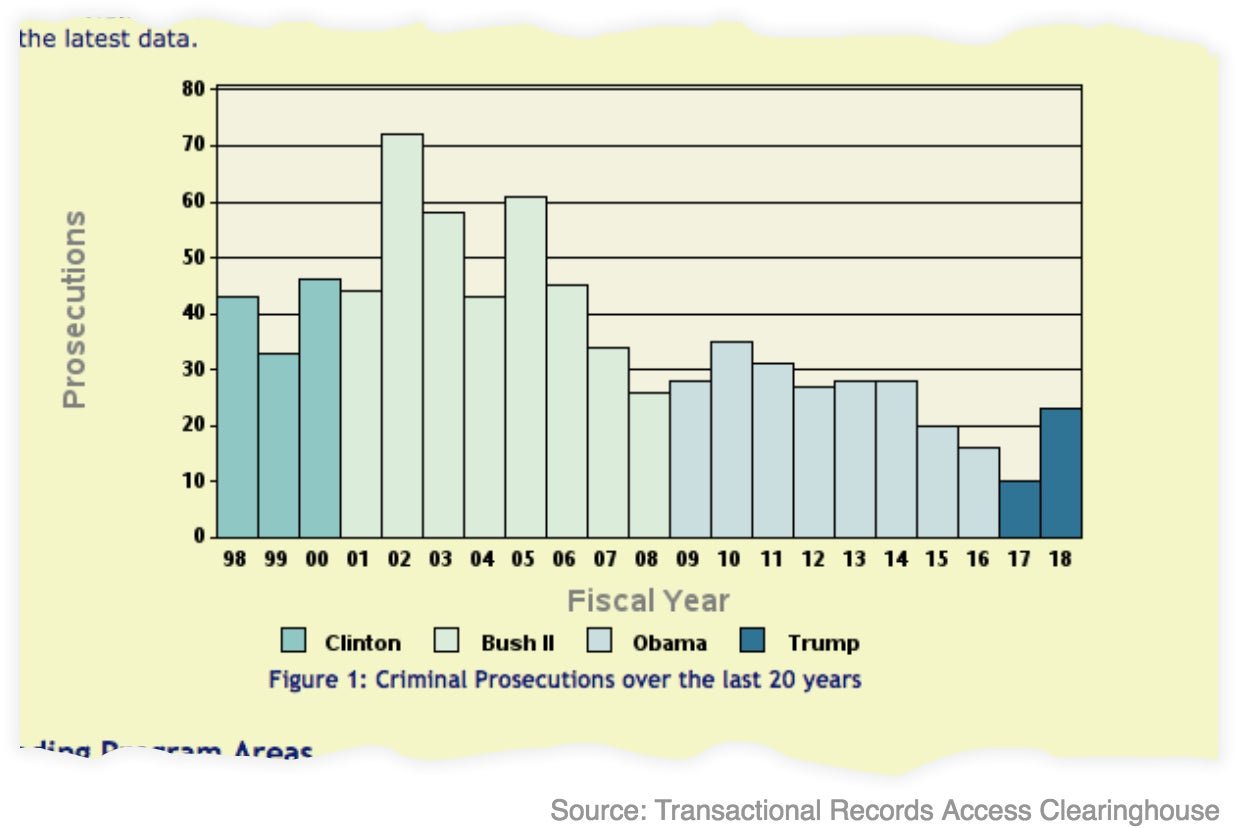

There were 23 prosecutions for threats against Donald Trump or those in the presidential line of succession last year, a 130% increase over 2017, when there were 10, according to Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC). The uptick came after five years of steady decline.

The number of prosecutions, which don’t necessarily correspond with actual threats, can represent the government’s willingness to press cases at any given time. Researchers say the vast majority of threats overall in the US tend to come from white men who support right-wing causes.

Three cases involving defendants who threatened the lives of political figures came to various stages of resolution in federal courtrooms last week.

In one, an upstate New York man was convicted of threatening to kill former president Barack Obama and congresswoman Maxine Waters, the California Democrat. In another, a California man was sentenced for threatening the lives of Obama, former presidents George H.W. Bush and George W. Bush, and Trump. In the third, Cesar Sayoc, the Florida man charged with mailing 16 package bombs to more than a dozen political figures and media outlets seen as critical of Trump—including Obama, Waters, Hillary Clinton, and CNN—pleaded guilty to 65 counts. (On March 22, Waters issued a statement noting that four men have been convicted of threatening to kill her since Trump took office in 2017.)

Anyone who “knowingly and willfully threatens to kill, kidnap, or inflict bodily harm” upon the president, vice president, ex-presidents and ex-vice presidents, members of their families, presidential and vice presidential candidates, or members of their families (within 120 days of the general election) faces up to five years in prison on each count and a $250,000 fine. Threatening to kill a member of Congress carries a sentence of up to 10 years; six for threatening an assault.

A Secret Service spokesman declined to say how many open threats they are investigating against the president and the other individuals the agency protects. Past estimates have varied from as few as six per day to as many as 30 during the Obama era.

Threats in recent decades

Here is a look at prosecutions for threats against sitting presidents, as gathered by the Syracuse team:

In 2010, Democratic lawmakers reported receiving at least 10 death threats over their support of the Affordable Care Act. Republican congressman Eric Cantor also got death threats at the time for his opposition to Obamacare and a window was shot out at his office in Richmond, Virginia.

Michael Loadenthal, director of the Prosecution Project (tPP), a statistical modeling lab at Miami University of Ohio, says federal decision-making dictates how prosecutorial focus and strategy fluctuate with administrations and the prevailing political climate. He noted that in the weeks, months and years following the 9/11 attacks of 2001, there was a surge in prosecutions of defendants with links to Muslim-majority countries.

“These arrests subsided in the Obama years as US strategy changed focus, and Obama shifted focus to extrajudicial assassinations overseas,” Loadenthal tells Quartz. “We can expect these patterns to wax and wane as administrations determine and refocus their attention, determining for themselves what constitutes a notable threat to the lives of elected officials.”

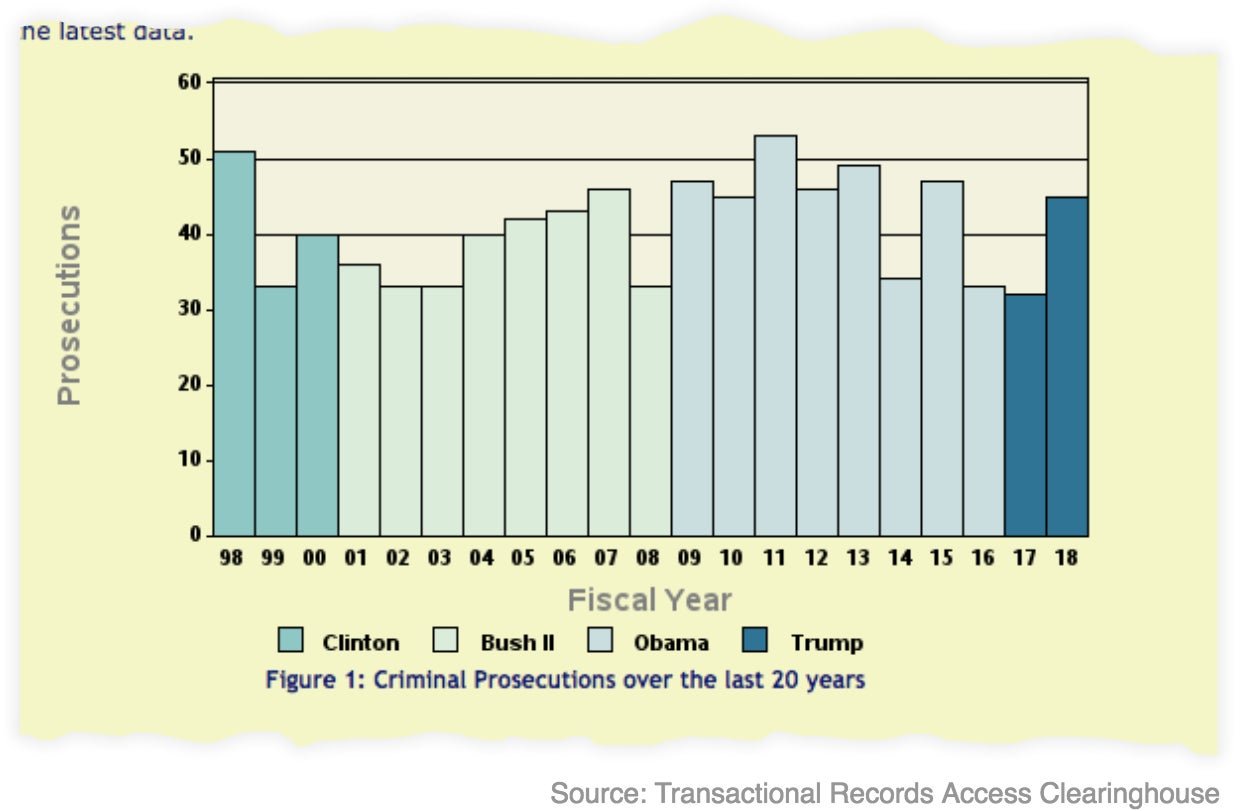

Prosecutions for threats against federal officials in general were up 41%, with 45 in 2018. It’s the highest rate in the past two years, but down 8% as compared to 2013. The level was highest in 2011, during Obama’s first term, with notable totals in his second term as well:

Where the threats come from

A data analysis performed for Quartz by Athena Chapekis and Lauren Donahoe of the Prosecution Project found that about 75% of those charged for making threats against US politicians come from the ideological right, based on cases going back to 1990. They are almost entirely US citizens, male, and roughly 85% white. About half of the defendants were under 30. The intended targets were primarily Democrats.

Trump has rejected the idea that his own rhetoric may be responsible for inciting any threats or attacks. After Trump seemed to imply at a campaign rally that Hillary Clinton should be shot, CNN reported that the Secret Service spoke to the then-candidate more than once about his comments. Trump denied such a conversation ever even took place.

“It seems entirely logical that people who feel change is possible through the ballot box don’t feel compelled to engage in extrajudicial violence,” says Loadenthal. “At the same time, there is a rise in right-wing violence, which is somewhat paradoxical.”

A 2011 study by Nathan Kalmoe, now an assistant professor of political communication at Louisiana State University, found that “even mild violent language increases support for political violence among citizens with aggressive predispositions, especially among young adults.”

Court filings by the defendant’s lawyer in the upstate New York case link his threats to Waters and a June 2018 tweet by Trump in which the president called her “an extraordinarily low IQ person.” Now awaiting sentencing, maintenance worker Stephen John Taubert, 61, was also agitated about the infamous 2017 photo in which comedian Kathy Griffin posed holding a bloodied Trump head as a stage prop, documents from the trial indicate.

How the Secret Service assesses threats

Jonathan Wackrow, a former Secret Service agent who was part of Obama’s protective team, says that “a slight variation in language” can mean the difference between agents showing up at your front door or not.

“There is an investigative process that takes a very deep dive into everything I can possibly know about this individual,” Wackrow tells Quartz. “You go backwards and look at past incidents—problems at work, behavioral problems, does this person have access to firearms?”

Agents then assign a risk rating to each person who make a threat that is discovered. The higher the rating, the more attention they can expect to get from agents. Check-ins can include a periodic email, a phone call, or an in-person interview. The ones who seem most prone to violence might find a Secret Service vehicle parked outside their home when the president is in their town.

“What we’re looking for are changes in behavioral patterns,” says Wackrow. “Everybody who makes a threat against the president doesn’t get arrested, but we keep track of them and many times that’s what keeps them from transcending into physical action.”

A link to mental illness

Roughly 75% of people who come to the attention of the Secret Service as potentially dangerous suffer from some sort of mental illness, according to the Justice Department.

“Putting them in jail is a last resort, it’s not like normal law enforcement,” says former Secret Service agent Angela Hrdlicka. “Oftentimes, they need mental-health treatment, and they’re not going to get any better in jail.”

Simply making a threat is often not a major risk factor, she tells Quartz, explaining that a person that is “highly motivated to do harm won’t typically verbalize it.”

“Everybody has stress,” Hrdlicka says. “We’re looking for people who are at their breaking point.”

US courts have tried to strike a balance between the government’s desire to protect the president and Americans’ free-speech rights. The difference between a threat and political speech hinges upon whether a “true” threat was made “knowingly and willfully,” per federal law.

The Secret Service’s “protective intelligence reports” reflect a suspect’s criminal history and “the opinion of the investigator, based on the facts—talking to that person’s roommate, spouse, whoever is in a position to know what his activities have been recently,” says Hrdlicka. Agents are looking for signs of the intent to do harm and the ability to execute on it.

When a joke is not a joke

Tech entrepreneur Matt Harrigan says he was just kidding around with his buddies (and a bit drunk) when he wrote a Facebook post a few days after the 2016 election: “I’m going to kill the President Elect. Bring it secret service.”

Harrigan, now 44, tells Quartz it was a friend of a friend grabbed a screenshot, stripped the image of necessary context (he says his post was accompanied by a picture of Ron Burgundy, the Will Ferrell character from Anchorman, as part of a larger joke among his friends), and circulated it on alt-right message boards. That’s when Trump fans began appearing at Harrigan’s San Diego, California home, threatening to kill him and his family.

A few days later, the Secret Service showed up.

The agents questioned Harrigan, evaluated his psychological state, and searched his home. Harrigan, who described his message to the Washington Post as “a very bad joke in very poor taste,” says the agents seemed aware from the start that he was not a threat. But they were still required to go through the investigative process.

“The end result was that the Secret Service was required to interview me, which was very unfortunate, as I’m sure they have actual important work to do,” says Harrigan, who lost his job at the company he founded over the incident.

“They looked around the house, and that was it,” says Harrigan.

He says he hasn’t heard from the feds since.