Panera’s “gift economy” experiment failed and now the IRS is coming

For almost a decade, at five locations across the US, a hungry customer could get a Panera sandwich for free, no strings attached.

For almost a decade, at five locations across the US, a hungry customer could get a Panera sandwich for free, no strings attached.

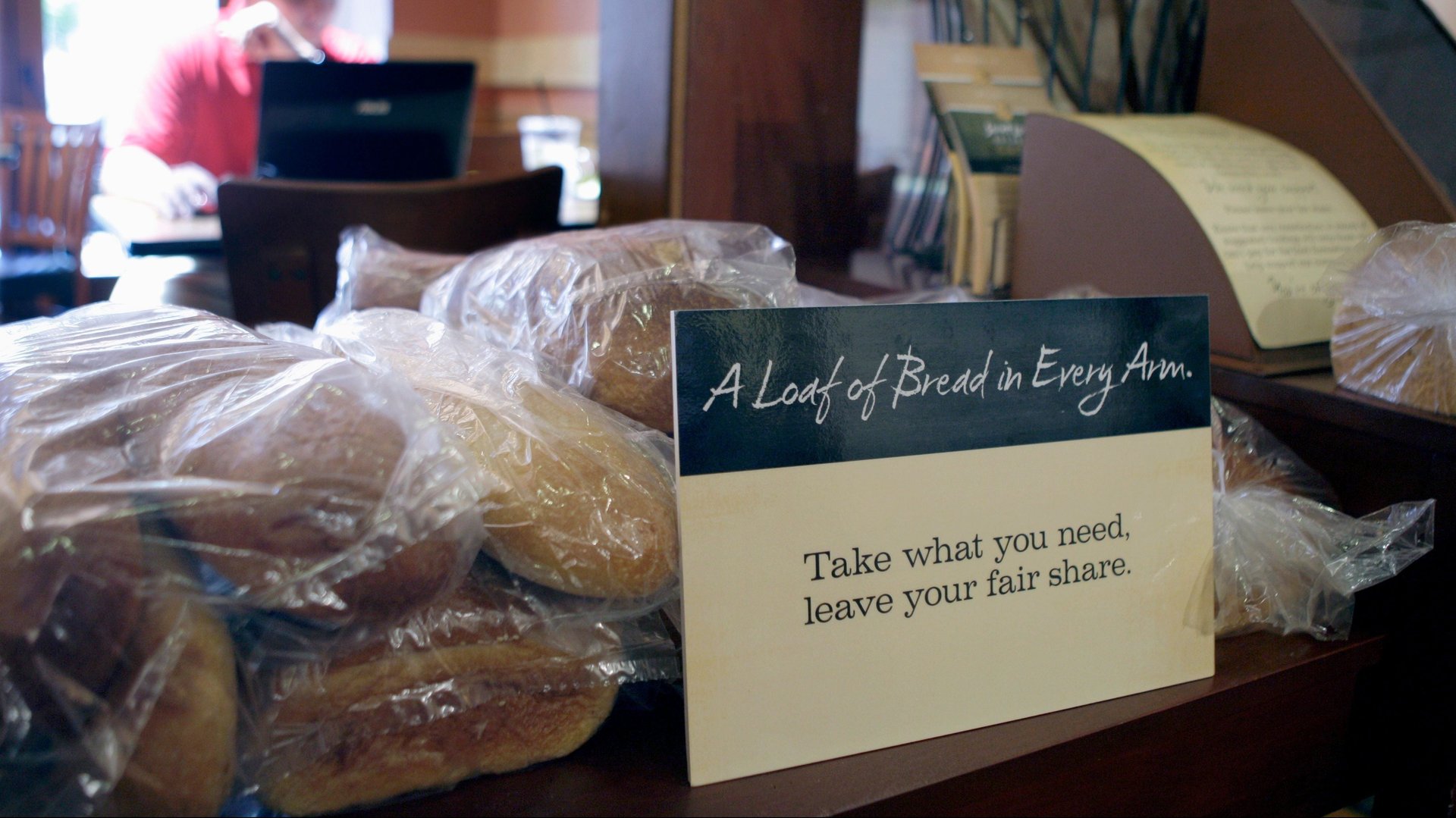

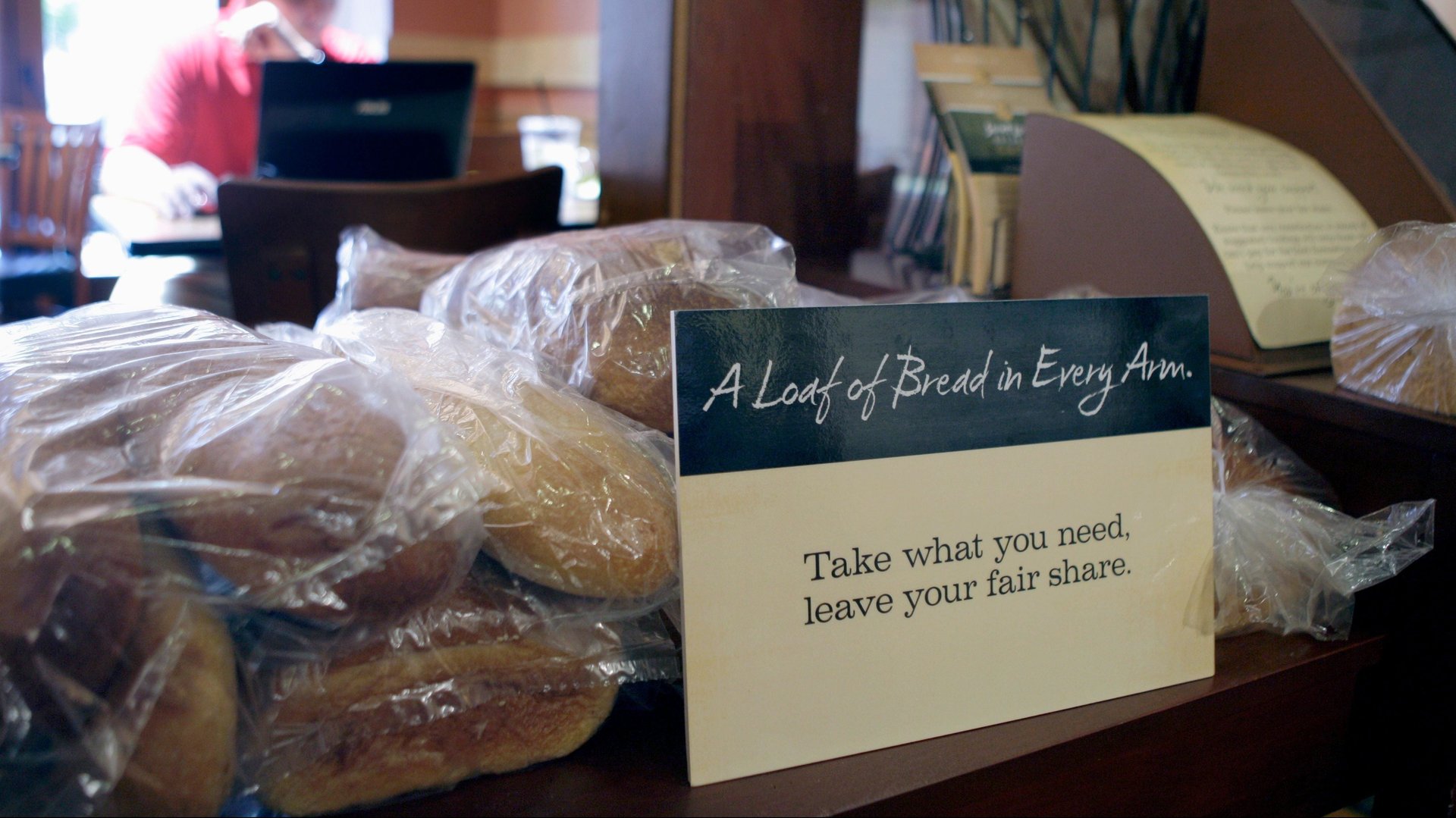

The US chain of casual restaurants was conducting an experiment where wealthier patrons could help feed the hungry by subsidizing their meals. At the five Panera Care Cafés in Chicago, Boston, Portland and suburban Detroit and St. Louis, from 2010 until last month, customers could pay whatever they wanted, from nothing to a lot, or somewhere in between. To further donate, those who could were encouraged to volunteer their time and energy at the cafés as free labor. (Panera says it had more offers of labor than it could possibly use.)

This kind of “gift economy” has echoes of those employed by Burning Man, the Buy Nothing Project, a number of Papua New Guinean indigenous tribes, and the dissemination of a widely pirated 2007 Radiohead album. In a gift economy, it’s not so much that everything is free, but rather nothing has a fixed cost. Things aren’t necessarily bought or sold, they’re simply given, with the assumption that people will take what they need and give what they can, even if there’s no explicit agreement for immediate or future rewards.

Profit doesn’t need to be a concern, because a combination of obligation and generosity on either side means it all balances out. Unlike a simple charity, where people give to a larger organization that then gives on their behalf, a gift economy works because everyone is giving, and receiving, labor, goods, and money all of the time.

“In many ways, this whole experiment is ultimately a test of humanity,” company founder and former CEO Ron Shaich said in a 2010 TEDx talk. “Would people pay for it? Would people come in and value it?”

“It” was the Panera Bread Foundation, an IRS-designated 501(c)(3) “private charity” launched earlier that year with the goal of helping the poor, providing education to at-risk youth, and promoting health and welfare.

People did give—but they seem to have been much more interested in taking. The five cafés saw themselves beset with starveling students and whole shelters full of homeless people, who complained that the restaurant had become unwelcoming to those who took its “pay-what-you-can” edict at face value, where the poor were accused of “abusing the system” or publicly shamed at the check-out.

A year after opening, at the Portland location, the outlet was making about 70% of its operating costs, even after banning students from visiting during school hours. Eventually it employed a “community outreach manager,” to gently usher out unwelcome diners and teach them that “this is a cafe of shared responsibility and not a handout,” Shaich told the Portland Tribune. “It can’t serve as a shelter and we can’t have community organizations sending everybody down.”

One by one, the cafés shuttered, citing a lack of financial viability. In February, the very last example, in Boston, closed its doors. Now, according to last week’s report from Law360, the IRS has taken a closer look at this so-called “non-profit,” and says it owes a hefty tax bill going back to 2012 on annual revenues exceeding $7.5 million.

So far as the IRS are concerned, the cafés were primarily profit-making enterprises, rather than anything “inherently charitable.” (The fact that they closed because they weren’t making any money supports such a claim.)

Panera, in its defense, say it operated the cafés to literally feed the poor—what could be more charitable than that? In a slightly weaker line of argument, the company argues that it was providing “a valuable educational experience” by giving people of means the opportunity to “stand in line” with “individuals lacking means to purchase food.” These wealthier folk would “otherwise … rarely interact with someone who was hungry.”

To be deemed “publicly supported” by the IRS, organizations must take at least a third of their financial support from donations: Panera Cares Cafés’ public support made up close to 58%, the company said. It is not clear whether these were actually donations, in-kind donations of labor, or people simply paying above the sticker price on their lunch.

A 2018 article published in the Journal of Business Ethics seems to come down quite firmly on the side of the IRS. Academics Giana M. Eckhardt and Susan Dobscha argue that Shaich was attempting to monetize people’s desire to “demonstrate their ‘goodness’ at the cash register,” by “paying more than the displayed price for their meal” and thus generate profit for the business. Though some people may indeed have wanted to signal their virtue, others were uncomfortable with a pricing system that put the onus on them —a rude awakening to a gift economy system that does expect people to behave selflessly.

In a further blow to Panera’s charitable aspirations, the experience of dining alongside the “food insecure” did not, as Panera’s filings suggested, facilitate interclass communication and mingling. Instead, Eckhardt and Dobscha found, wealthy people felt disdainful of their fellow diners; the homeless or poor, “rather than being empowered via a dignified dining experience,” felt ashamed or uncomfortable. All that, and hungry to boot.