Jakarta’s crackdown on freelance traffic cops won’t solve its apocalyptic gridlock

Jakarta’s traffic is simply brutal: Commuters spend hours every day stranded in cars and crammed into battered busses in the congested Indonesian capital, which has about 28 million residents but no rapid-transit system.

Jakarta’s traffic is simply brutal: Commuters spend hours every day stranded in cars and crammed into battered busses in the congested Indonesian capital, which has about 28 million residents but no rapid-transit system.

Opportunistic vendors often weave between the stopped vehicles, selling snacks like fruit and nuts, and motorcycle taxis offer rides between lanes. But now the city is cracking down on one particular sort of gridlock-inspired entrepreneur: the pak ogah, or independent traffic guide. For a small fee, the whistle-bearing boys or men will help drivers merge into crowded lanes or make U-turns. They also often take charge of busy intersections and railroad crossings. A recent local news report, for example, showed an especially enthusiastic traffic guide.

The guides have faced scrutiny, however, following a deadly collision last week between a train and a fuel truck. Some bystanders said the local guides failed to prevent the truck from driving across the tracks. Jakarta’s governor, Joko Widodo, now wants to fine guides at railroad crossings 500,000 rupiah (about $41), and his deputy wants them banished city-wide. “We have to catch them all, and clean this up,” said Vice-Governor Basuki “Ahok” Tjahaja Purnama, according to the Straits Times.

Comparative data about traffic congestion is scarce, but by any measure Jakarta has it rough. About 10 million vehicles hit the roads each workday, and commute times are further worsened by seasonal factors like monsoon rain and workers leaving their offices at set times during the Muslim holy month of Ramadan. As in other Southeast Asian megacities like Bangkok and Manila, newly affluent middle-class car buyers are making matters progressively worse: In 2012, average car speeds in the city were just 16 kilometers per hour (about 10 miles per hour), compared to 20 kilometers per hour in 2008.

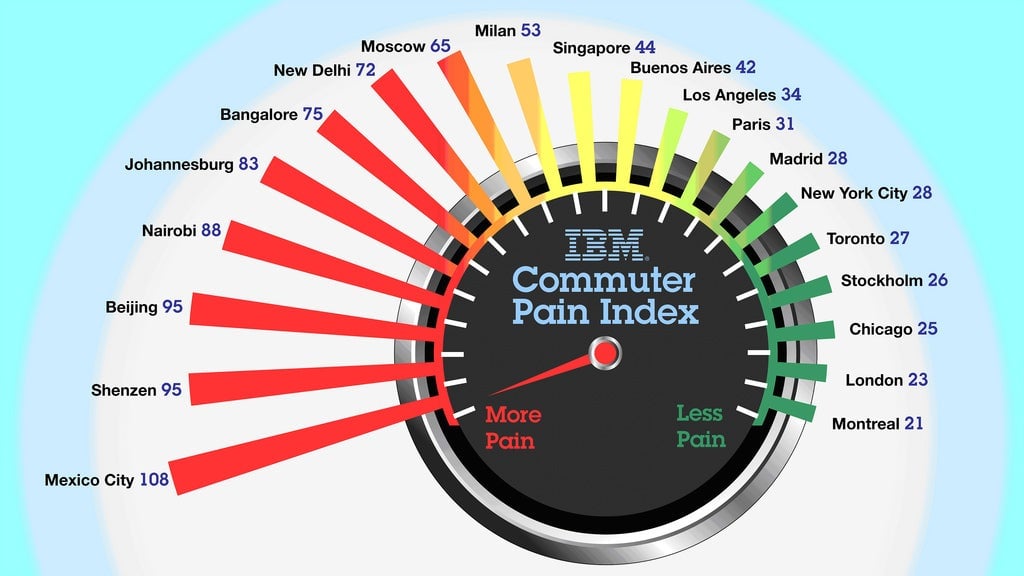

Jakarta wasn’t one of the cities surveyed for this 2011 IBM study of the world’s worst cities for road traffic, but based on the metrics that included commuting time, time stuck in traffic, worsening conditions and standstill conditions, it would probably rank near the top of the list.

It’s hard to see how blaming the pak ogah or cracking down on their attempts to impose a bit of order on the chaos will help ease the severity of Jakarta’s traffic.

“They have been here for the longest time and there is some sort of informal understanding that they are allowed to operate,” one traffic guide told the Straits Times. “So as long as there is weak enforcement, they will be here.”

In the meantime, commuters can cast a longing eye toward the day in 2018 when Jakarta’s first mass transit system, the MRT, is scheduled to begin operations. Until then, construction associated with the underground and overhead railway is expected to cause—you guessed it—even more traffic jams.