The UK’s national minimum wage is 20 years old, and employment has never been higher

Twenty years ago today, the UK introduced a national minimum wage. From April 1, 1999, workers aged 22 and over would earn at least £3.60 ($4.71) per hour. It was estimated that the introduction of the rate would increase total UK labor costs by about £2.4 billion a year.

Twenty years ago today, the UK introduced a national minimum wage. From April 1, 1999, workers aged 22 and over would earn at least £3.60 ($4.71) per hour. It was estimated that the introduction of the rate would increase total UK labor costs by about £2.4 billion a year.

At the time, the new law was criticized—including by members of the Conservative party who are in government today and continue to expand the law—as a policy bad for small businesses that would squeeze people out of some low paid jobs, worsening unemployment. These ideas tended to follow basic economic rules around supply and demand, that suggested higher wages would reduce demand for workers. (There’s much more empirical evidence—pioneered by the late US economist Alan Krueger—now that shows it’s not so simple.)

After two decades, the UK’s Low Pay Commission concluded in a report published today that the national minimum wage has not had an adverse impact on the UK’s job market. “Rather than destroy jobs, as was originally predicted, we now have record employment rates,” Bryan Sanderson, the chair of the Low Pay Commission, wrote in the report. “The overwhelming weight of evidence tells us that the minimum wage has achieved its aims of raising pay for the lowest paid without harming their job prospects.” Rather than cutting jobs, businesses have adjusted by cutting profits and increasing prices. The UK’s employment rate is at a record high 76.1%, while the unemployment rate is at 3.9%, the lowest since 1974.

In 2018, the lowest-paid workers earned £2.70 per hour more, adjusted for inflation, than if there had been no minimum wage, amounting to about £5,000 a year for a full-time worker, according to the Commission. Over the years, seven million people, or 30% of the workforce benefited directly or indirectly from the law.

In 2016, the national living wage was introduced to replace the minimum wage for those over 25. It’s a higher rate than the minimum wage was and the governing Conservative party have said they intend for the national living wage to be 60% of the median income by 2020. Today, the national living wage increased to £8.21 per hour, directly increasing pay for two million workers. Workers under 25 are still paid a minimum wage that is adjusted by age.

Before the national minimum wage was introduced, earnings for the lowest-paid increased more slowly than average. That trend has now been reversed with hourly pay for the lowest paid rising faster than for all other workers. In the past two decades, the bottom fifth of workers have had real pay growth of 40%, twice as fast as the rest of the workforce, according to the Resolution Foundation, a think tank dedicated to studying UK living standards. The Low Pay Commission estimates that between 1999 and 2018, the total benefit to workers from minimum wage increases has been £60 billion.

By international standards, the UK’s increases to minimum wages are also impressive. Among OECD countries, the UK was in the middle of the pack but by 2020 only New Zealand and France are expected to have higher wage floors, an improvement the Resolution Foundation called “staggering.”

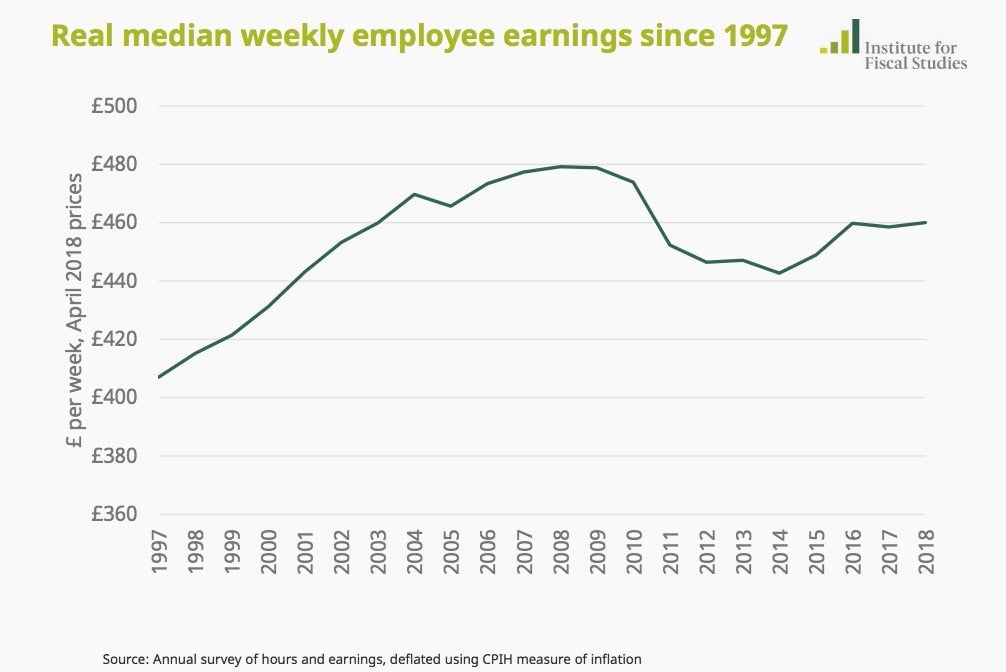

While the success of the national minimum wage is being celebrated, the UK is dealing with a broader pay crisis. Since the financial crisis, the average worker has suffered a “lost decade” of wage growth. In real terms, median wages are below where they were in 2008. There has been no period like this since the early 1800s.

Meanwhile, there are limits to how much an increase in the minimum wage can reduce inequality. Even as it substantially increased hourly pay, there is evidence of weekly pay inequality worsening because some groups are now working fewer hours. “Some people may have chosen to work fewer hours, but we also know lower earners often can’t get the hours they want with the security they need,” the Resolution Foundation said, noting that weekly pay for the bottom 30% had fallen.