The inside story of how CATL became the world’s largest electric-vehicle battery company

CATL doesn’t have a 100-year track record of reliability like Panasonic; it isn’t based in a rich, developed country like LG Chem; and it isn’t backed by Warren Buffett like BYD. Regardless, in less than 10 years, Contemporary Amperex Technology Ltd. has beaten its competitors to become the world’s largest maker of lithium-ion batteries.

CATL doesn’t have a 100-year track record of reliability like Panasonic; it isn’t based in a rich, developed country like LG Chem; and it isn’t backed by Warren Buffett like BYD. Regardless, in less than 10 years, Contemporary Amperex Technology Ltd. has beaten its competitors to become the world’s largest maker of lithium-ion batteries.

When CATL listed on the Shenzhen stock exchange in 2018, it minted four new billionaires. The company supplies more than 40% of all batteries that go in electric vehicles in China, where more EVs are sold than the rest of the world combined. CATL is currently filling orders not just from Chinese carmakers but also from global brands like Volkswagen, Daimler, BMW, and Honda.

Last month, CATL began construction on its fourth gigafactory, the company’s first outside of China. Located in Germany, the new plant will place CATL and Chinese technology right at the heart of German car manufacturing.

CATL is the epitome of what the Chinese government had in mind when, in 2009, it marked out electric cars and lithium-ion batteries as strategic industries and enacted policies to spur their growth. In the decade since, the government has spent more than $60 billion to create a domestic EV industry while simultaneously implementing regulations supporting the domestic market needed to purchase those cars, buses, and two-wheelers. Beijing’s end goal, however, has always been to expand beyond its own shores, supplying batteries to carmakers in the rest of the world.

Until now, CATL’s success has been a result of shrewd business and engineering decisions, combined with heavy doses of luck and government subsidies. But things are changing now that the Chinese government is reducing those subsidies, and how the company reacts could set the tone for the future of global battery and electric-vehicle manufacturing. A few months ago, CATL opened its doors to Quartz—the first Western publication to get a peek inside its sprawling headquarters and some of the world’s largest battery assembly factories.

An office with a vision

The first thing I noticed when I walked into Huang Shilin’s 20th floor office was the view. It was a gray day in November, and a thick fog rolled over the mountains in front of us, revealing a bay that opens into the East China Sea. For a moment, I forgot we were in the middle of an industrial park.

But the reality came rushing back when I walked up to the window and peered down at the construction sites dotted around the tower. Before I could ask, Huang, CATL’s 52-year-old co-founder and a recent addition to China’s growing billionaire class, started describing who was building what in this suburb of Ningde, a growing city of some 3 million people in Fujian province.

“SAIC is building a factory there,” he said, referring to Shanghai Automotive Industry Corporation, one of China’s largest makers of EVs. The carmaker will, of course, be acquiring batteries from CATL.

“And that’s where CATL is expanding,” he said, pointing to the roofless buildings across the bay. Other Chinese battery companies we talked to are surprised by CATL’s growth. Huang says he’s barely able to keep up with demand.

CATL’s story begins in the middle of the portable-devices boom. In 1999, Zeng Yuqun, a 31-year-old entrepreneur founded a company called ATL, which acquired technology licenses from US companies to make batteries for laptops and MP3 players (remember those?).

Within two years, it had produced batteries for 1 million devices and made its name as a reliable company. On the back off that success, in 2005, it was acquired by TDK, the Japanese firm probably best known for its cassette tapes and recordable CDs. Zeng and his second-in-command Huang decided to stay. TDK added Japanese discipline to ATL’s manufacturing process and expanded its lithium-ion battery market to the newest cash cow: smartphones.

Within years, ATL would go on to supply batteries to both Samsung and Apple. In the meantime, starting in 2006, Huang began fielding queries about batteries for electric cars.

The earliest request came from Reva, an Indian car company. At the time, it was making the G-Wiz, two-seater electric car, powered by lead-acid batteries, which had a top speed of about 40 kmph (25 mph), a range of 80 km, and took many hours to charge. Reva was looking for a company to supply lithium-ion batteries, which would increase the car’s speed and range, and enable faster charging.

The lithium-ion batteries found inside EVs are quite different from those in portable devices. You can’t simply put hundreds of phone batteries in an electric car, because vehicles need batteries that can pump out electrons at a much faster rate than those needed by devices.

So Huang and Zeng created a research department within ATL to develop a solution, and began acquiring technology licenses from the US they believed would help them come up with a battery to power electric cars. Apart from perhaps BYD, no other Chinese company at the time was buying up licenses or investing millions of dollars into early-stage car-battery R&D in this way.

Critics often accuse Chinese companies of stealing or copying from foreign firms. With their own robust R&D efforts, BYD and ATL broke that mold, and set the stage for Chinese domination of what could be one of the most important sectors of manufacturing in the 21st century.

The lucky break

By 2008, ATL had something to show for its effort. That year, the Chinese government rolled out a demo fleet of electric buses at the Beijing Olympics—some of which were powered by the company’s batteries.

The electric-bus demo fleet was the start of the government’s plan to push for the electrification of transport. It would cut deadly particulate pollution by reducing the amount of exhaust coming out of tailpipes of gas-powered cars, whose numbers were growing at unprecedented rates. The country was about to overtake the US as the world’s largest car market, and the Chinese government was under pressure from citizens and global media to do something about its smoggy skies. In 2009, the Chinese government launched the “Ten Cities, Thousand Vehicles” program, with the goal of deploying 1,000 electric vehicles in 10 of its largest cities.

Huang and Zeng sensed an opportunity. In 2011, they spun out ATL’s electric-car battery business into CATL.

Over the next 10 years, the Chinese government employed a carrot-and-stick method to push for the adoption of EVs. The subsidies—one of the biggest carrots—were generous, sometimes up to a third of the cost of a new electric vehicle. Car companies got tax breaks or cheap land to build factories. Then there was the stick: Many city governments started restricting the number of gas-powered cars that could be registered. When demand exceeded supply, which it always did, some city governments created a lottery system: In Beijing just 0.05% of applicants get approved for a gas-powered-car registration. Others instituted auctions: the winning bids for Shanghai’s licenses have recently averaged about $14,000—sometimes more than the cost of the car itself.

The upshot: In 2011, some 1,000 electric cars were sold in China. In 2018, Chinese customers bought 1 million electric cars—more than the rest of the world combined that year. The same year Zeng and Huang became billionaires on the back off CATL’s public listing.

The decade-long electrification strategy sent a clear signal to global carmakers that, to compete in the Chinese market, they would need to manufacture electric models. But Beijing set one, huge condition: only cars running on batteries bought from a Chinese supplier would qualify for government subsidies.

Around 2010, BMW and its joint-venture partner Brilliance, a Chinese automaker, began to look for a domestic battery supplier, so they could make EVs that would be eligible for government subsidies. The only two Chinese contenders with decent reputations available at the time were CATL and BYD. But it turned out that BYD, founded in 1995 by a battery engineer, wasn’t interested in supplying batteries to other companies. The company had its own car manufacturing setup and preferred to keep the batteries for itself. So BMW chose to work with CATL.

In 2013, BMW-Brilliance launched the all-electric Zinoro. It was based on the design of the X1, BMW’s subcompact SUV, and used CATL batteries. The electric SUV did well enough that BMW started manufacturing a plug-in hybrid version, also using CATL batteries.

Unlike AA or AAA batteries, which are essentially the same no matter who makes them, electric-car batteries need to be custom-made for different car models. That requires engineers from the carmaker to work with those from the battery company, exchanging ideas, standards, and processes. As it worked with BMW on Zinoro, CATL added German engineering chops to its skillset.

“We have learned a lot from BMW, and now we have become one of the top battery manufacturers globally,” Zeng said at the 2016 Zinoro plug-in hybrid launch event. “The high standards and demands from BMW have helped us to grow fast.”

Three years later, CATL would break ground on Germany’s first automotive-battery factory, beating the revered German auto industry to the punch.

How to make lithium-ion batteries

After leaving Huang’s office, I got a tour of one of the battery production lines. With its white walls and long corridors, it felt more like entering a hospital ward than a battery factory. At the entrance, we had to wear shoe covers to prevent outside dust from entering the factory. We also had to relinquish our smartphones; we would not be allowed to take any pictures.

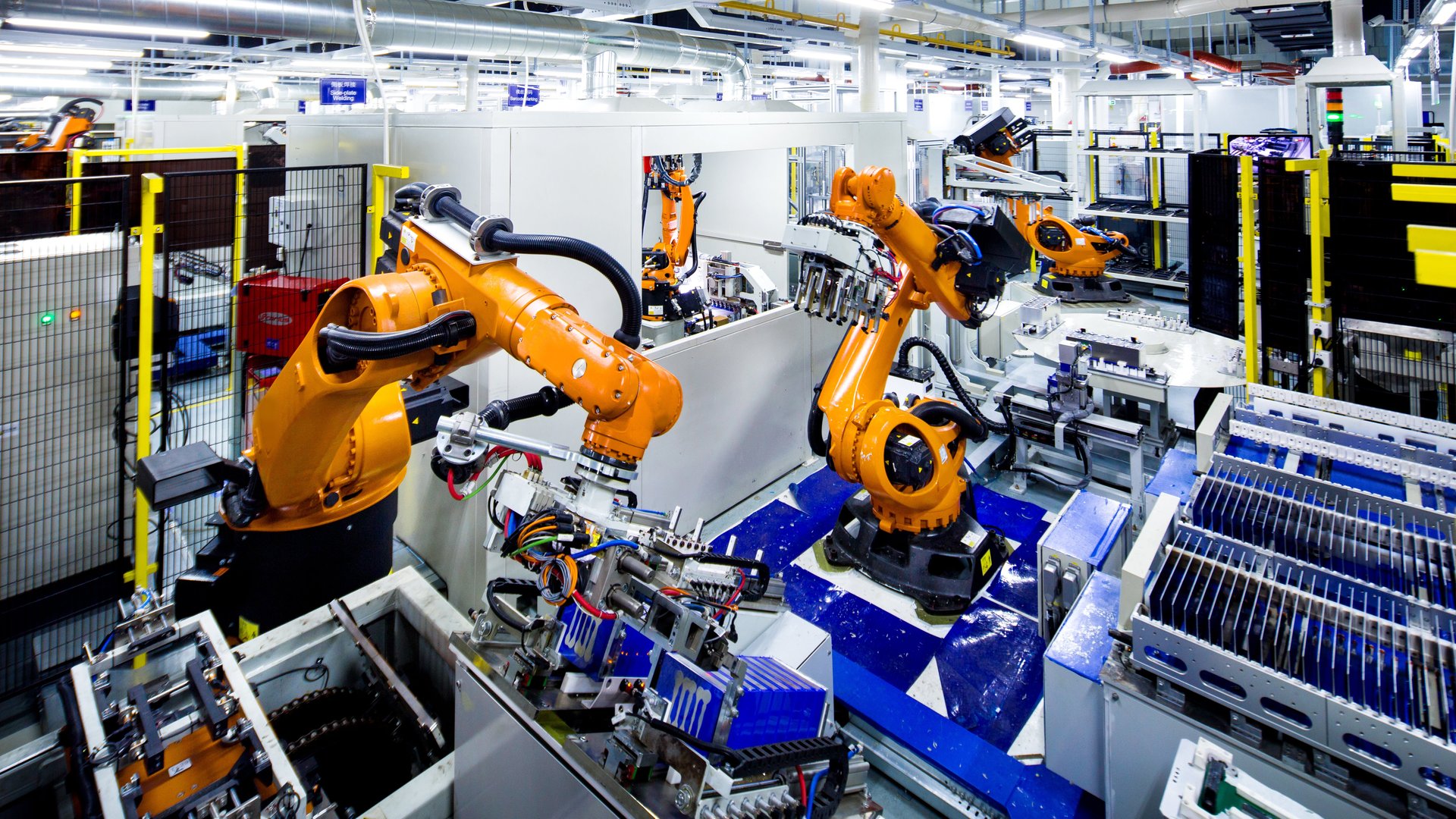

On one side of the corridor were windows through which we could see the battery-production floor, where there seemed to be an equal number of humans and robots. The humans were covered from head to toe: shower cap, lab coat, gloves, and shoe covers. The robots did their jobs naked. The humans spent most of their time observing machines or computers. The robots did the heavy lifting and moving of different components between machine lines and elevators.

All batteries have five components: two electrodes (anode and cathode), a separator (preventing the electrodes from getting shorted), an electrolyte to allow for the charge to flow from one electrode to another, and a case to protect all the components.

The process of making a lithium-ion battery begins with mixing solvents—liquids that can be easily evaporated—with powdered electrode materials, creating a slurry.

CATL primarily uses two types of cathodes: lithium iron phosphate (LFP) for electric buses and nickel manganese cobalt oxides (NMC) for electric cars. NMC packs more energy in less space and is thus used in smaller vehicles, but it is more expensive than LFP. In both cases, the anodes are made of graphite (sometimes mixed with a little bit of silicon).

Once the slurries are made, they’re painted on sheets of metal: copper for the graphite-coated anode and aluminum for the LFP- or NMC-coated cathode. The sheets go through a hot oven, which dries out the solvent and allows the powder to adhere to the metal sheet.

What happens next depends on the shape of the battery. Some are cylindrical cells (used by Tesla), others are pouch cells (used by Jaguar), and still others are prismatic cells (used by BMW). The next steps are to combine the electrodes, the separator, and the casing; charge the battery for the first time; and then seal it and test it for any defects. But the job is still not done.

The next step, which involves combining many cells into a battery pack, is where CATL’s engineers need to work with the carmaker’s engineers. This is where knowledge and skills are exchanged between the two teams; each and every car model gets a battery pack uniquely designed for it.

To build a car battery pack for the BMW i3, for instance, some 90 prismatic cells are connected to each other. The batteries are arranged to fit perfectly into the car’s chassis. The connected prismatic cells are operated by a battery-management system, which can measure the state of charge and the health of each battery. The system is also equipped with heat-management systems, which kick in to help batteries charge or discharge at a safe temperature.

CATL has become one of the best in the field at managing this complex and delicate production process, and today it has a long list of carmakers as customers, from German brands like BMW and VW to Asian companies like Honda and Nissan. In just a few short years, CATL combined Japanese discipline, German engineering, and Chinese entrepreneurship to become one of the most desirable battery manufacturers in the world.

“Technically they are probably a tad behind the big three [Panasonic, Samsung SDI, and LG Chem],” Menahem Anderman, president of Total Battery Consulting, told Bloomberg in 2018. “But considering how fast they have been moving, it’s reasonable to assume that in two to three years they’ll have a technically similar product.”

A pig with wings

In April 2017, a year before CATL’s public offering, Zeng sent an internal email laying out his vision for the company. “What happens after the typhoon passes?” he asked. “Can a pig really fly?”

He was referring to a Chinese allegory: “When the typhoon comes, the pig will fly.” The pig, in this case, was the company; the strong winds of the typhoon were government subsidies; and the worry was that when the subsidies (aka the typhoon) dissipated, the company (aka the pig) would no longer be able to fly.

Zeng’s email was prescient. On March 26, the Chinese government announced it will lower the subsidies it offers to electric vehicles with a complete phaseout likely to happen in 2020.

Zeng’s message to his employees was to not get complacent. As the leader of CATL, he had been preparing for the end of subsidies, in part by diversifying the company’s revenue sources. While China is the world’s largest electric-car market, sales in Europe and the US are picking up. CATL is banking on orders from other parts of the world to fill the gaps created if sales in China slow as subsidies disappear.

Over the last few years, CATL has established offices in France, Germany, Canada, Japan, and the US. In 2017, it acquired Finland’s Valmet Automotive, which supplies parts, including batteries, to the likes of Mercedes-Benz, Porsche, and Lamborghini. And last month it began construction of a gigafactory in Erfurt, Germany.

At the same time, to stay ahead of the pack, CATL is making large investments in research. Its brochure to investors before its public offering in June 2018 said it spent 11% of its revenue on R&D in 2017. BYD, CATL’s largest Chinese competitor, spends less than 6% of its revenue on research.

CATL is also starting to manufacture and sell lithium-ion batteries for energy storage on the grid and for EV charging. Under Huang’s leadership, CATL has developed shipping-container sized battery units with an energy capacity of up to 2 MWh that can do both. When an electric car needs to recharge, the batteries can provide high-speed charging without adding demand on the grid. When there are no cars charging, the batteries act as storage for the grid, by squirreling away solar and wind power for use when the sun doesn’t shine and the wind doesn’t blow.

A CATL spokesperson said it has deployed a few units for testing, but wouldn’t give the exact number. Huang is convinced that the use of lithium-ion batteries for energy storage will see the kind of rapid growth in demand seen in the EV market.

Even if Huang is wrong, there’s no denying CATL’s remarkable achievements. The company has alone put China on the world’s lithium-ion battery map. If CATL’s aggressive projections come true, by 2021 China will be supplying 70% of the world’s lithium-ion batteries. After conquering the markets for solar panels and wind turbines, with CATL’s help, China will have conquered yet another crucial 21st century technology.