As US communities resist ICE, private prison companies are cashing in

Local governments are rebelling against the Trump administration’s immigration crackdown by refusing to hold the growing number of undocumented immigrants in its custody.

Local governments are rebelling against the Trump administration’s immigration crackdown by refusing to hold the growing number of undocumented immigrants in its custody.

From California to Michigan, city councils and county officials are cancelling contracts with US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), which rents bed space from local, county, or state-owned jails across the country. It also has hundreds of contracts with private companies to run immigration detention facilities.

The pushback doesn’t change things much for immigrants, though. The number of undocumented detainees is at a record high of 50,000, according to the latest ICE data.

If anything, local resistance is creating more opportunities for private corrections companies, and in the age of Donald Trump, business is booming.

Municipalities say no

ICE detainees can end up in local jails when the immigration enforcement agency asks local authorities to keep undocumented inmates locked up past their sentences, and pays for each extra night, or when a local jail leases space to ICE or to a private company contracted by ICE.

The majority of detainees in ICE custody—four out of five—have no criminal record or committed a minor offense, such as a traffic violation, according to data analyzed by the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) at Syracuse University.

Under growing pressure from immigrant advocates, local communities are starting to say no to ICE. Since last summer, at least five California counties have terminated detention agreements with ICE. “Municipalities are feeling pressure from their constituents not to enter into these dirty contracts, which is a trend we are seeing,” Liz Martinez of Freedom for Immigrants, a West Coast advocacy group, tells Quartz.

The resistance is also happening in states that went for Trump. At least four counties in Michigan have severed ties with ICE. Kent County, where Grand Rapids is located, ended its cooperation with ICE in January, after Jilmar Ramos-Gomez, a US Marine Corps veteran with PTSD, was mistakenly detained and held for deportation for three days before a lawyer was able to get him out. The following month, Michigan governor Gretchen Whitmer, a Democrat, canceled the sale of a former state correctional facility that was to be transformed into a privately-run ICE detention center.

From local to private

There are signs that some of the business being turned down by local entities is being picked up by private companies. Last June, Atlanta’s city jail stopped accepting ICE detainees by executive order of mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms.

“I, like many others, have been horrified watching the impact of President Trump’s zero tolerance immigration policy on children and families,” Bottoms said in a statement. “My personal angst has been compounded by the City of Atlanta’s long-standing agreement with the U.S. Marshal’s Office to house ICE detainees in our City jail.”

At the time, Bottoms said she worried that immigrants would end up in a more precarious situation if ICE put them in private facilities instead, but added the city couldn’t in good conscience continue holding them. In fact, ICE is now using a private facility elsewhere in the state and managed by the GEO Group, one of the two biggest private prison companies in the country.

In Williamson County, Texas, county commissioners voted last year to let their contract with ICE expire. The county served as an intermediary between ICE and CoreCivic, which ran a controversial detention center that houses immigrant women and children. But the facility remains open, as ICE simply circumvented the county and began working directly with CoreCivic.

The same thing is happening now in California, where state law forbids local governments from signing new agreements with ICE or expanding existing ones. In Adelanto, a high-desert town in Southern California where local officials canceled a contract under which GEO was holding ICE detainees at a county jail, private detention may actually expand under a new deal with ICE that cuts the county out of the equation altogether.

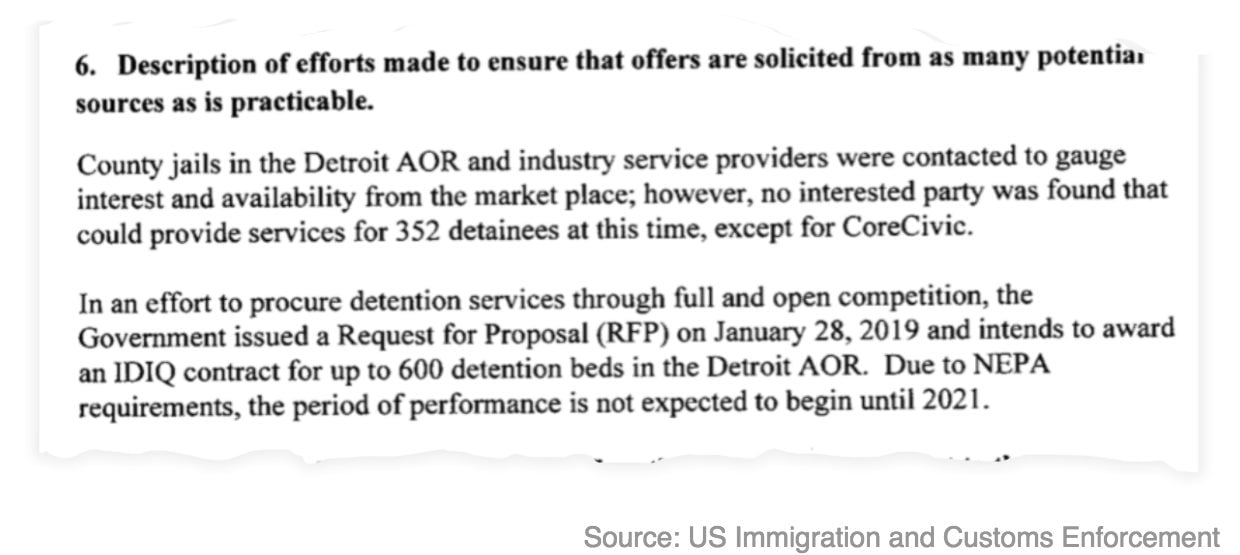

The reluctance of local governments to work with ICE means private companies sometimes have no competition. When ICE opened up bids to house 352 detainees in the Detroit area, CoreCivic, which currently holds the contract, was the only one to show any interest.

“County jails in the Detroit AOR (Area of Responsibility) and industry service providers were contacted to gauge interest and availability from the marketplace; however, no interested party was found that could provide services for 352 detainees at this time, except for CoreCivic,” says an ICE contract extension posted to a federal database.

CoreCivic spokesperson Amanda Gilchrist referred questions about the contract to ICE. ICE did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

A growing industry

Private prisons began to emerge in the mid-1980s, and were fully entrenched in the American penal system by the mid-90s, Lauren-Brooke Eisen, a private prison expert at NYU law school’s Brennan Center for Justice, tells Quartz.

The Obama administration reduced their use—GEO Group and CoreCivic stock dropped 39% and 35% the day the Justice Department announced the US Bureau of Prisons would no longer make deals with private corrections companies, although it exempted ICE from the new policy—but in the age of Trump, private immigration jails are thriving.

In 2018, federal spending on immigration detention and processing reached $7.4 billion, compared with total expenditures of $5.3 billion four years earlier. Over that period, CoreCivic’s take rose by $85 million; GEO’s went up by $121 million, according to an analysis of contract data by Bloomberg Government.

Both companies have faced numerous allegations of safety and human rights violations at their facilities, and as business grows, private prison operators might expect increasing legal and political pressure from activists. For example, CoreCivic is currently embroiled in a class-action lawsuit over a work program at one of its facilities that allegedly paid detainees $1 to $2 per day to clean bathrooms, prepare and serve meals, and do laundry and clerical work.

For years, city and county governments didn’t mind taking the revenue from these deals with ICE and private prisons, says R. Andrew Free, a Nashville-based immigration and civil rights attorney. But these days, they’re becoming more aware of the liabilities involved.

“What we see now is a market and accountability adjustment,” says Free. “Once you put the risk these places carry back on the books, that sweetheart deal doesn’t look so sweet anymore.”

This article has been updated with additional detail about the Obama administration’s private prison policy.