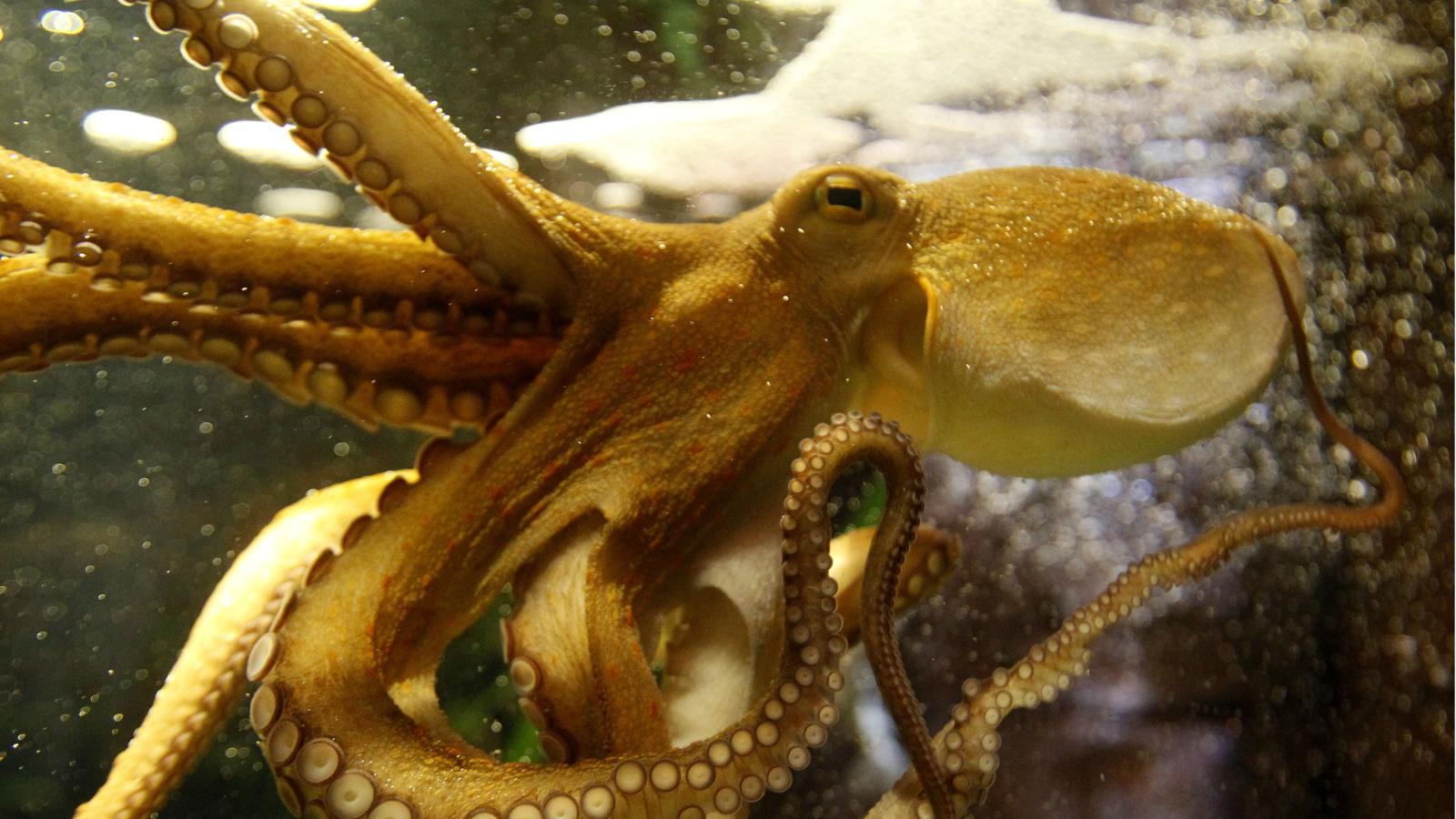

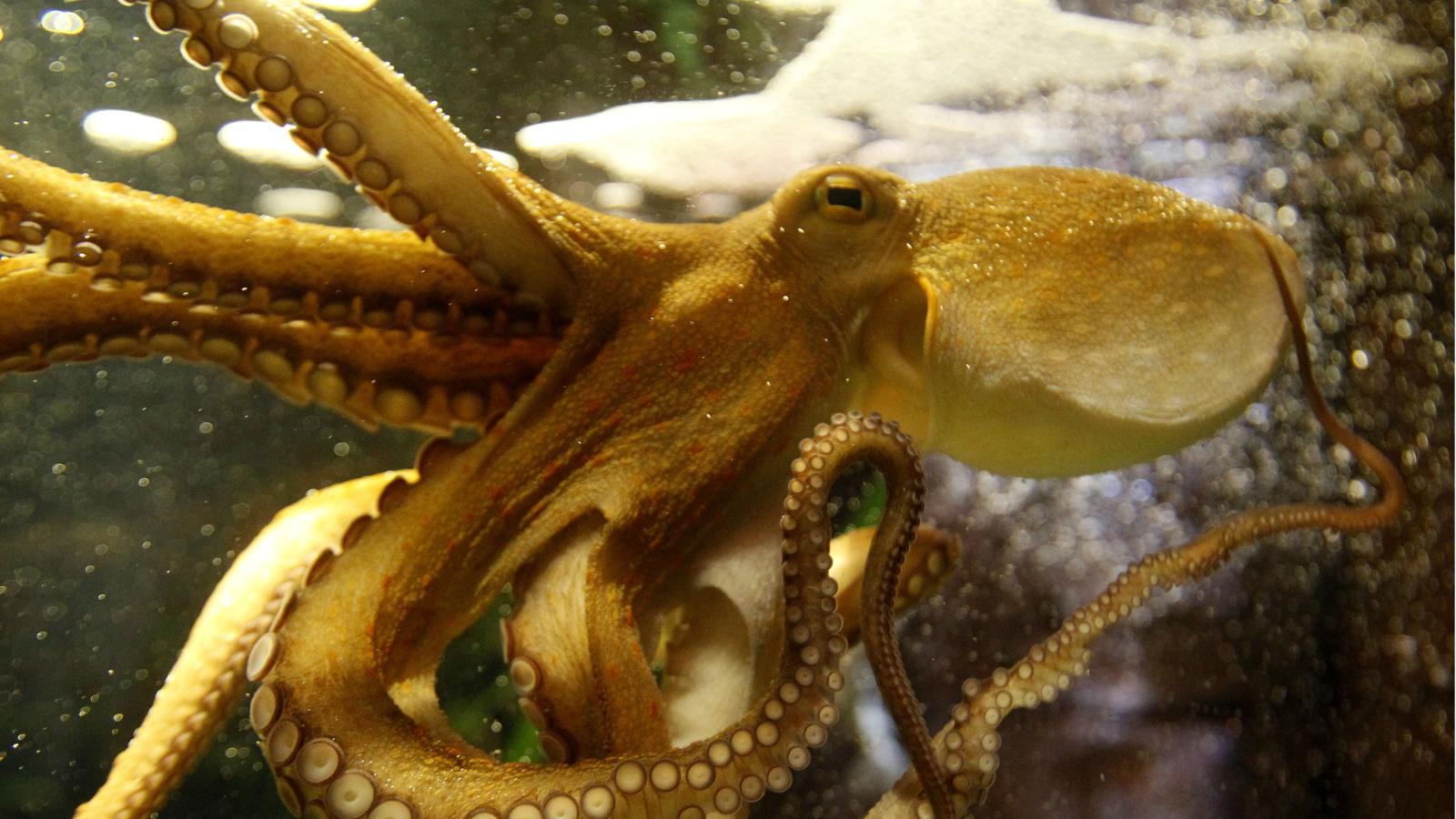

Octopus farming will soon be the norm. Marine scientists say this isn’t a good thing

The arrival of octopus farms is fast approaching. So far, the animals have escaped farming because they are extremely difficult to feed soon after being born, and have a low survival rate. But technological advances and experimentation are making it possible. A Japanese seafood company hatched octopus eggs in 2017 and expects to see farmed octopus for sale by next year; a Mexican farm has reportedly farmed octopus, and farms in Spain and China are also getting in on the business.

The arrival of octopus farms is fast approaching. So far, the animals have escaped farming because they are extremely difficult to feed soon after being born, and have a low survival rate. But technological advances and experimentation are making it possible. A Japanese seafood company hatched octopus eggs in 2017 and expects to see farmed octopus for sale by next year; a Mexican farm has reportedly farmed octopus, and farms in Spain and China are also getting in on the business.

This is not worth celebrating, according to four marine researchers who presented their argument in the Winter 2019 edition of Issues of Science and Technology. For one thing, they note, octopuses are carnivorous and so farming them increases pressure on the ecosystem, because farmers have to catch a huge amount of wild fish to feed them. Octopus farming “would increase, not alleviate, pressure on wild aquatic animals,” they write. “Octopuses have a food conversion rate of at least 3:1, meaning that the weight of feed necessary to sustain them is about three times the weight of the animal.”

But there’s also an issue unique to octopuses: that they’re incredibly clever. “One study found that octopuses retained knowledge of how to open a screw-top jar for at least five months,” write the marine researchers. “They are also capable of mastering complex aquascapes, conducting extensive foraging trips, and using visual landmarks to navigate.” Octopuses are considered the only definitively conscious invertebrate, meaning they’re the most developed animal that’s least similar to humans and, as such, the closest thing to an alien on this planet.

Farming octopuses likely means they’ll be kept in small containers with monotonous lives that do not satisfy their need for mental stimulation and exploration. Plus, note the researchers, farming octopuses so far is linked with increased aggression, parasitic infection, and high mortality rates.

Of course, the argument not to farm octopuses raises the question: Why farm other animals? Salmon may be less intelligent than octopuses, but chances are they still enjoy frolicking in the streams and deserve an enjoyable lifestyle. It would take considerable effort to stop the practices of long-established types of farming (such as for sheep, which started 9,000 years ago, say the researchers). Before we start octopus farming, we at least have the chance to reconsider: Is this really the right way to treat another animal?