Dolphins’ complex clitorises are the key to understanding their sex lives

There’s an oft-cited factoid that dolphins are, along with humans, one of the few animals that have sex for pleasure. It’s based on scientific observations of dolphins copulating year-round even though females are only fertile for a few months of the year. But of course, because of the pesky animal-human language barrier, no one’s ever been able to actually ask a dolphin about sexual pleasure.

There’s an oft-cited factoid that dolphins are, along with humans, one of the few animals that have sex for pleasure. It’s based on scientific observations of dolphins copulating year-round even though females are only fertile for a few months of the year. But of course, because of the pesky animal-human language barrier, no one’s ever been able to actually ask a dolphin about sexual pleasure.

The structure of female dolphin reproductive anatomy, though, can speak for itself.

At the Experimental Biology conference held April 6-7 in Orlando, Florida, marine mammal researcher Dara Orbach presented preliminary findings from one of the first studies to examine bottlenose dolphin clitorises. Orbach and her co-author, Patricia Brennan, both from Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts, were surprised to find dolphin clitorises have several bundles of nerves, similar to human clitorises. Because the clitoris is accessible during any kind of position a male would take during copulation, says Orbach, it’s highly likely it plays a role in pleasure.

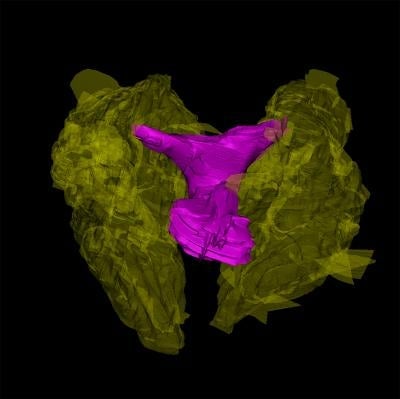

Orbach and Brennan examined clitorises from 11 dolphins that had died of natural causes and washed ashore. The sample size is relatively small, but crucially, it included dolphins of all ages, from calves to adults. They looked at the clitoris anatomy as a whole, and then conducted other experiments to identify each type of tissue present in the structure. Across all ages, dolphin clitorises had erectile tissue, blood vessels, muscles, and nerve bundles. They also contained a hard, cartilage-like tissue called elastin, which Orbach says help keeps the blood flow concentrated in the erectile tissue.

Although these preliminary findings don’t definitively prove that dolphin reproduction can also be for pleasure, they do add evidence to the argument that for dolphins, sex isn’t entirely about reproduction. Sex can serve several different functions, like social learning or establishing dominant hierarchies, says Orbach. Male calves frequently mate with their mothers, and “a lot of the [dolphin] mating we see in the wild is homosexual mating,” she says. “It could be males establishing who’s the leader in the group.”

Before Orbach and Brennan submit the study to a peer-reviewed journal, they’re waiting to find a few more dolphins that died of natural causes to add to their sample size. Examining dolphins shortly after death could confirm that the cells they observed are, in fact, nerve bundles. The 11 dolphin clitorises examined so far are part of a collection of over 300 reproductive tracts of dolphins, whales, and porpoises that reside in the Mount Holyoke College necropsy facilities. These animals had beached across the US, and then been found and collected by local stranding groups and shipped to the lab.

Historically, female reproductive anatomy in animals has been widely understudied. Most animal reproduction research has been focused on the variations among penis morphology, at least partly because the penis, as an external organ, is easier to access. As scientists have started studying vaginal morphology in the past 10 years or so, it’s become clear that vaginas are equally diverse. For example, unlike human vaginas, whale, dolphin, and porpoise vaginas all have extra folding in the reproductive tract, making them unique among members of different species. Why this folding would take place is a mystery, but Orbach believes it’s not arbitrary. “If you have such diversity in structure, you’d expect it to have a function,” says Orbach.