British scientists have turned to crowdsourcing to better understand climate change

Scientists have amply documented that climate change is a global phenomenon, caused by human activity. But there is still much to learn about how this affects weather patterns at a more local level. One group of scientists in the UK has turned to crowdsourcing to construct a historical record of local weather conditions starting in the 1860s, which could help better understand the impact that climate change will have on specific places in the future.

Scientists have amply documented that climate change is a global phenomenon, caused by human activity. But there is still much to learn about how this affects weather patterns at a more local level. One group of scientists in the UK has turned to crowdsourcing to construct a historical record of local weather conditions starting in the 1860s, which could help better understand the impact that climate change will have on specific places in the future.

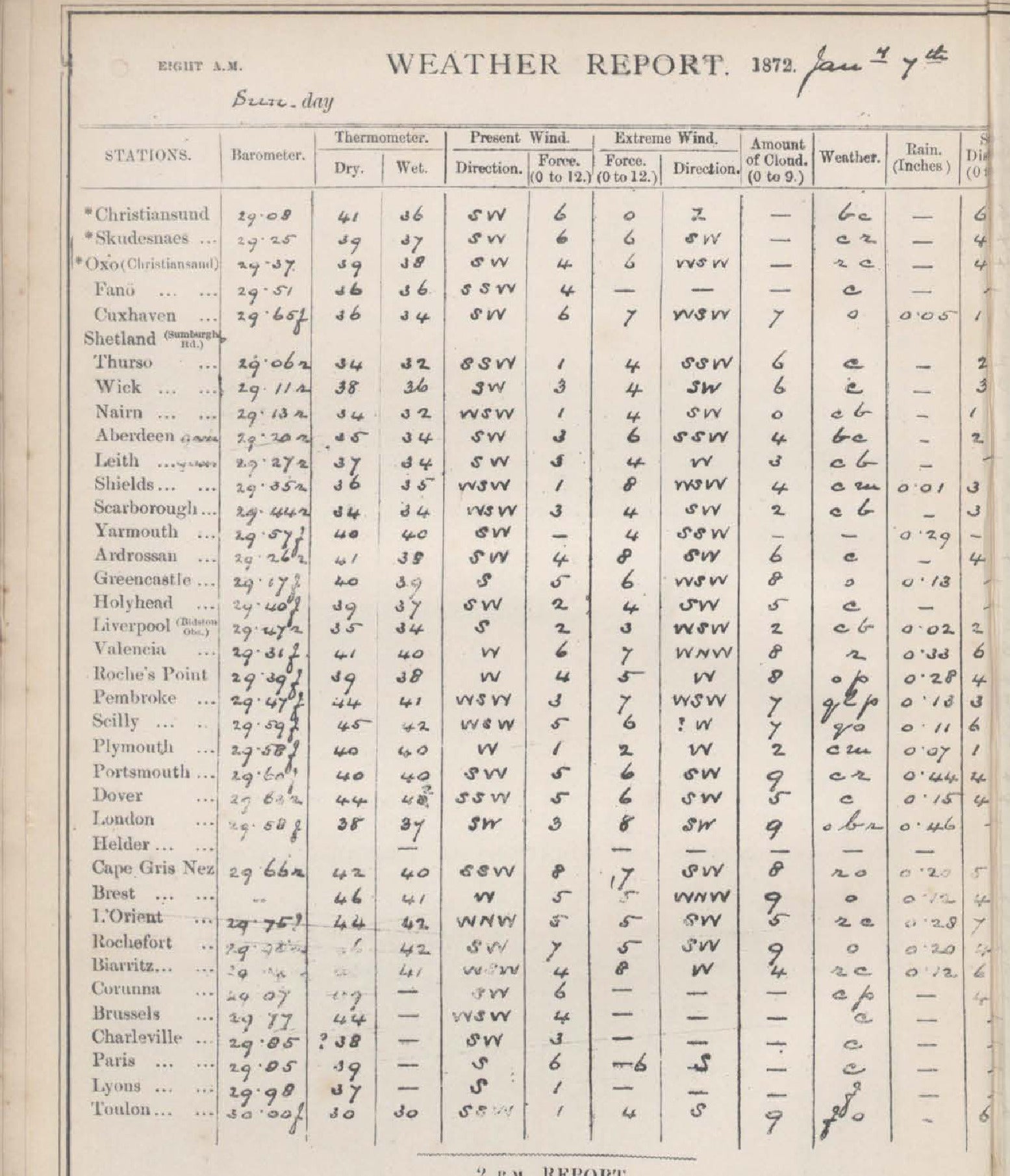

Researchers at the University of Reading launched the latest iteration of a project called Weather Rescue last month, which has since 2017 called on volunteers to transcribe millions of handwritten weather recordings from around the UK and northwest Europe. Thousands of people have signed up on crowdsourcing research site Zooniverse to pore over scans of dusty archives. The aim is to use past measurements to help understand current weather patterns.

“If we manage it, this will be the first time that climate scientists and meteorologists from around the globe will have had access to the raw data,” the project’s Zooniverse page wrote.

One goal of Weather Rescue is to look at the risk floods pose to the UK, which the team says is the biggest consequence of climate change to the country. An earlier iteration of the project found that October 1903 was the UK’s wettest month on record. “Because we’ve had 100 years since then and the atmosphere has warmed up, we’d probably get more rain if those same weather patterns occurred today,” said Ed Hawkins, who is leading the project team. “And so, we can say to government… can your flood defenses deal with that amount of water? These are real questions that policymakers and planners need to understand the answers to.”

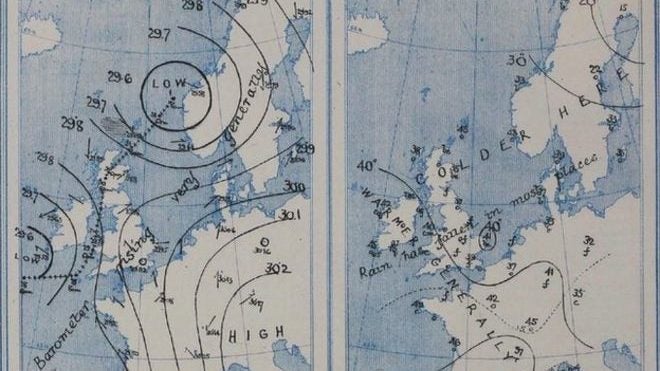

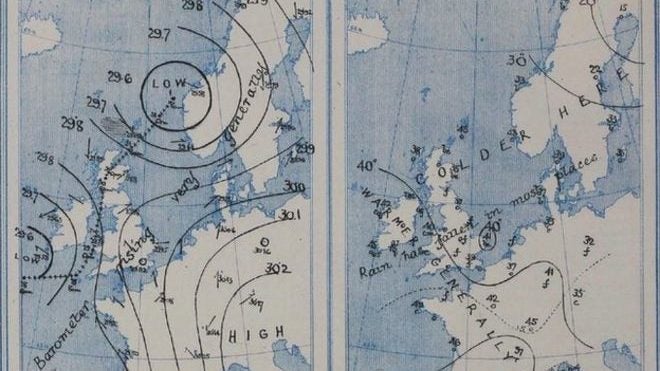

The UK was the first country to systematically document weather observations. In 1854, the UK Met Office was launched by vice-admiral Robert FitzRoy, who already had a noteworthy career as captain of the HMS Beagle that sailed Charles Darwin around the world. The idea behind the new government department was to understand the weather better, with the aim of averting disasters and speeding up shipping, which was crucial to the UK’s maritime economy.

When a major storm struck in 1859, sinking a Royal Charter ship stashed with gold and 450 people onboard, FitzRoy decided to think more deeply about predicting the weather. He set up a network of observation sites at coastal ports across the UK, with staff trained to take daily temperature, pressure, and rainfall measurements, and then telegraph them back to London. The first storm warning was given in 1861—it was ignored, leading to shipwrecks and deaths. The Times newspaper soon after began printing the forecast, the first such public weather prognostications in the world.

The Weather Rescue project’s most recent iteration has transcribed about 250,000 unique weather observations, completing the period of 1861-71. That’s about 10 person-years of transcribing in just a few months. “We would never be able to get funding to employ someone for 10 years… so it is a very cheap and efficient way. And people love it,” Hawkins said.

Volunteers are now looking at the 1870s. The project’s researchers have scanned copies of all the Times’ daily weather reports from 1861 onward, and so many additional decades of observations are waiting to be transcribed. Doing so will improve the accessibility of historical records and help shed light on the UK’s historical weather patterns.

That’s good news for Brits who, according to the project’s researchers, spend eight hours a week checking, talking, or thinking about the weather.