The ethical and legal implications of having a universal genetic database

The idea of a universal genetic database can sound like the stuff of dystopian sci-fi. If the government had access to your entire, uniquely-identifying genetic code, it could follow every move you make based on traces of DNA you leave behind. It could be privy to all kinds of private information about your health. It could be a biological Big Brother.

The idea of a universal genetic database can sound like the stuff of dystopian sci-fi. If the government had access to your entire, uniquely-identifying genetic code, it could follow every move you make based on traces of DNA you leave behind. It could be privy to all kinds of private information about your health. It could be a biological Big Brother.

This isn’t far from reality. Right now, US law enforcement has what amounts to nearly open access to many Americans’ genetic data, thanks to the popularity of direct-to-consumer (DTC) genetic tests.

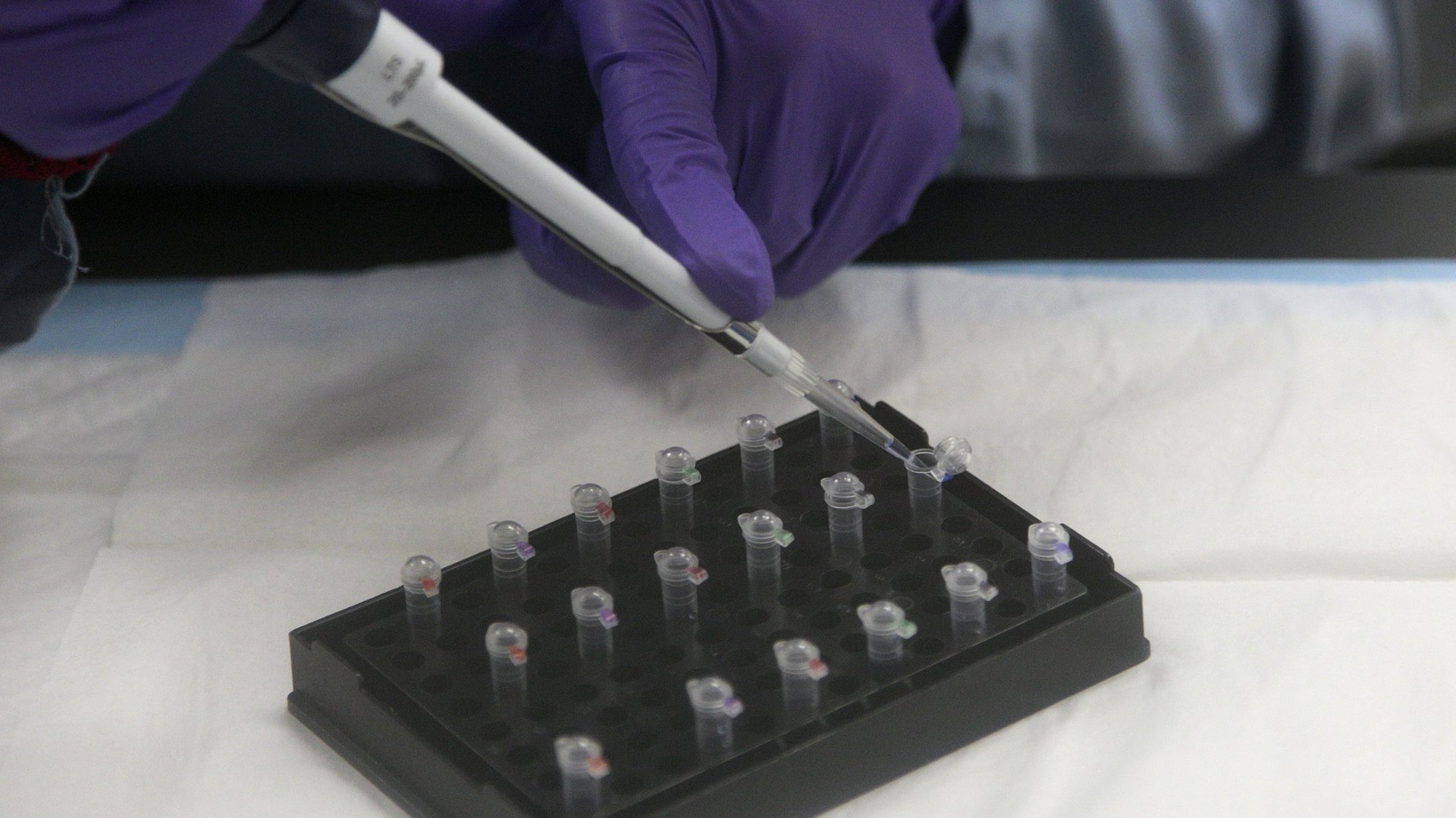

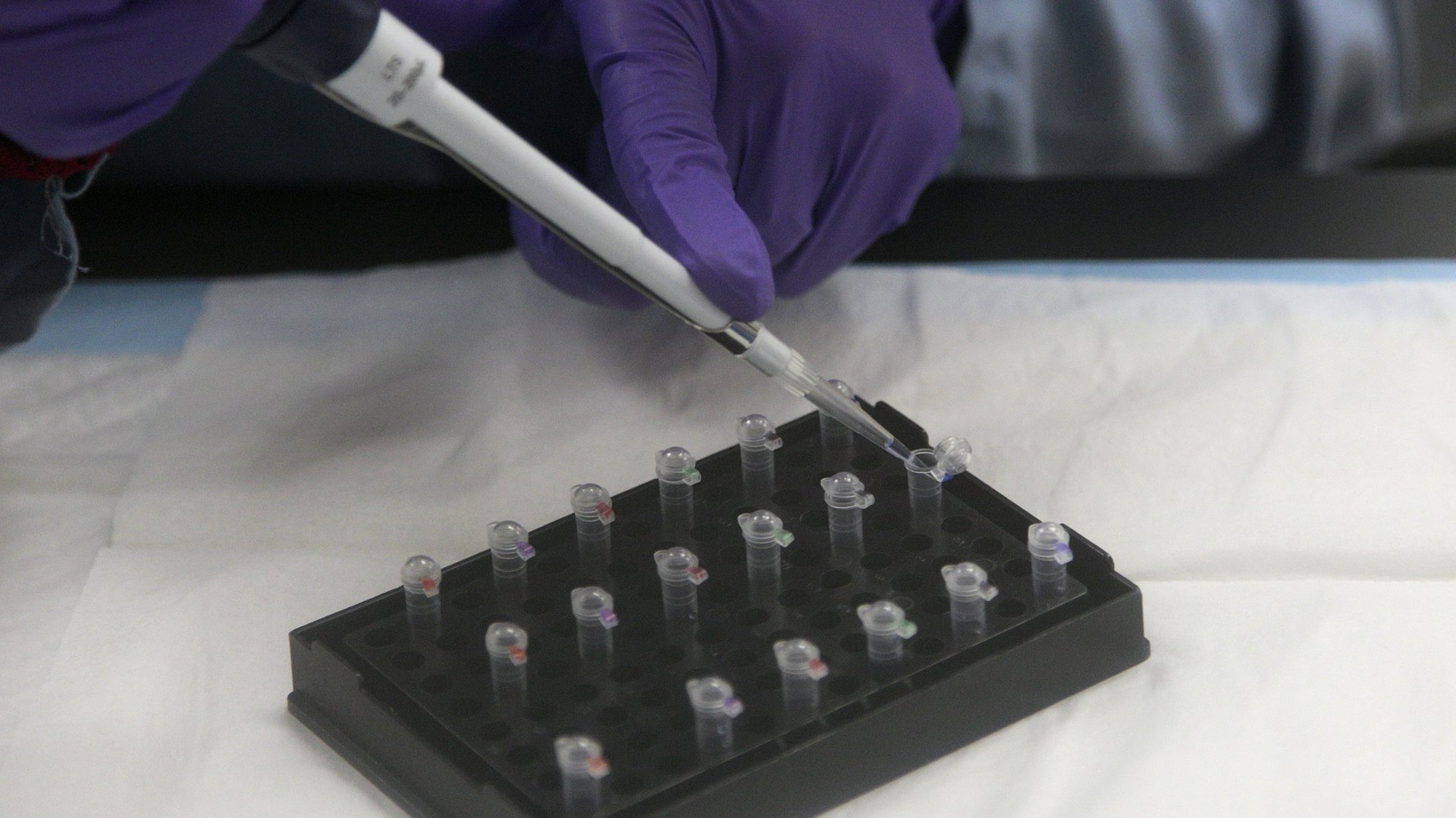

DNA had a place in US law enforcement starting in the 1980s, but it wasn’t until 1990 that the FBI started looking at ways to create genetics-based forensic databases to solve violent crimes. Then, in 1994, the passage of the DNA Information Act cleared the way for the agency to develop a national database of criminal DNA.

Over the years, local, state, and federal law enforcement agents collected the genetic data from Americans all over the country who came in contact with the law. As of February 2019, US law enforcement had gathered genetic information from roughly 18 million individuals. The problem with these data, though, is that they come only from people who have had previous run-ins with the law. And, due to deeply systemic biases, that means the database is comprised of genetic information belonging disproportionately to people of color. But that’s only a starting point for how many people’s DNA the law can access in the US.

In 2018, US law enforcement learned that the Virginia-based biotech company Parabon NaNoLabs had started to dabble in a field called forensic genealogy: uploading samples from crime scenes to public genetic databases in the hopes of turning up a match. Law-enforcing agencies have taken advantage of these databases ever since. Most famously, police found and arrested Joseph James DeAngelo, known as the “Golden State Killer,” by uploading genetic evidence found from decades-old crime scenes to GEDMatch, a free website created by two amateur genetic genealogists in 2010, and which had roughly a million users as of last year. Police pretended to be just another customer looking for family members on GEDMatch; sure enough, the service led them to DeAngelo. Since then, US law enforcement has solved dozens of cold cases using publicly available DNA.

GEDMatch is just a small pond in a sea of genetic data available to authorities. Earlier this year, Buzzfeed reporters discovered that US federal law enforcement had been working with the company FamilyTreeDNA. The company quickly added an option for customers to opt-out of sharing their information with the FBI last month. A new television ad campaign scheduled to air in San Diego this spring, however, encourages users to continue to allow law enforcement to have access to their genetic data.

Other private companies, like 23andMe and AncestryDNA, have said they will not work with law enforcement. But legally, they could still be compelled to give up their data to the law in the future. As of January 2019, roughly 26 million people globally had taken some form of DTC genetic testing, the majority with Ancestry. It’s impossible to tell how much overlap there is between these 26 million people and the 18 million people in the US government’s official database, but it’s safe to say US law enforcement has at least 20 million Americans’ DNA on record.

Given how disquieting that sounds, it will probably seem strange to learn that a group of lawyers and ethicists from Vanderbilt University in Tennessee published an opinion (paywall) in the journal Science arguing for a universal DNA database last year.

The point, though, wasn’t to advance a futuro-fascist agenda, but to highlight the many flaws of a system that already exists. The idea was to be provocative, says James Hazel, co-author of the paper and a postdoctoral fellow at the Vanderbilt University Medical School. But the thought experiment does lay bare the reality that law enforcement is severely under-regulated when it comes to access to genetic data.

Quartz spoke with Hazel about the ethical and legal implications of having a universal forensic database to replace law enforcement’s current genetic database and access to public and private databases. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Quartz: Why call for a universal forensic genetic database? That sounds like the plot of dystopian novel.

James Hazel: It does bring dystopian things to mind. We hope to spur debate and highlight the fact that additional regulation for law enforcement is needed, even if that is just restrictions on when and how law enforcement can access these resources.

Even if these restrictions fall short of a universal database, they’re desperately needed. Law enforcement already has potential access to the genetic information of a large segment of the population, either directly or through relatives. You can link to essentially anyone in the country using these long-range familial searches.

How does law enforcement currently access genetic material in public and private databases?

When you’re talking about direct-to-consumer genetic testing companies like 23andMe, really the only thing the government needs to compel disclosure is a subpoena, which is much easier to get than a warrant or even a court order. With a subpoena, you have to show that the information you’re seeking is relevant to an ongoing investigation, which is a much lower bar than having to articulate that you have probable cause to believe that the information you’re looking for is within the database and that a crime has been committed. Many subpoenas can be issued by an attorney without a court authorization.

Law enforcement doesn’t even need a subpoena to access data in public databases like GEDMatch, or utilize a company like FamilyTreeDNA to upload a sample of crime scene DNA while pretending to be an individual.

Is there a difference between what genetic information law enforcement can upload to public databases compared to what customers can upload?

It’s one thing to analyze DNA from a cheek swab or a tube of spit, but when you’re talking about crime scene samples, it’s a whole different game. These samples are degraded— there may be multiple individuals in the mixture—so analysis becomes much trickier and the process is more error prone, and you’re not even sure the profile you generated is from the suspect themselves. If that profile turns out to be someone that is innocent, you can’t really take that back. That profile has been analyzed and put out there on the internet.

If we were going to create a universal database of everyone’s genetic information for law enforcement purposes, what kinds of new measures would be needed to protect users’ privacy?

A central idea of our proposal is that these profiles would consist of a very limited genetic profile that would reveal significantly less information than [a person’s entire] genetic information. Also, we call for the destruction of the physical sample used to obtain the forensic profile such that you couldn’t perform further testing to get additional information out of that sample.

What would stop law enforcement from continuing to access private genetic databases if a universal database were established?

If you had a system that was truly universal—meaning everyone in the country would be in the database, including lawmakers, as well as their most important constituents—Congress would be much more likely to enact protections that aren’t currently there.

Given the potential for abuse, we argue that such a system would need to be hosted outside of the Department of Justice, maybe in a more neutral agency like the Department of Health and Human Services. We also propose using some emerging technologies to encrypt the data in a way that multiple entities would both be required to “turn the key” to unlock access to those records, and a warrant based on probable cause would be required to access that information, rather than simply a subpoena or court order.

You’ve estimated that it would cost some $15 billion to get the proposal started. Is that feasible?

Criminal activity causes a tremendous monetary drain on society. Some of the cost of existing databases would likely be offset by the increase in crime solving.

If recent efforts in Arizona are any indication, when a state tries to massively expand its databases outside of the context of arrestees or those convicted of crimes, there’s been a tremendous amount of pushback. So yes, certainly there would be hurdles to implementation.

[Editor’s note: In February of this year, Arizona lawmakers proposed a state senate bill that would require anyone who had to be fingerprinted for a job to also submit a DNA sample to a government database, which would, in theory, be used to solve crimes. After significant public outrage, the bill was amended until its initial intent was virtually erased. The version that passed is far narrower in scope, requiring only that law enforcement collect genetic information from rape kits to try to identify criminals.]

How could we improve genetic data privacy protection in the US?

Currently in the US, there’s little to no regulation of what information direct-to-consumer genetic testing companies need to provide to consumers about their genetic data practices. So really they’ve been left to self-regulate in terms of privacy policies.

I think it remains to be seen in terms of how it will be implemented, but the General Data Protection Regulation in Europe with its restrictions applied to genetic data certainly provide protections that are beyond those in the US.

[Editor’s note: The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) applies to any kind of personally identifying data, including genetic data. GDPR makes it easier for users to give and withdraw consent to sharing their data.]

We do have some laws, like the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act, that would mitigate the risks of discrimination in terms of employment and [health] insurance…but really we don’t have any comprehensive data privacy legislation like what was recently enacted in Europe.

Have you taken a direct-to-consumer genetic test?

So far I have not taken the leap. I will admit I can definitely see the appeal of testing with a company like 23andMe or wanting to explore your ancestry with a company like Ancestry. I just caution individuals that want to get this testing performed to make sure they take the added step of reading through the privacy policies and terms of service. They need a good picture of where their genetic data is going and how it’s being used, and what options they have to limit sharing or participate in research.