SpaceX blew up a Dragon spacecraft over the weekend

A SpaceX vehicle designed to carry astronauts to the International Space Station was destroyed during an engine test on April 20 at Cape Canaveral.

A SpaceX vehicle designed to carry astronauts to the International Space Station was destroyed during an engine test on April 20 at Cape Canaveral.

Thick, red-tinged smoke from the explosion was visible from nearby beaches, but no one was reported hurt in the accident or its aftermath. Detecting anomalies like this is precisely how engineers ensure the safety of the spacecraft and its future passengers.

Still, the destruction of the vehicle is likely to mean more delays for NASA’s $6.5 billion commercial crew program, which has Boeing and SpaceX racing to return human spaceflight to the United States. The space agency was still assessing the results of the test on April 22 and declined to comment immediately.

SpaceX engineers were preparing for an important demonstration, called a “pad abort test,” which would show that their Dragon spacecraft could use its own rocket motors to fly to safety if the large booster rocket it rides into orbit is in danger. A video, purportedly leaked from SpaceX and which briefly circulated on the internet before being pulled down, showed the spacecraft mounted on a test stand and then bursting into flames.

That test was among the final milestones that would allow the company to fly a crewed mission perhaps as soon the summer. That critical mission will be delayed, likely for months, as NASA and SpaceX seek to discover what went wrong with the rocket motor and led to its explosive failure.

Like many similar designs, the Dragon engines rely on volatile chemicals called hypergolics, which combust when combined. Though this allows for simpler and more reliable engines, managing the propellants can be a problem. Boeing learned a similar lesson last year as it prepped its Starliner spacecraft for a pad abort test and discovered the toxic fuel was leaking.

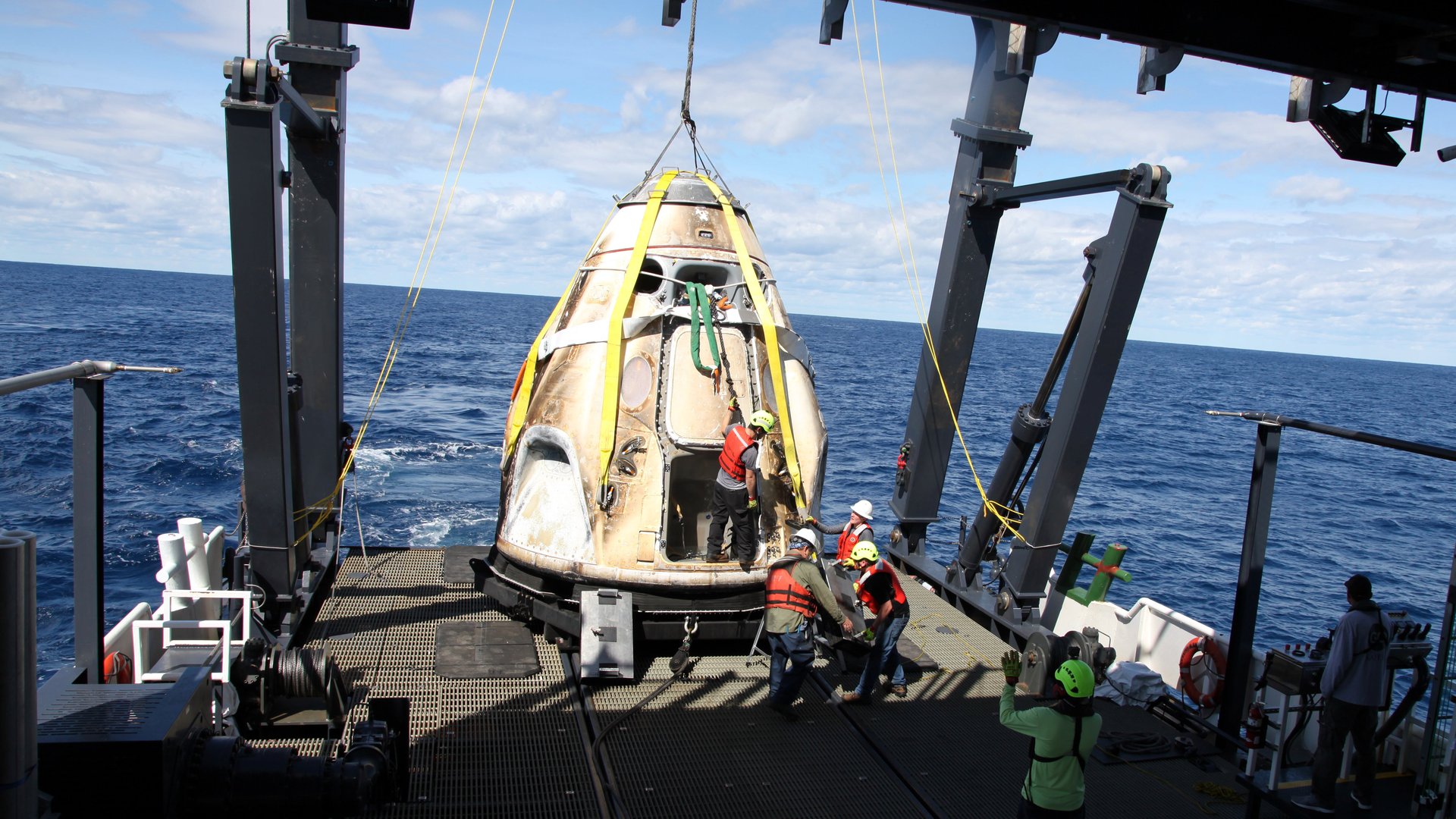

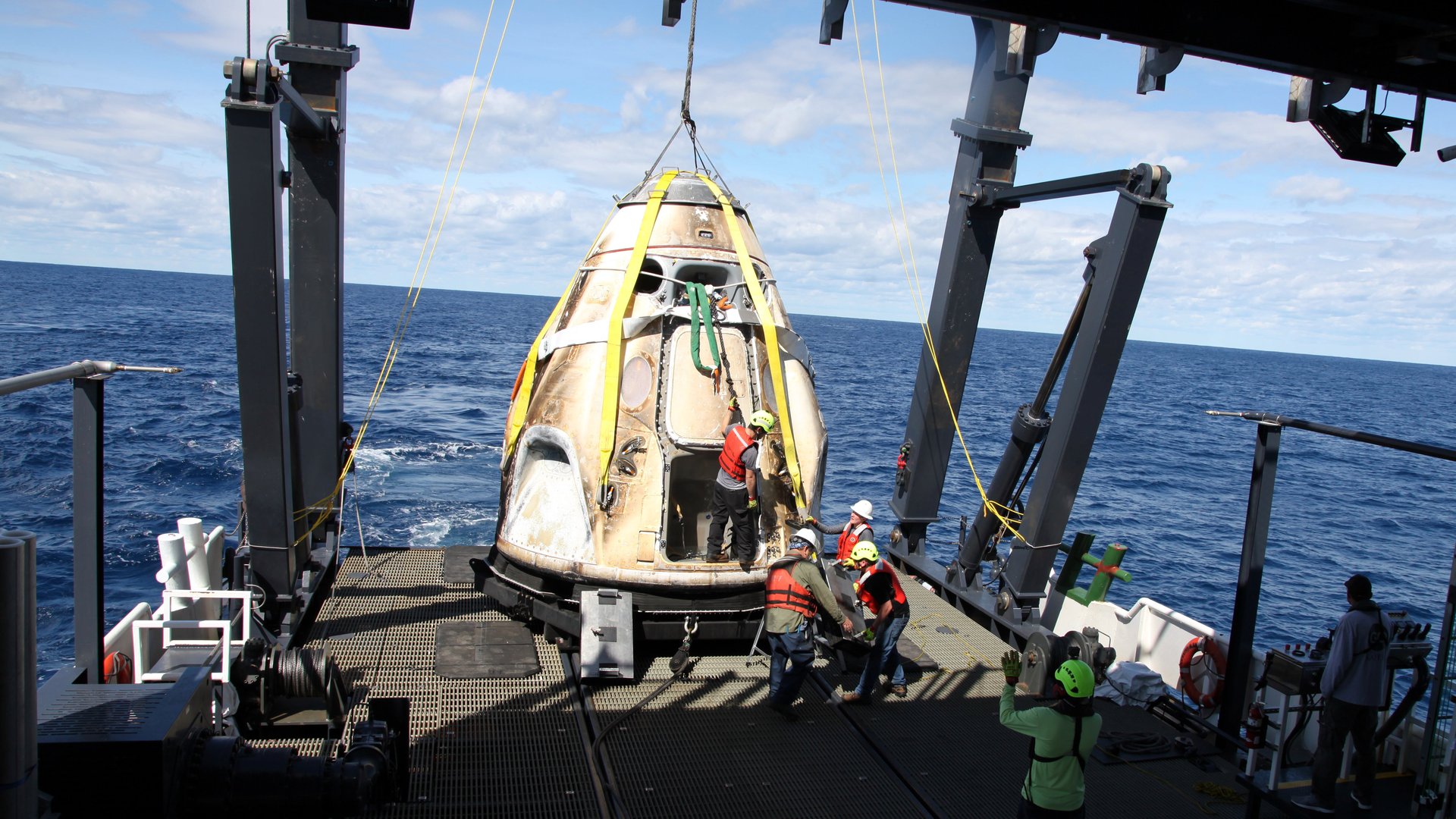

The same Dragon spacecraft destroyed in the April 20 test had been used in a successful test flight in March, when it was launched from Cape Canaveral, flew to the space station with a small cargo before returning to splash down in the Atlantic Ocean. It’s not clear how the destruction of the vehicle will affect the test schedule, though SpaceX had at least three Dragons under construction when reporters visited its Los Angeles headquarters in June 2018.

SpaceX appeared to have taken the lead in the informal race with Boeing to be the first of private contractor to fly astronauts to the International Space Station. Now, Boeing may have a chance to catch up, with an uncrewed test flight of its own scheduled for August 2019 and hopes of taking people into space before the end of the year.

NASA chief Jim Bridenstine has been a proponent of commercial partnerships as a way to do more with the agency’s budget. His ambitious plans to get astronauts back to the moon by 2024 depend in part on the success of the commercial crew program, both to free up funding and certify such partnerships as a viable path to get humans beyond Earth orbit.