Are the UK’s two leading political parties on the edge of collapse?

Though the sides may change with each election, the basic shape of British politics has remained the same for the past 200 or so years. Two parties have sat two sword-lengths apart in parliament, with a scattering of fairly insignificant minor parties on the sidelines.

Though the sides may change with each election, the basic shape of British politics has remained the same for the past 200 or so years. Two parties have sat two sword-lengths apart in parliament, with a scattering of fairly insignificant minor parties on the sidelines.

But for the first time in modern British history, this two-party structure is in doubt, with each at risk of dissolution. If either does, a system built around two parties may descend into the chaos of small parties and coalitions, with even more dithering, in-fighting, and indecisiveness than is already characterizing British politics. Brexit is the culprit.

The results from last week’s local elections lay this out in stark relief. Support for the minor Liberal Democrat and Green parties has surged, as the Labour and Conservative party saw their worst results in years. Labour, which was expecting significant gains, instead lost 82 council seats, while the Tories lost 1,334. PM Theresa May is now under pressure to resign.

“I think it is fair to say that this is the return of at least three-party politics,” political scientist John Curtice told the BBC. “But I suspect that on 23 May”—or the date of the forthcoming European Parliament elections—”we will discover that there are more than three significant players. We may see the most fragmented British electorate since the advent of mass British democracy.”

A Conservative party in tatters

Since 2016, the year the UK voted to leave the European Union, more than 20 MPs have resigned from roles in prime minister Theresa May’s government over her handling of Brexit. Some of these ministers were literally tasked with its execution, but have found developing a plan that works for everyone, or even has majority appeal, an insurmountable hurdle. May’s repeated attempts to pass her own deal with the EU have been utterly unsuccessful. Now, with less than six months to go before the UK’s new leave date, the future of the party, and its leadership, is far from certain.

Support for Brexit does not necessarily draw down party lines, though members of the public who want to leave the EU often vote Conservative. Among Tory politicians, however, a coterie of hardline Brexiteers sits uneasily alongside best-for-business-best-for-Britain Remainers, who point to the uncertainty of leaving the EU and its effect on investment in the UK. Both are increasingly unwilling to compromise on anything other than each of their ideals—a clean break, or no Brexit at all.

Jo Johnson, a Conservative MP and the brother of Brexiteer extraordinaire Boris Johnson, resigned from government in November over May’s Brexit plan. The former transport minister, who supported the UK remaining in the EU, now finds the prospect of a Conservative party split alarmingly possible. Speaking on a recent panel at the Milken Institute conference in Los Angeles, he explained the central point of contention: “Do we want to stay aligned to the EU rules and regulations that give us full unfettered access to our biggest market, or do we want to choose a different mode of regulation that gives us complete control over our laws and our own affairs, that enables us to do deals with other countries around the world including the US?”

Johnson believes Brexit is a bad economic choice for the country, but has accepted the outcome of the 2016 referendum. Now, he says, it’s time for a decision from his party—though each will come with the risk of a schism. Where some pro-Brexit MPs favored “a Singapore-on-Thames model, whereby we could be a low-tax low-regulation economy competing on the edge of continental Europe able to buccaneer around the world,” he feared others in the party would not tolerate it, and might then opt to leave altogether.

Alternatives on the up

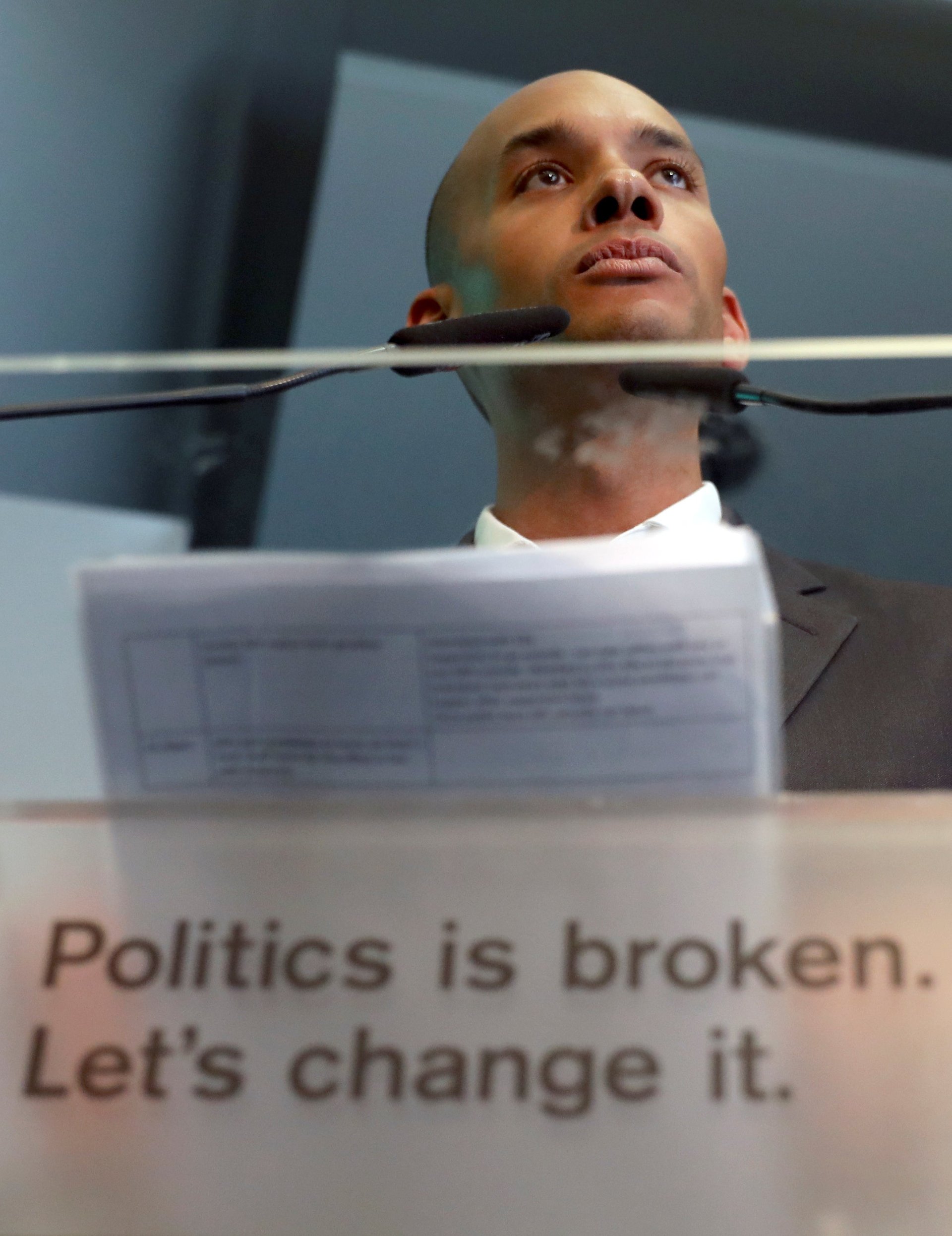

A “no-deal” outcome, or something resembling it, may thus send the Conservative party’s pro-EU MPs scurrying to other alternatives. One option is the snappily titled “Change UK—The Independent Group,” founded in April by a coalition of 11 centrist MPs from either side of the political aisle, brought together by a hatred of Brexit and a purported love of the middle ground.

So far, Change UK’s first steps of independence, which have included a series of racism scandals and no clear leadership, have been wobbly. But as the Brexit debate traipses aimlessly on, a party offering consensus may look more and more appealing. The Liberal Democrats, for instance, have consistently spoken in favor of a second referendum, perhaps contributing to their win last week of 1,350 council seats, a net gain of more than 700 since previous elections in 2015 (despite these gains, they still trail Conservative Party seats by a significant margin).

For the Conservatives, appeasing Remainers by maintaining Britain’s ties with Europe has its own risks. There is an “equally large and very vocal group of MPs on the right of the party,” Jo Johnson said, whose vision of Brexit was about “sailing the wide open seas, and reconnecting with countries around the world.” These MPs could be seduced by the Brexit Party, whose sudden explosive growth will almost certainly splinter some of the Tory voter share.

The Brexit Party, led by Brexit architect Nigel Farage, was too recently formed to take part in local elections. But it is currently besting all other British parties in polls for the forthcoming European Parliament elections, which the UK has been forced to take part in because of a failure to deliver Brexit. European Parliament elections have traditionally had very low turnout among UK voters: if current polls are accurate, a plurality of votes placed out of the UK on how the EU should be run will be in protest of the very establishment.

The Brexit Party’s only policy is that Britain should leave the European Union, and that it should do so at once, without a withdrawal agreement. Since the party’s registration with electoral authorities in February, polling has gone from zilch to 17%. At the same time, Conservative party support has dwindled, leaving the party conclusively trailing Labour for the first time all year.

Farage hasn’t attracted any MPs to leave their parties yet. Voter creep, if it continues, could see them at least considering a change of affiliation. Since May took the leadership, big-ticket donors such as the entrepreneur Howard Shore have stopped financially supporting the party. Speaking alongside Johnson on the panel, Shore said: “In my heart, I’m still a Conservative and want the party to prosper. It’s been around 200 years.” Still, he added, without a change of leadership or more direction on Brexit, the Conservative party should expect Leave voters to run for the warm embrace of the Brexit Party or simply opt out of voting altogether.

The Brexit Party’s likely success in these elections won’t change EU policy. But it might “take some of the wind out of the sails of the campaign for a second referendum, and perhaps make a still-more-Brexity turn more enticing for the Conservatives,” European political research analyst Constantine Fraser, from TS Lombard, says. This could mean the party electing a leader like Boris Johnson, who would push back on demands from Brussels. “At the same time, the more moderate voices in the Conservative party will see this as a reason to get Brexit out of the way as soon as possible—even if that means compromising with Labour. In a sense, the Brexit Party tugs the different wings of the Conservatives in different directions.”

Labour’s own travails

A splintered Conservative Party is ultimately good news for Labour—providing it can come up with a coherent party line.

The party’s own Brexit troubles have split MPs and voters. Jeremy Corbyn, its polarizing leader, seems to have adopted a policy of “constructive” ambiguity in attempt to appease both pro- and anti-Brexit factions, ultimately succeeding in pleasing neither.

His present stance is in support of a second referendum, but only under very specific circumstances: if there is no general election, and the party cannot push changes through to May’s deal. Both sides have interpreted this decision as a win. Pro-Brexit MP Gloria de Pielo reiterated that it was only “an option,” while Remainers in the party touted it as a chance for a “final say.”

But the party’s inconsistent messaging saw it punished at the polls in recent local elections. At present, Labour is pushing for a snap general election. If it wins, its job will be just as hard as the incumbent’s. With Brexiteers across the political spectrum, any deal requires bipartisan support to have a hope of being passed—including a no-deal Brexit. At present, there is no incentive for Corbyn to “sign off” on May’s Brexit. Any pro-Brexit Tory leader is just as unlikely to be prepared to compromise with Labour.

More than that, Corbyn’s own spectacular unpopularity within his party continues to make it hard to reach consensus. Well over a dozen MPs have left the party under his leadership, with some suspended for their role in the party’s ongoing anti-semitism crisis (paywall) and others quitting over their leader’s handling of said crisis.

What happens now?

Keeping the two parties intact will require strong leadership on either side. For the Tories, decisive factors might include future leadership and where it falls on Brexit. For Labour, assuming its leader remains in place, it may be a question of Corbyn finally committing to one approach on Brexit—and then working out how to bring his party together to birth a compromise that no one so far seems prepared to embrace. The collapse of either has the potential to help the other.

But none of this is easy. In the meantime, the clock is ticking, and the new leave date of October 31 approaches. The policy of pushing decision-making further and further down the line cannot continue forever, while markets remain in turmoil until some kind of line is drawn. With its two biggest parties stuck in the mud, Britain’s voters are beginning to lose patience. The message from voters, Labour shadow chancellor John McDonnell said, is: “Brexit—sort it.” But guidance on how is no more forthcoming than ever.