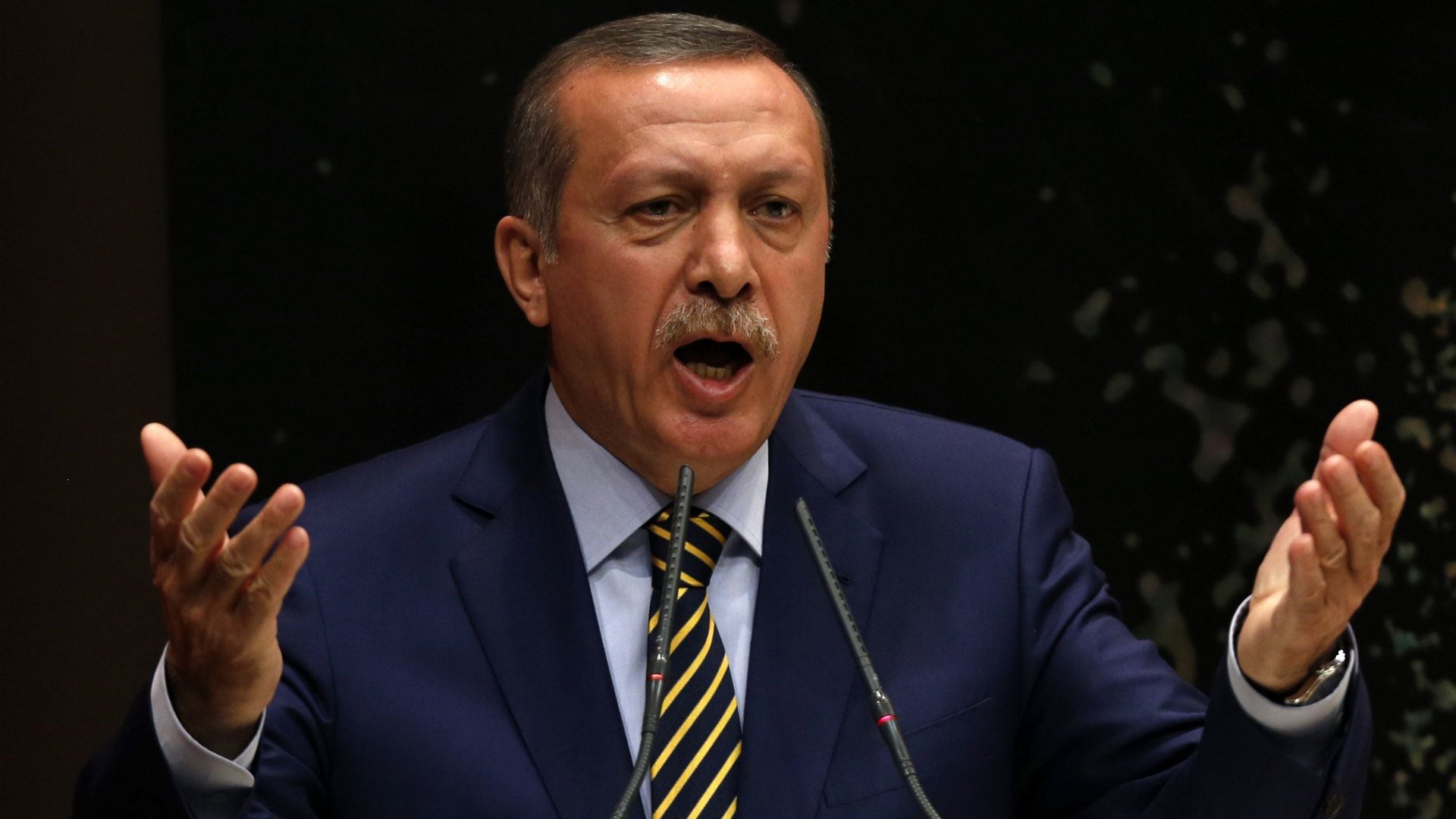

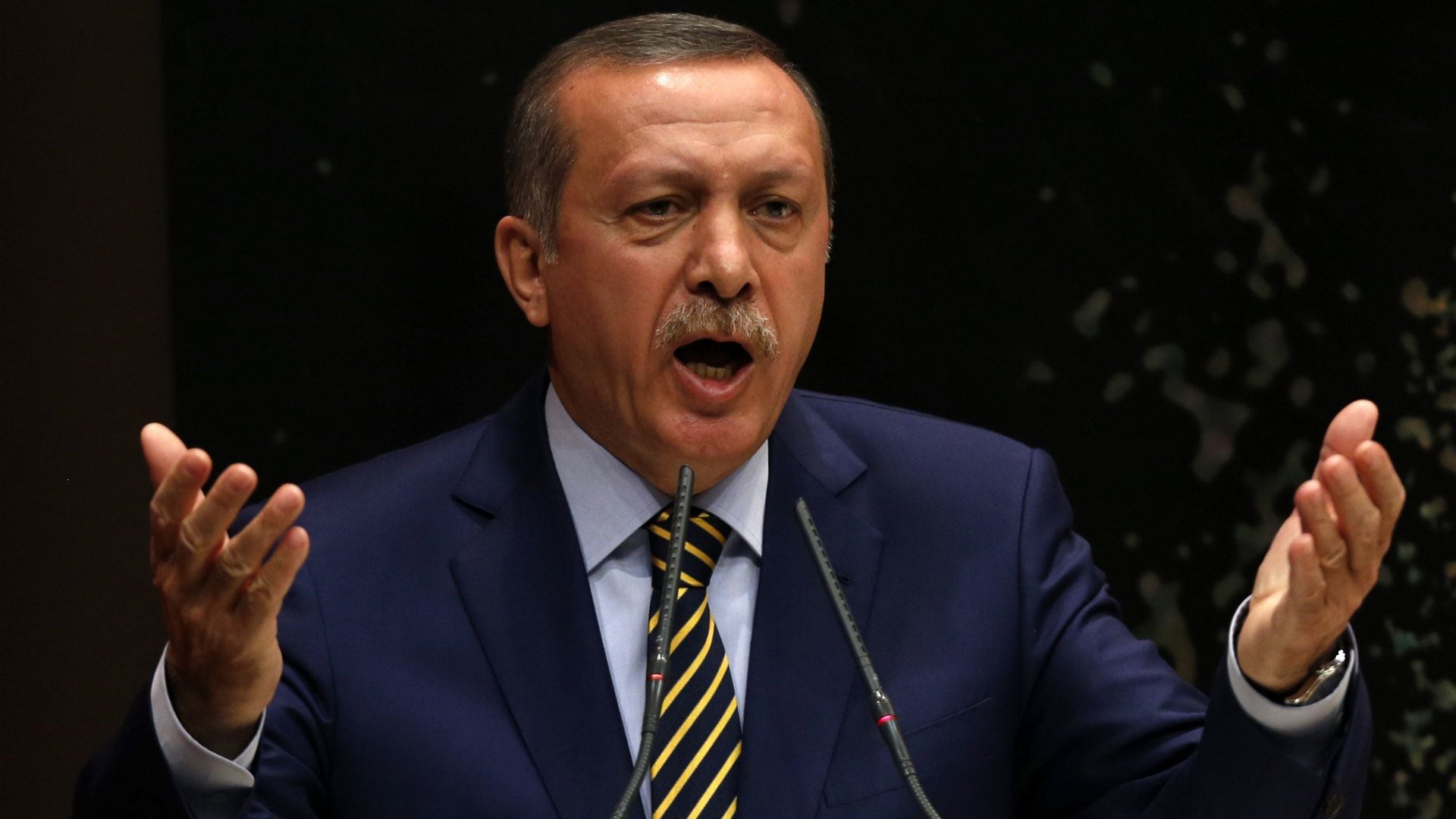

Shoeboxes of cash, Iranian gold, and the other allegations threatening to bring down Turkey’s government

Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan is under increasing pressure due to an ongoing corruption and money laundering scandal. Yesterday, in the latest twist, three of Erdogan’s top officials—the Ministers of the Economy, Interior, and Environment and Urban Planning—resigned after their sons were implicated. Erdogan responded by reshuffling his Cabinet. The details at the center of the turmoil, which began on December 17 with a corruption investigation and has since snared 24 people, make for colorful reading:

Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan is under increasing pressure due to an ongoing corruption and money laundering scandal. Yesterday, in the latest twist, three of Erdogan’s top officials—the Ministers of the Economy, Interior, and Environment and Urban Planning—resigned after their sons were implicated. Erdogan responded by reshuffling his Cabinet. The details at the center of the turmoil, which began on December 17 with a corruption investigation and has since snared 24 people, make for colorful reading:

Shoeboxes full of cash

Police reportedly confiscated $4.5 million found inside shoeboxes—there was no word on how many—on bookshelves at the home of the chief executive of the state-run lender, Halkbank. The CEO’s wife said in a wiretapped conversation, in reference to the money, that “the greens have arrived,” according to Turkish news agency Dogan. But the funds were for the construction of Islamic schools in Turkey and Macedonia, the CEO told Turkish newspaper Hurriyet. Meanwhile, authorities reportedly found more than $1 million in cash at the home of the Interior Minister’s son. The minister said the money was from the sale of a high-end villa.

Construction bribes

One assertion is that officials took bribes to approve construction projects despite zoning rules. The Environment and Urban Planning minister, who said he only quit under pressure, has defended his actions. He said Erdogan himself approved a ”great proportion” of projects supposedly in question, and said the prime minister should step down. Indeed, construction projects are a touchy subject: Massive anti-government protests last summer began in response to a plan to develop a popular Istanbul park.

Money transfers to Iran

Turkey has had a complex business relationship with Iran, as Reuters explains, with gold playing an important role:

Turkey has bought natural gas and oil from Iran through an indirect system whereby Iranian exporters received payment in Halkbank lira accounts and used that money to buy gold. The bulk of that gold was then been shipped from Turkey to Dubai, where Iran could import it or sell it for foreign currency.

Details are unclear, but part of the corruption allegations seem to involve illegal money transfers to Iran. Halkbank, however, says all of its operations have been above board. Ultimately, analysts say the corruption investigation is driven by a power struggle between Erdogan and Fethullah Gulen, a moderate Muslim cleric who left Turkey in 1999 and is now based in Pennsylvania.

Erdogan has been in power for 11 years, and the scandal—which he says is a foreign plot against him— is his biggest test yet. And there may be more to come, too. “Forced to act, Erdogan tried to get rid of his burdens,” said Atilla Yesilada, a risk consultancy analyst, of Erdogan’s ministerial firings. “But this is a political crisis, and it is hard to tell how it will unfold, these investigations may expand in coming months,” he told The Wall Street Journal.