The web is a disaster—but the person who created it still has hope

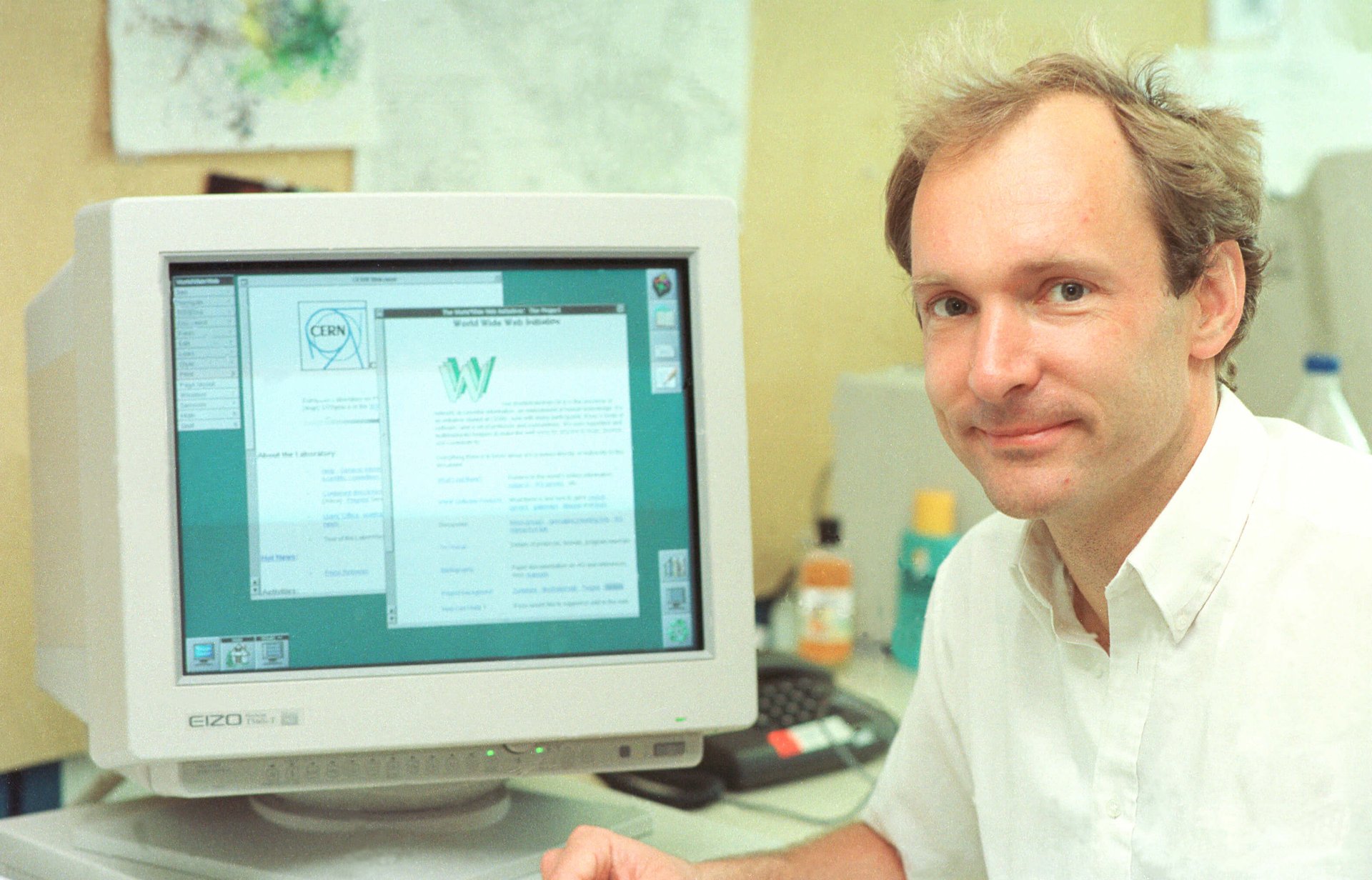

In 1989, Tim Berners-Lee was working as a fellow at CERN, the science research facility in Switzerland. He feared that the information people needed to solve some of the world’s most pressing problems would be siloed on researchers’ computers—blocky devices that only recently had been built small enough to fit on a desk.

In 1989, Tim Berners-Lee was working as a fellow at CERN, the science research facility in Switzerland. He feared that the information people needed to solve some of the world’s most pressing problems would be siloed on researchers’ computers—blocky devices that only recently had been built small enough to fit on a desk.

His solution: creating the World Wide Web as a decentralized way for people to share information digitally.

In March, the web turned 30. We thought it was a good time to check in with Berners-Lee about whether the web as we know it has lived up to his vision, what has surprised him about its development, and how the web will be better for everyone in the future.

This conversation has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

Quartz: In the past, you’ve noted that you conceived of the web as “a common information space in which we communicate by sharing information.” Has it achieved that?

Tim Berners-Lee: Yes and no. The original idea came when I was working at CERN—the web was one of the software projects I had. Most of the input on these software projects would be from physicists or students—people who were passing through and could lend a summer or six months to helping code a project.

I wanted it to be this space where anybody working on the project had this bit of the web where they could easily add in an idea. When they had meetings, or when they made decisions, they leave a trail of breadcrumbs for how they came to that decision.

The web should be able to link anything to anything. Any idea that you had would go quickly to the web, and any idea the web had in it would move quickly to you. The vision was that the team would be in equilibrium. We’d have a very good level of sharing of information, including half-formed ideas. It wasn’t supposed to just show what we know, but also what our problems are, and how they connect. What if I have a problem and the two pieces of the solution are in different people’s heads? That was the sort of thing I was going for.

Collaborative systems like Github are a good environment for developing things like software. It’s amazing how you can Github with people while other people will join the project and help you with it. It is quite nice, but it doesn’t pay off as if we really achieved that full vision of the web.

And of course, along the way far more people started using the web. There was a feeling that because there was more communication, then surely there should be less miscommunication, and more mutual understanding. And in that case, there should be less conflict. There should be global peace and harmony.

During the first seven to 10 years, people were making blogs. Those blogs were achieving heights of wonderfulness—they were linking to each other’s blogs, and the blogosphere in general seemed to be a wonderful, collaborative work that was of ever and ever rising quality.

Then Wikipedia came along and captured that spirit of working together toward ever and ever higher quality. Then I think that there was a hope that the web could possibly support not only great processes for finding out what to believe, but also for figuring out finance and knowledge, processes for what to decide to do—basically, political processes.

We found out that Wikipedia arrives as a pretty good repository for scientific fact, but we didn’t get the equivalent of the United Nations arriving as a pretty darn good way of settling any political multinational issue.

But who knows. There’s no reason why we shouldn’t—why somebody shouldn’t—think of how to do that in the next few years.

You note that you wanted the web to become “a realistic mirror (or in fact the primary embodiment) of the ways in which we work and play and socialize.” Did you anticipate that online behavior could, in fact, change how we interact in the real world?

Well, to a certain extent we did. At the web science conferences, we’ve said all along that it’s really important to look for things like unintended consequences.

What happens if, on the web, a cultural revolution happens overnight on Twitter while you’re asleep, and you wake up and find that a destructive meme has spread across the internet, and all your normal sources of authority that you trusted when you went to sleep are now distrusted by most people? That sort of model of what could go wrong, we thought, was quite motivating.

Since then, people have looked at how different emotions propagate across the internet, across social networking systems, and so on. And there are people who have looked at the way this has been abused, like in the case of the Martha Coakley election. I don’t know if you remember, but she was Twitter-bombed—it was a deliberate attempt, a deliberate plot, to use the internet to very effectively shoot her down.

And people who analyzed that have come back and said, yes, the Facebook hacking in the last election was the same technique, in fact.

Did we ever imagine this? People who did web sciences, they did. They have a told-you-so card they can play at this point, now that they’ve seen massive election fraud.

What about the web today has surprised you? What has turned out better than you predicted? What has been a more negative surprise?

I had this sort of utopian dream that good knowledge would become ubiquitous. So I suppose what surprised a lot of us was when we realized that, for all the groups of people nurturing their bookmarks to Wikipedia and helping to make it better, there were equal numbers of people, something like 48% of the world, that actually believed all kinds of conspiracy theories.

That’s partly because people love a good conspiracy theory, and partly because there are people who don’t know they have been manipulated very deliberately into believing those things because it’s in somebody else’s interest. I think a lot of people were shocked to find out the state of misinformation out there, because they learned to manage their bookmarks and very carefully select the things that they read. Not everybody is in the same sort of bubble. That was a shock.

Was there a catalyst for that realization to happen? Was there a year? Or did it happen little by little?

When you’re talking about the impact on the attitude of the person in the street, Cambridge Analytica was a bit unique. It wasn’t about how you were being manipulated to buy something. It’s about how all the information you’ve carefully typed into these platforms is being used to manipulate other people.

It was this fusion of a benevolent system that people had enabled by their own membership of social networks who suddenly realized that their participation in the social networks was actually part of a much more sinister process, which was actually a political effect rather than just a commercial gain.

How about a positive surprise?

From the beginning, the day the first people started sending me emails about helping on the web project, it was amazing. The spirit of collaboration. In 1993, Kevin Hughes sent me a note about the Honolulu Community College dinosaur exhibit. He scanned in some photos of some postcards of dinosaurs. People would email me about that.

When the Vatican had this amazing exhibit of renaissance art and they took it to the Library of Congress and the Library of Congress scanned it, people would make a website and email me and say, “Look!” Suddenly I had this mind-boggling access to medieval manuscripts on my screen. There have been a lot of times when I have been blown away by the positives, over the years, certainly.

That dinosaur exhibit, was that one of the first emails you received of that kind?

I kept a list of all the websites that I knew about—there were 26. It may have been one of the first 26 [Editor’s note: this site does not appear on that list]. But then, of course, the point about the web is that it’s decentralized. There’s nobody who knows how many websites there are, because you don’t have to ask anyone’s permission to make one.

What do you think the web will be like in another 30 years?

In another 30 years, if all goes well, you will look back and you will tell your kids, “When we celebrated the 30th anniversary of the web, Wikipedia was nice, there were some things that were pretty nice, but a lot of stuff, like the political discourse, was really horrible.”

You’ll say, “You will never understand, because now, the political discourse is so effective. Now, because of some of these websites that people introduced in the 2020s and 2030s with very, very carefully curated processes for allowing respectful, responsible, open, accountable public discourse between people of different political persuasions, between people of different cultures and of different languages.”

You’ll say, “Believe it or not, when you were born, we didn’t have that. Politics was a real mess. Don’t go there, it was horrible.”

So, in the future, hopefully not only will we have great processes for arriving at what to believe, but also great processes for deciding what to do. And maybe we’ll have much more understanding between people of different countries. That’s what we need to aim for.

This web is anthropogenic. It’s difficult enough convincing people that climate change is something caused by humans—the web is definitely caused by humans.

If you hear people saying, “Oh but the companies are so big! There’s so many people who have accounts on the social networks!” Well, yeah, lots of people have accounts on there.

When we built the web, AOL was cool, but then it just wasn’t as interesting anymore. Then people were worried about Netscape being dominant. Netscape had complete control of the web. It was the only web browser.

There’s always been cases where it seemed everybody has been using the same browser, the same phone company, the same oil supplier. But in fact, we can change it. We can always make another. There’s always somebody designing a new system, with an even better idea that will make the world an even better place.

We’re at another inflection point now, right? Can you tell me about it?

The 50% point is now. Right now, if you believe the ITU figures, 50% of humanity is online in some version. They can use the web. They have a data connection to the internet and something like a phone they can use with it. We would be celebrating that, if we weren’t celebrating the 30th anniversary.

The fact that these two milestones come together really means it’s a time to take stock. There are lots of questions about how we can most rapidly get the other half online as quickly as possible, which is a lot about affordability, about keeping the cost of your first data connection down. For example, suggesting people should get 1 Gigabyte for 2% of a monthly income. Things like satellites will become important for reaching those people for whom it’s too expensive to get fiber to them, for example.

Accessibility for people with disabilities has always been a strong point of the web. It has more accessibility than most things, like books.

There are also interesting questions looking forward: When that 50% online becomes 80% online, are there completely different issues coming to the fore? Are the other 20% becoming more and more disenfranchised? For most governments and companies, why should they bother looking after the 20% who can’t even be bothered to get online, or go online and they can’t read? They won’t make anything available to them if we’re not vigilant.

But as the reasons for people not being online become more varied, then the techniques we have for tackling them will become more varied as well.

Editor’s note: A previous headline on this story incorrectly described Berners-Lee as inventing the internet. It has been updated to reflect his role as inventor of the internet-based World Wide Web.