Why big-box and mom-and-pop shops both matter in emerging markets

Multinational manufacturers looking to hawk their wares in booming emerging markets shouldn’t write off mom-and-pop shops just yet. Just because an urbanizing middle class shops at mushrooming big-box stores like Wal-Mart and Tesco does not mean that old-school kiosks and neighborhood groceries are disappearing. ”Eventually, mom-and-pop stores may go the way of buggy whips,” McKinsey director Alejandro Diaz wrote with colleagues Max Magni and Felix Poh in McKinsey Quarterly this month (registration required). “For now, though, manufacturers staking their futures on these booming economies must forge lasting relationships with a diverse set of retailers—before competitors do.”

Multinational manufacturers looking to hawk their wares in booming emerging markets shouldn’t write off mom-and-pop shops just yet. Just because an urbanizing middle class shops at mushrooming big-box stores like Wal-Mart and Tesco does not mean that old-school kiosks and neighborhood groceries are disappearing. ”Eventually, mom-and-pop stores may go the way of buggy whips,” McKinsey director Alejandro Diaz wrote with colleagues Max Magni and Felix Poh in McKinsey Quarterly this month (registration required). “For now, though, manufacturers staking their futures on these booming economies must forge lasting relationships with a diverse set of retailers—before competitors do.”

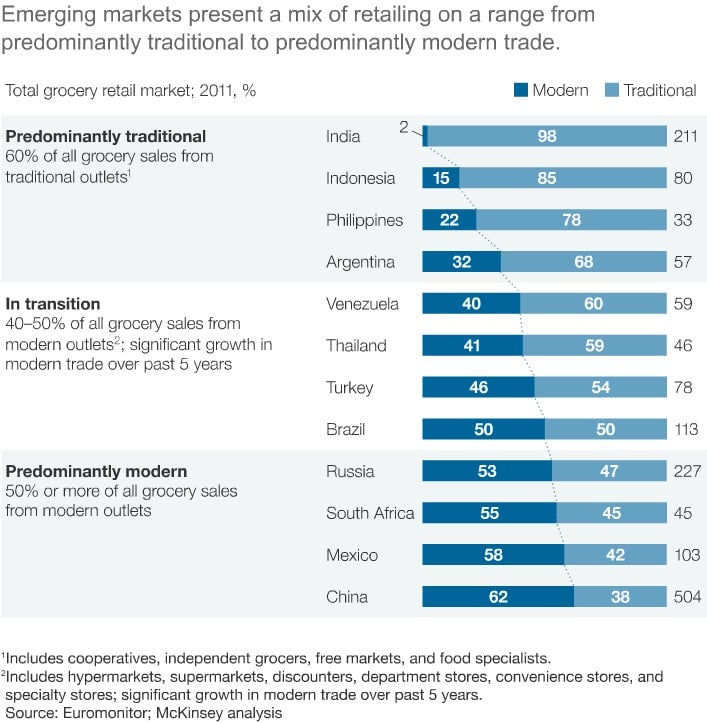

As this chart shows, McKinsey groups emerging consumer markets into three kinds: “traditional markets,” where small shops predominate (India, Indonesia, Nigeria); “transitional markets,” which are quickly changing (Brazil, Turkey, Thailand); and “modern markets,” where more than half of groceries are already sold at big chain stores (China, Mexico, South Africa).

There’s still a big gap between these “modern markets” and Western countries, though. In the US, the 10 biggest grocers account for 51% of sales; in China, the top 10 comprise 11%, according to McKinsey.

The consulting firm makes four recommendations to multinationals wanting to tap consumers in all three types of markets:

1. “Embrace the duality.” Target both traditional and modern retail—whether starting small and then going big, or starting big and then spidering out to small shops. Both models have pros and cons: modern outlets offer refrigeration, shipping and marketing; but they’re so big, they can force suppliers to give them discounts. Small stores, in contrast, can be costly to reach, but can net a higher return.

2. “Segment and conquer.” Consumer-product companies should build brands city by city—not just tailoring products to customers, but tailoring incentives to retailers. Big stores may care most about product discounts; small ones may prefer things like free equipment or advertising, or even savings on health insurance or electricity.

3. Distribution: “Balance cost and control.” Manufacturers should deliver directly whenever possible, but shouldn’t shy away from hiring other distributors to reach remote areas, too. But they should also be just as careful choosing distribution partners as they are in choosing retail outlets.

4. “Skills and technology.” Manufacturers should train their own sales force, providing standardized metrics and performance checklists and using mobile technology to track performance.

Uneven income distribution and development across emerging economies only make these kinds of two-track strategies more important.