Why $200 million won’t make Crocs popular again

Shares in rubber clogs maker Crocs have been soaring today after the company secured a $200 million capital injection from the private equity firm Blackstone and fired its CEO. But the funds won’t do anything to solve one problem facing the company: Its products are no longer popular.

Shares in rubber clogs maker Crocs have been soaring today after the company secured a $200 million capital injection from the private equity firm Blackstone and fired its CEO. But the funds won’t do anything to solve one problem facing the company: Its products are no longer popular.

Colorado-based Crocs started selling its distinctive, colorful rubber clogs in 2004, and they quickly became an overnight sensation, popular among backpackers, chefs and other people spending most of the day on their feet.

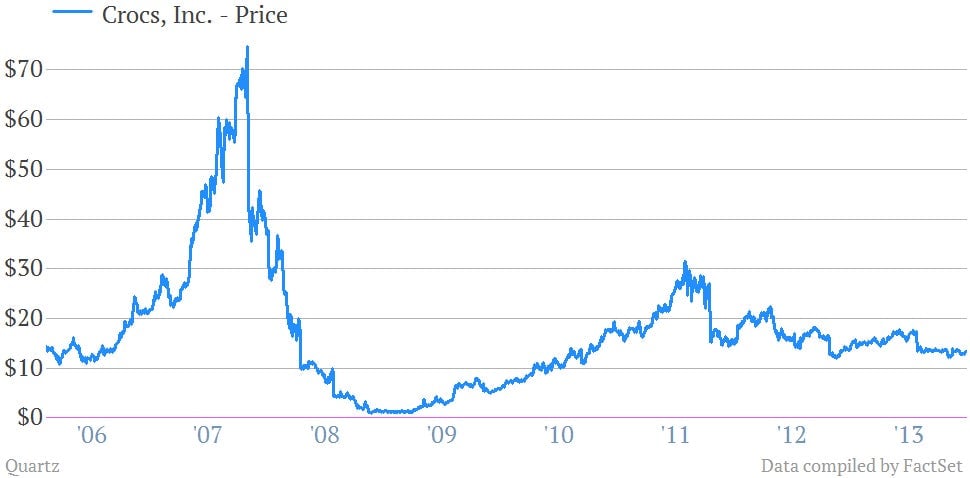

After going public in 2006, Crocs’ share price increased by more than 600% in a little more than a year. But the company was soon hit by what John McCarver, the CEO ousted today, described to CNN as a “perfect confluence of events.” A fierce backlash on social media against its by then near-ubiquitous clogs, combined with aggressive competition from cheap knock-offs and the great recession, sent Crocs sales, profits and its share price into freefall.

McCarver, who took the CEO reins in 2010, responded by expanding the company’s product set, launching rubbery versions of sneakers, docksiders and ballet flats, for example. As the diagram below from the company’s website shows, it now makes more than 300 different styles.

McCarver also increased the company’s reach: In the face of waning sales, it opened nearly 100 new outlets in the year to September 30. The results, however, have been mixed. While sales growth chugged along, profit has fallen precipitously, with deep double-digit declines in the three of the past four quarters.

After a highly critical analyst report questioned McCarver’s leadership earlier this year, Crocs put itself up for sale. There was little interest from trade buyers: The company makes its footwear using its own proprietary “soft, comfortable, lightweight, non-marking and odor-resistant” technology, which other shoe-makers couldn’t easily use for their own products.

Which brings us the company’s latest turnaround plan. The new CEO will be charged with improving earnings, more than growing sales, and is likely to stop opening new stores. This sounds reasonable enough, given that the recent expansion frenzy has yielded negligible returns. But the funds from Blackstone’s $200 million investment won’t be used to develop new products, for marketing, or to improve its brand. Rather, they will be used to buy back company stock (which in theory, should put a floor under the share price).

It’s a common dictum in business that you can’t cut your way to growth. Financially engineering it is surely no easier. The share buyback might boost short-term shareholder returns, but it certainly won’t do anything to improve the Crocs brand in the eyes of consumers.