China’s reform plans could put a big dent in Macau’s $45 bln casino business

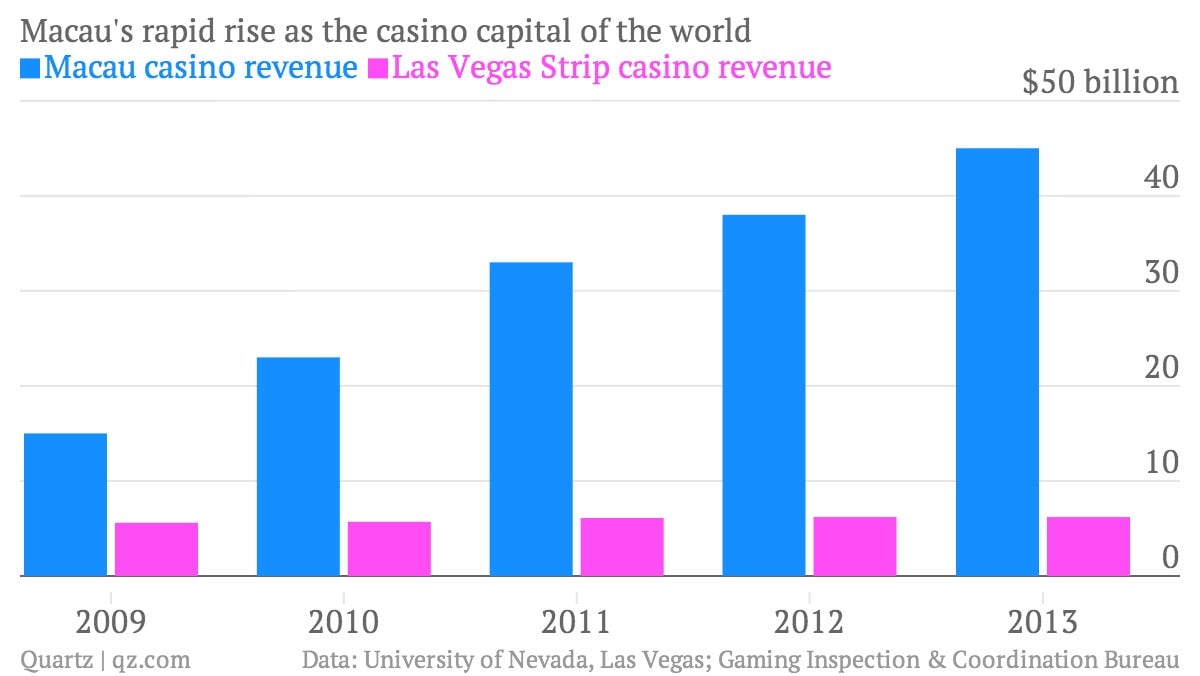

Macau’s casino business—which includes hedge fund faves Las Vegas Sands and Wynn Resorts—continued to trounce the competition in 2013, pulling in 361 billion Macau patacas, or $45 billion, up almost 19% on 2012. The Las Vegas Strip, by comparison, is on track to bring in less than 15% of that total—just over $6 billion.

Macau’s casino business—which includes hedge fund faves Las Vegas Sands and Wynn Resorts—continued to trounce the competition in 2013, pulling in 361 billion Macau patacas, or $45 billion, up almost 19% on 2012. The Las Vegas Strip, by comparison, is on track to bring in less than 15% of that total—just over $6 billion.

Macau’s growth sure seems unstoppable. But there’s one threat that looms ever larger: the Chinese government’s plan for reform.

As president Xi Jinping announced in November, the government is pushing forward with reforms that will see it gradually liberalize interest rates and open its capital account. Macau casino operators have existing capital controls to thank for unknown but undoubtedly huge portions of their revenue.

Chinese citizens aren’t allowed to move more than $50,000 a year out of the country. One of the only ways of circumventing these controls is through Macau’s shady triangle of VIP baccarat rooms, “junkets” and underground banks. ”No funds actually cross the border, so this method is difficult to detect and impossible to measure,” Stephen Green of Standard Chartered told the Wall Street Journal (paywall) in 2012.

To quote from our Oct. 2012 article, here’s how it works:

1) Sign up with travel companies known as “junket operators.” These high end tour agents make a living transporting Chinese gamblers to Macau and arranging their accommodation and, crucially, their casino credit.

2) Borrow money from the junket operator to fund the gambling.

3) Head to casino and pick up gambling chips from the junket [usually in VIP baccarat rooms run by the junkets].

4) The chips the junkets provide are called “dead” chips because they can’t be traded for cash and have to be played. But when a player wins a bet, he is paid in cashable chips, which he can exchange for Hong Kong or US dollars inside the casino.

But as the government gradually loosens capital controls, households and businesses will be able to move capital across Chinese borders more freely—and will have less need to run money through Macau’s VIP rooms. VIP rooms accounted for more than 70% of Macau’s revenues, reported The Economist in 2011.

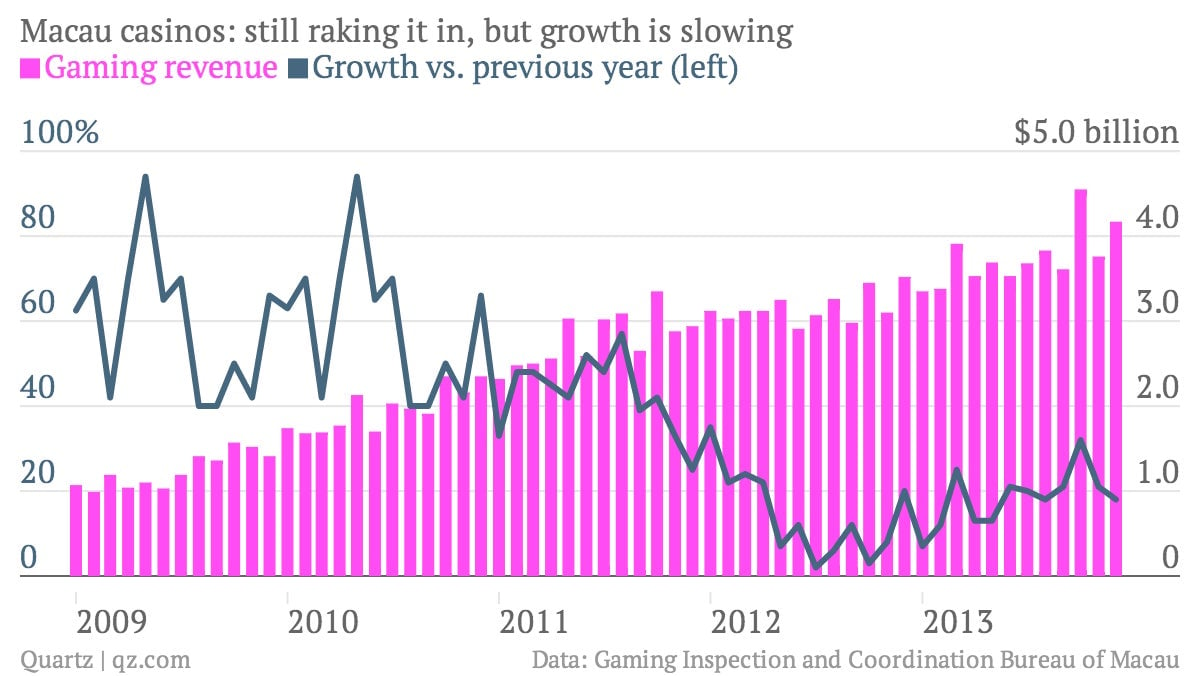

Of course, despite their lip service to the idea, Chinese leaders could well continue to sit on reforms. In the meantime, though, this chart offers another cause for concern:

Many China-watchers suspect that much of China’s trillion-dollar stimulus starting in 2009 found its way to Macau, via the accounts of state enterprise bosses. Tellingly, gaming revenue growth plummeted in 2012, when the government began tightening, picking up only after the government re-opened the spigots in 2013. Shadow banks that facilitate tens of millions a day in foreign-currency exchange via Macau also support local governments and small businesses with credit, as Reuters reported in Jul. 2013. Tighter lending conditions in 2012 aimed at reining in local government debt left them with less money to lend to Macau.

The correlation isn’t definite. But if it’s there, it means that the Chinese government’s push to impose discipline on leveraged businesses and local governments could make double-digit growth in Macau casino revenue a thing of the past.