One of the world’s weirdest birds is on the brink of extinction. Can technology save it?

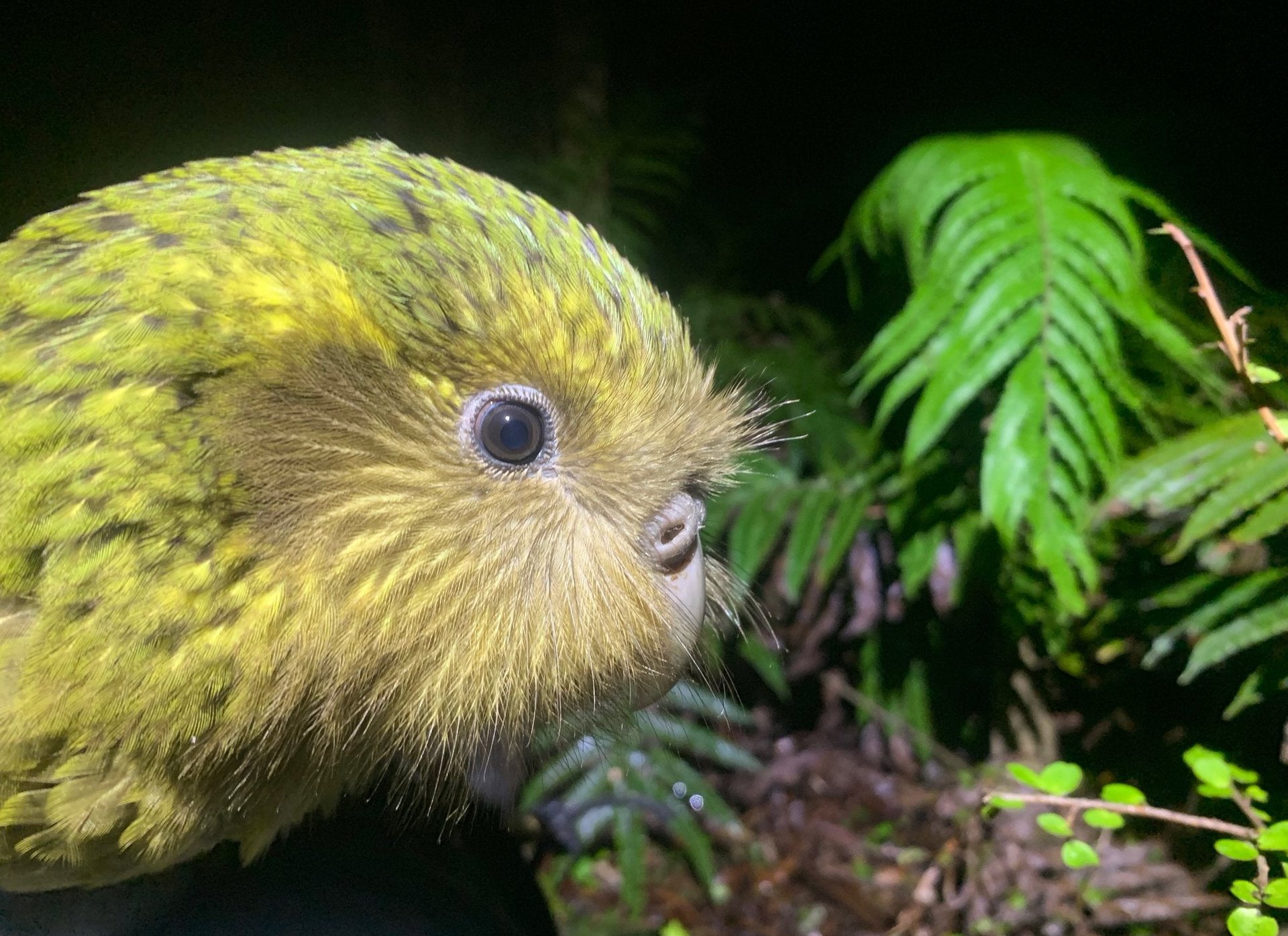

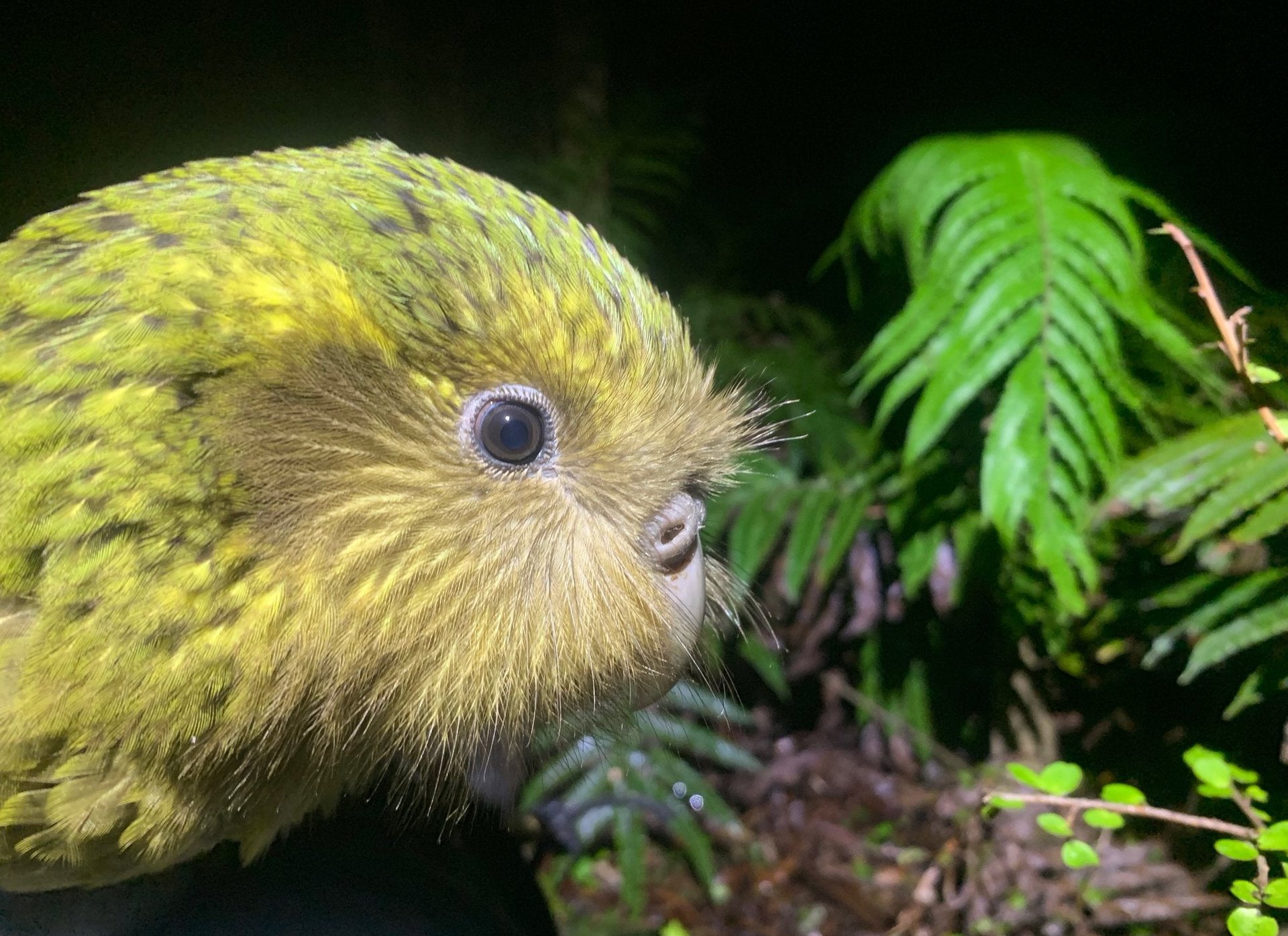

On an island off the coast of New Zealand lives a rather bizarre bird. It’s the world’s heaviest parrot (it can weigh up to five pounds), one that also happens to be nocturnal and flightless. It freezes when scared, and is the only parrot in the world to put on elaborate breeding displays. It reproduces only when it has enough food from a specific tree, which ends up being only every two to four years. It’s also incredibly charismatic and endearing—I’d bet it’s one of the only parrots to ever inspire a viral meme, one that has been described as “a mix between owl and muppet” and as having a “teddy-bear-like quality to it.”

On an island off the coast of New Zealand lives a rather bizarre bird. It’s the world’s heaviest parrot (it can weigh up to five pounds), one that also happens to be nocturnal and flightless. It freezes when scared, and is the only parrot in the world to put on elaborate breeding displays. It reproduces only when it has enough food from a specific tree, which ends up being only every two to four years. It’s also incredibly charismatic and endearing—I’d bet it’s one of the only parrots to ever inspire a viral meme, one that has been described as “a mix between owl and muppet” and as having a “teddy-bear-like quality to it.”

This bird is called the kakapo. There are only 143 adults left. It isn’t just peering into the abyss of extinction—it’s dangerously close to toppling into it.

It’s no accident that there are even that many kakapo left. In the 1980s, government-funded scientists took the dramatic step of relocating the remaining kakapo population to the small island where they currently reside, away from the small mammal predators that have decimated their numbers.

Today, scientists working to save the kakapo are using some of the most sophisticated technology in conservation today. They’re doing it in the hope of not only helping the kakapo’s numbers rebound, but to help save some of the other hundreds of bird species worldwide faced with extinction.

Each kakapo, like in many other conservation programs of birds and other animals, wears a tracker that fits on it like a backpack. This allows scientists to track their location, to feed them the appropriate amount (a sensor in the tracker opens each bird’s individualized feeding station), to assess how active they are, and to tell if they’ve mated and with which other bird (the scientists give each mating session a “quality score”).

“If they didn’t have transmitters on, they would probably be extinct now, or close to it,” says Andrew Digby, a kakapo scientist for the New Zealand department of conservation. The transmitters have made it possible to keep birds away from predators, and to manage their breeding. “Without them, there wouldn’t have been any reproduction for the past 30 years,” he says.

There’s more. Since the offspring have such a high mortality rate, the scientists incubate eggs in the lab, filling the nests instead with 3D-printed ones that make noise and move (other conservation programs have tried using dummy and artificial eggs for various purposes). This is in the hope that, when scientists return the newly hatched chicks to their nests, the mothers will feed and raise them normally. Digby says he doesn’t know yet if those efforts are successful.

Scientists also started using drones. While many other conservation projects have started to use drones, the kakapo researchers use them specifically to carry sperm across the three islands on which the kakapo live, called Whenua Hou, Maud Island, and Hauturu, all of which are uninhabited by humans (except for scientists) and predator-free. The researchers have been working for about a decade to artificially inseminate kakapo to ensure genetic diversity (in a separate project, the researchers also sequenced all the kakapo’s genetics—far from the first time scientists have sampled birds’ DNA, though it’s still rare to do for an entire population).

They’ve had limited success. Sometimes, a fertile female is on the opposite side of the island from a genetically suitable male. “With artificial insemination, time is everything. The longer the sperm is outside the male, the better chance it has of degrading,” Digby says. Drones with automatic flight paths, plus a team to attach and receive the package, save time in getting the sperm to where it needs to be.

You might think that all this effort might be warranted for a keystone species, one integral to the function of an ecosystem. But no one knows if the kakapo was ever so important. Kakapo were really common in New Zealand until about 150 years ago, Digby says, when the introduction of small mammal predators, like rats and stoats, decimated their numbers. “From an ecosystem point of view, we don’t know what [bringing the kakapo back to stable numbers] would produce. They would be amazing seed dispersers, which would be important from ecological ecosystem point of view,” Digby says.

But also, people just love them. “Kakapo are like the panda of the bird world,” he adds. “People really engage with kakapo, people who wouldn’t otherwise normally be interested in conservation or wildlife at all.”

The efforts of Digby and his team seem to be paying off. This year, the kakapo had a particularly good breeding season, resulting in 73 chicks. They won’t all survive, Digby knows (they count them as adults if they survive past 150 days, and the oldest is at about 110 at publication), but if they did, they would increase the global kakapo population by 30%.

As 1,300 species of birds worldwide also face extinction, some conservation teams are going to elaborate—and expensive—lengths to save charismatic bird species, perhaps most famously including the whooping crane and the California condor. And as our conservation needs have grown exponentially, the technology has advanced only a little. Now, other conservation teams seem interested in adopting similar techniques. Another group in Australia, working with the almost-extinct western ground parrot, and one in Indonesia expressed interest, he says, though nothing specific has come out of it yet. A team working to conserve the vulture is using similar 3D-printed smart eggs to leave in the nests as the scientists incubate the eggs.

Digby knows he’s fighting a tough battle. At the moment, the kakapo are encountering a particularly rough patch—they’re in the midst of an outbreak of aspergillosis, a fungal lung infection, which is causing their numbers to drop even further.

“If we lost the kakapo, the world would still go on. But we would lose a small and distinct piece of our ecosystem,” Digby says.

But he’s holding out hope. His goal is to get a stable population of 500 adult kakapo (generally a large enough population to ensure genetic diversity), to expand the area where they live, to incorporate imagery technology to better predict their breeding seasons. If the New Zealand government is successful in removing its small mammal predators by 2050, as it plans to do, Digby would like to reintroduce kakapo to the mainland. “If there are large areas that can be cleared [of predators], we can put kakapo back there,” Digby says.

Why work so hard to save the kakapo, you might wonder? Because it could help save everything else.

“If people can see kakapo, be interested, they’ll end up caring about where kakapo lives,” Digby says. “It’s a really good flagship species, a gateway species to get people into conservation and wildlife.”