A big reason Beijing is polluted: The average car goes 7.5 miles per hour

China simply can’t get people off the roads.

China simply can’t get people off the roads.

Especially in Beijing: Despite issuing a third-fewer new car license plates, car-obsessed residents have already figured out how to dodge the limits, as we recently detailed. It’s gotten so bad that, as the Wall Street Journal reports, Beijing’s average travel speed is only 7.5 miles per hour (12.1 kilometers per hour):

That means someone running just under an eight-minute mile could get where they’re going faster than a car in Beijing. Of course, that’s a big health gamble, given Beijing’s notorious air pollution, which is thought largely to come from smog-pumping power plants, factories and steel furnaces.

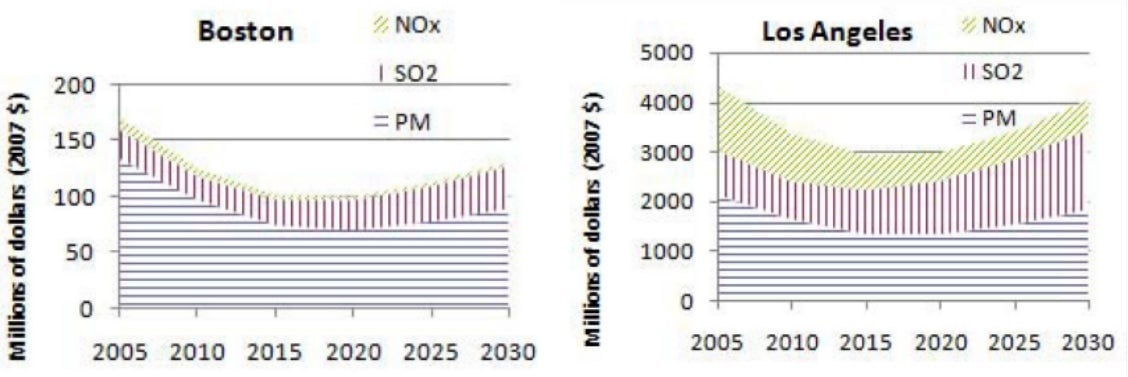

But though government research groups recently downplayed traffic’s impact on air quality, the two are certainly linked. Stop-and-start traffic means alternating between braking and accelerating. That burns more gas, spewing more toxic fumes into the air. The “golden zone” for efficient fuel use is 45-65 miles per hour. In the most extreme gridlock in major US cities, the lowest speed is 20 mph (see file) on an arterial street, and 35 mph on a freeway, according to a recent study in Environmental Health.

China’s car-produced pollution is undoubtedly expensive. The EH study found that premature death caused by traffic congestion will cost the US at least $13 billion in 2020 and $17 billion by 2030, in 2007 dollars. And that toll is clearly higher in cities like Los Angeles, where cars are de rigeur. LA incurred more than $3 billion in pollution-related mortality costs in 2010—much greater than Boston’s $125-or-so million, even accounting for the fact that LA’s population is nearly three times bigger:

How does China compare? Its cities now have about 200 cars per kilometer—the same traffic density as LA (paywall).

There are a few things China can do to fix this. Slashing emissions per vehicle is a crucial factor in bringing down mortality costs. That’s something Beijing has made progress on—it introduced strict new emissions rules in early 2013—though the city’s proximity to less environmentally-forward provinces is likely to severely dampen the impact.

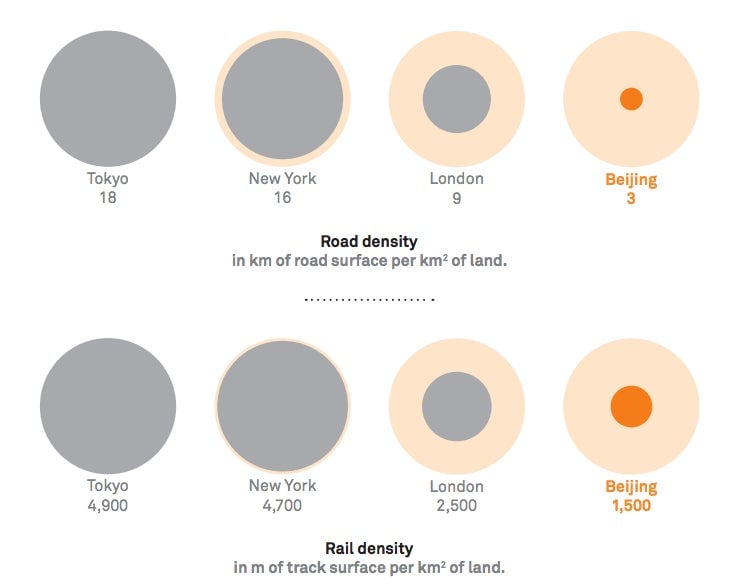

Investing in public transportation should help too, especially in smaller cities. However, even in a city as developed as Beijing, building more roads is even more urgent. Here’s how Beijing compares with other major cities:

A combination of these measures might work. A study by Georgia Institute of Technology’s Yang Jiawen found that China’s urban transportation patterns differ dramatically from those in the US. Instead of auto use increasing in suburban areas, in China, it’susually around a city’s center—concentrated in high-income areas (pdf, p.67).

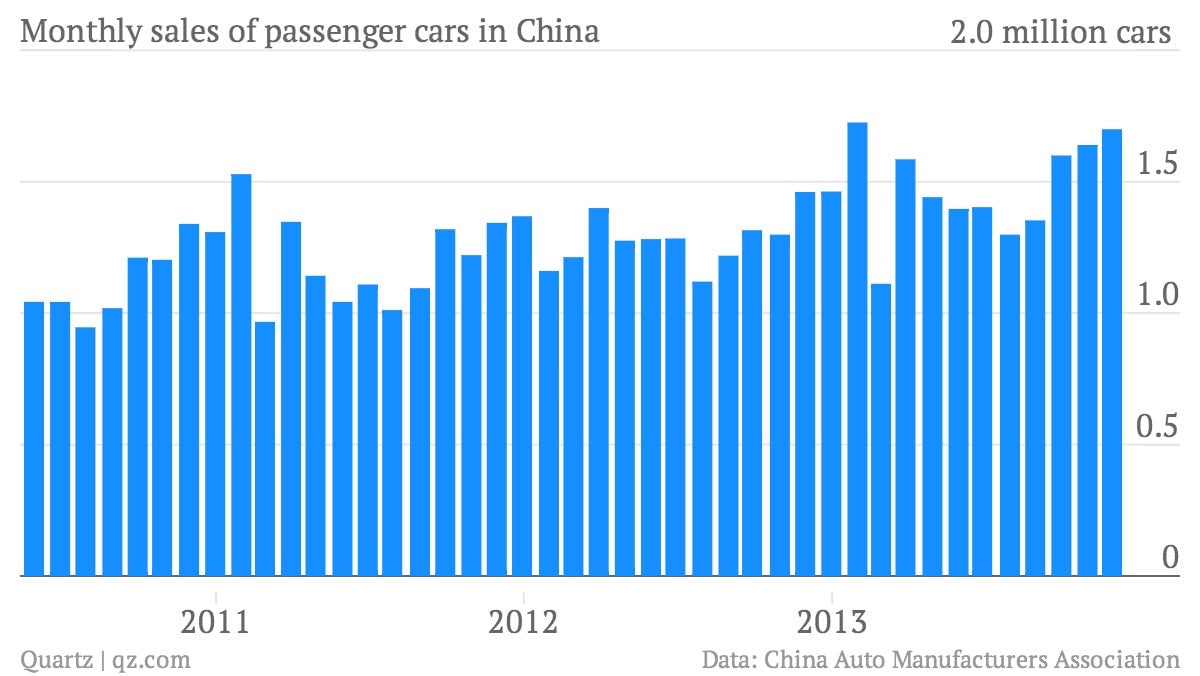

That helps explain why car sales are surging, even as air pollution-angst has exploded as well. In fact, sales of cars with bigger, more polluting engines boomed in cities mulling license-plate lotteries like that adopted in Beijing, as the WSJ reports. There’s only so much the government can do if its citizens ignore their own role in befouling the air.