A red-hot Chinese shopping-review app shows the future of your online shopping experience

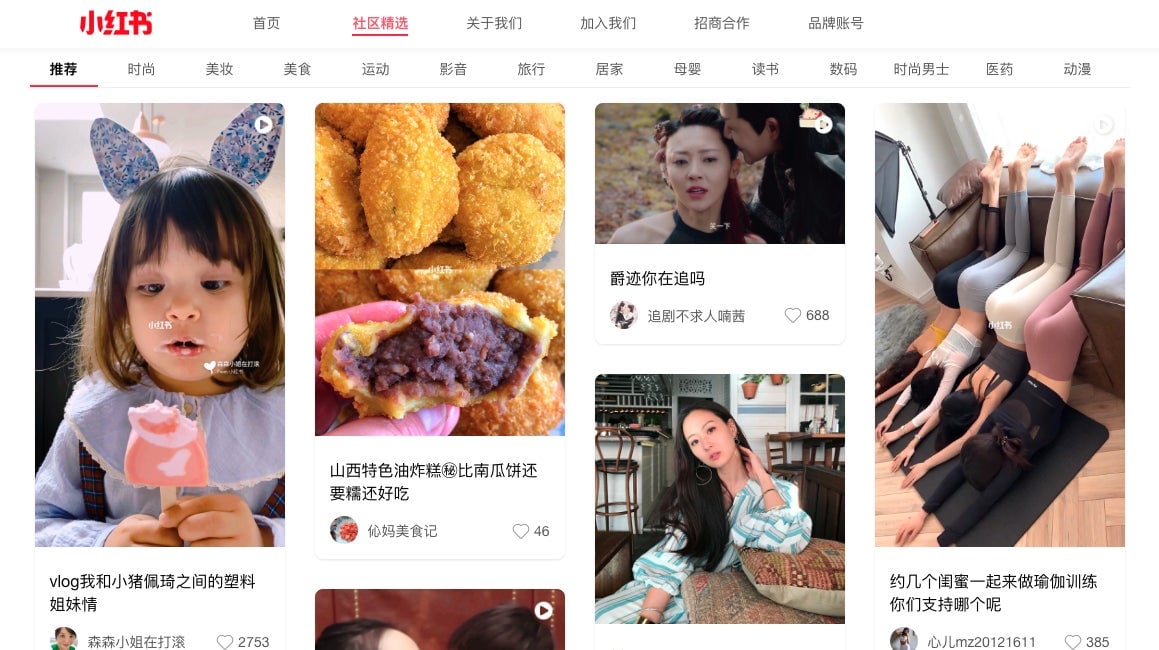

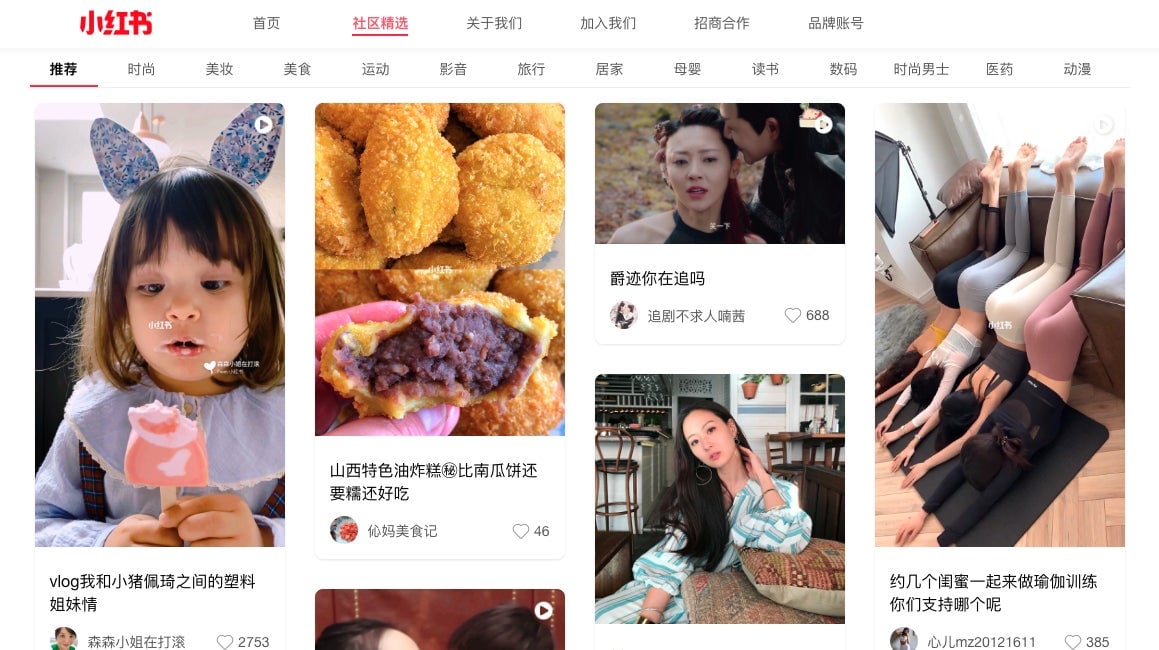

US tech companies are tinkering with social shopping—Facebook is adding online shopping features to its social network apps like Instagram, while investors are urging Pinterest to allow direct e-commerce (paywall) on the site. Those moves could bring users in the US a few steps closer to the deeply interactive experience of millennial online shopping in China, as experienced on social apps like the shopping-review community Xiaohongshu.

US tech companies are tinkering with social shopping—Facebook is adding online shopping features to its social network apps like Instagram, while investors are urging Pinterest to allow direct e-commerce (paywall) on the site. Those moves could bring users in the US a few steps closer to the deeply interactive experience of millennial online shopping in China, as experienced on social apps like the shopping-review community Xiaohongshu.

Founded in 2013 by Miranda Qu, who quit a well-paid job as a supply chain executive to start the business, and Stanford business school graduate Charlwin Mao—the two became friends after they bumped into each other at a Macy’s in Boston when she recognized his Wuhan dialect—Xiaohongshu began as an app to help travelers plan their overseas shopping lists. Its name translates to Little Red Book in English, but that’s not a reference to a title usually associated with Chinese leader Mao Zedong—the two have quite different names in Chinese.

Xiaohongshu’s founders quickly realized the app was being used for shopping advice by people who weren’t traveling anywhere, but were instead buying stuff via family, shopping agents or online. The following year, they added online shopping features, marking their entrance to China’s booming e-commerce market. The private company doesn’t regularly release figures for sales generated through its site, but in 2016, Wired reported the app had generated $200 million in annual sales.

While there are shopping platforms that easily dwarf Xiaohongshu—the app has something China’s biggest platforms don’t necessarily have: a community. It’s built that through its users’ copious “shopping notes” which detail every aspect of a product’s experience, rather than focusing on the purchase, delivery or return experience, more typical of reviews on large e-commerce sites.

The app has 85 million monthly active users, the company said this month (link in Chinese), as it marked its sixth anniversary. Together they generate more than 3 billion posts a day reviewing beauty products, clothes, restaurants, and services. In an internal letter this month (link in Chinese), the founders thanked its employees for helping users to “build this virtual city that belongs to them.”

“More people now want to go out and see the good life of the world,” wrote Qu and Mao. “And more people also want to make the good life they see in Xiaohongshu a reality.”

A “virtual city” showing millennials what’s out there

The desire to buy a product someone else has highly praised—known in Chinese with the portmanteau word “Zhongcao,” from the Chinese character grass, symbolizing something that grows rapidly—is a very common description when its users talk about Xiaohongshu, whose motto is “find the life you want.”

“It is so important that you see the product works for other girls well. You will have a feeling that you will be as beautiful as them if you buy it,” said 23-year-old Shan Wenran, a recent college graduate.

On Xiaohongshu, influencers range from well-known actresses—many of them there to post as consumers, not as paid influencers—to high-school students. The app’s users are mostly female, and young, born in the 1990s or later.

“Browsing Xiaohongshu gave me a chance to see the lifestyle of some impressive women my age,” said 21-year-old Li Wenxiao.

Xiaohongshu also brings Chinese celebrities closer to their fans. Actress Fan Bingbing has apparently joked that she should stop reviewing products on the app because they get sold out and she can never find them.

The female-focused social commerce app is now valued at $3 billion, after its last funding round with investors that included Alibaba and Tencent in June 2018. Looking at the bigger picture, social shopping in China is expected to reach 15% of online sales by 2022, up from 8.5% in 2017, according to research firm Frost & Sullivan.

Social commerce can range from recruiting friends for discounted group purchases, as on US-listed Pinduoduo, to livestreaming frenzied shopping expeditions (paywall), occupying a niche that has done unusually well in China by combining shopping and entertainment.

Last year, China’s online retail sales reached $1.33 trillion(9 trillion yuan), an increase of nearly a quarter compared with the previous year, according to the National Bureau of Statistics.

Finding its footing

It’s still hard for Xiaohongshu to find its place in China’s competitive e-commerce market where price matters more than anything. While it’s the second-most popular social networking app in Apple’s China app store, it ranked sixth for China’s online retail imports with a 3.7 % market share in the first quarter of 2019, according to a report by Chinese data analysis website analysys.cn, down from 4.3% a year ago. Alibaba’s Tmall alone accounts for about a third of the more than $50 billion (link in Chinese) of online retail imports, still a relatively small niche of e-commerce.

The far more price-conscious Pinduoduo, which offers very different kinds of goods and prices than Xiahongshu, has nearly 300 million monthly active users and generated $80 billion in transactions in its last financial year.

With users creating billions of posts a day, other recent changes in the app suggest the company’s worried the enormous number of reviews might actually be a hurdle to the app’s ability to get people to buy stuff. To cut down on paid posts that annoyed users, the company limited brand collaborations to users with significant followings. And last month it piloted a way to rate products using hearts, to help readers cut through the sea of information. Right now about half a million of its 250 million registered users can rate products.

Qu used the example of yogurt to explain why they launched the “Little Red Heart” feature (link in Chinese): “If you want to buy yogurt, there used to be 10 shopping notes or 100 related to it on Xiaohngshu before, but now there are thousands. You can’t read all of them.”

Still, users admit to using the app to window shop or research a purchase—and then buying it more cheaply elsewhere. Though hundreds of users commented and liked actress Yuqi Zhang’s stroller recommendation, one also noted that “the things she recommends are always so expensive.”

Li, for example, said she goes to large e-commerce platforms like Tmall and JD.com after she making her shopping lists with the help of Xiaohongshu. Her last purchase on the app was almost six months ago—when she bought an electric toothbrush for her mom as a gift when it went on sale. “The prices on Xiao Hongshu are usually higher,” she said.

Xiahongshu this month introduced live-streaming (link in Chinese), a feature already in some other popular shopping apps, which makes for a shopping experience that’s sort of mash-up of YouTube tutorials, Facebook Live, and Amazon.

“It’s a good way to close the loop between content and e-commerce. Because in the past [users] would just browse the content and go somewhere else to buy. But with live-streaming, there will be more clients to make a purchase on the platform,” said Ker Zheng, a consultant at Azoya, a Shenzhen-based cross-border e-commerce advisory.

Correction: This story earlier incorrectly referred to the Azoya analyst as Ker Zhang.