How sneakers became so valuable

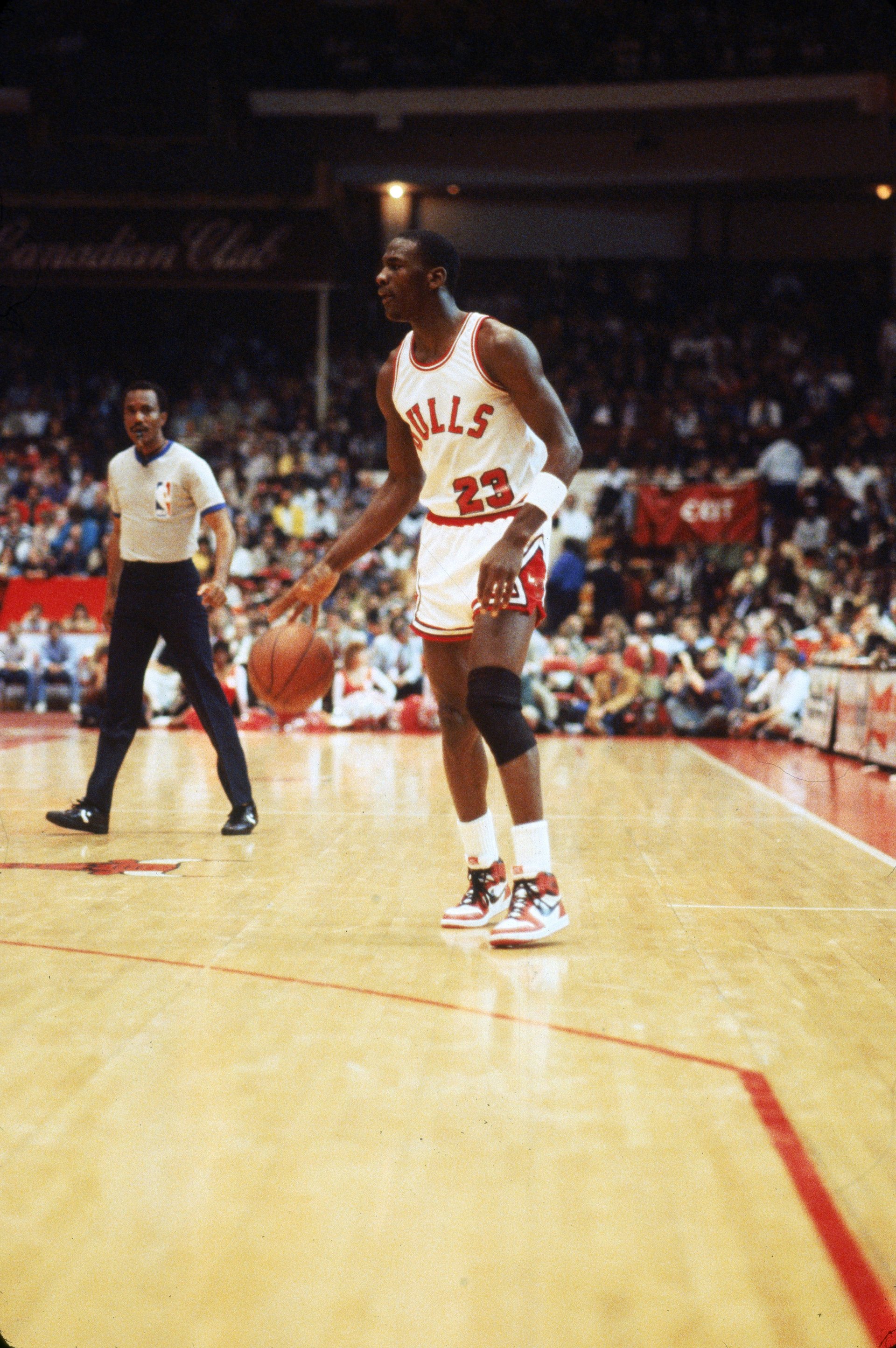

You could say 1985 is the year that modern sneaker culture really started. It’s when Nike publicly released its first signature shoe for a rookie basketball player named Michael Jordan.

You could say 1985 is the year that modern sneaker culture really started. It’s when Nike publicly released its first signature shoe for a rookie basketball player named Michael Jordan.

The Air Jordan 1 created a level of demand never before seen for a sneaker. Not only did Jordan quickly emerge as one of the most exciting players in the league, he did it in shoes that looked like nothing else on a basketball court. Players at the time wore sneakers that were basically plain white, maybe black. Nike wanted to create a shoe that was distinctive. The company used the colors of Jordan’s team, the Chicago Bulls, and made a sneaker in a striking combination of red and black that stood apart from everything else in the league. The coloring was so unusual that the NBA banned it, citing guidelines about player shoes having to match uniforms, even though the shoes were clearly in the Bulls’ colors.

Nike, which had struggled in the prior years and was in need of a hit, used the situation to its advantage. It had Jordan keep wearing the shoes and paid the fine every game. It also used the ban in its first commercial for the Jordan 1.

The conditions for the Jordan 1 were just right. Sneakers had started to emerge as fashionable status symbols in the 1970s. By the late 1970s and early 1980s, they’d become particularly valued on pick-up basketball courts and in the rising b-boy and rap scenes in New York, as Elizabeth Semmelhack, senior curator of the Bata Shoe Museum, explained in her book Out of the Box: The Rise of Sneaker Culture. This “urban” culture was quickly gaining popularity across mainstream America, boosting the cachet of owning the right pair of sneakers.

With the help of Nike’s marketing, the Jordan 1 was an immediate success. “The first Air Jordan made more than $100 million in the first ten months, and effectively turned the company around,” Semmelhack wrote.

Other shoes were important in sneaker culture as well, including Nike’s Air Force 1 and Adidas’s Superstar, a staple in hip-hop that rap group Run-DMC made into an icon with its 1986 song “My Adidas.” But Nike made another unusual move: It serialized the Jordan line. In 1986 it put out the Jordan II, and then in 1988 the Jordan III—the first of a series of Jordans designed by Tinker Hatfield, recognized today as one of the greats of sneaker designer—and so on. Over time, styles such as the Jordan III that were popular on release would become hard to get, creating demand. In 1994, Nike reissued it, and laid the foundation for the model of retros and limited releases that many sneaker brands use today.

Every week there are new drops of shoes that people scramble to buy. Many invariably fail. A lot of those who succeed list the shoes on the secondary market for a big markup over the retail price.

If it wanted to, Nike could keep the market full of Jordan IIIs and every other Jordan model to make sure it got the money of anyone wanting to buy a pair. For the most part, it hasn’t. (In the past few years, it did increase distribution of Jordans, creating a surplus that hurt resale prices. Nike has since pulled back on distribution again.) Typically, it has left people wanting more than are available, maintaining demand for the shoes. It feeds that demand by occasionally releasing new colorways or retros. Other companies do the same.

John Kernan, an analyst at investment firm Cowen, which issued a report in April on the sneaker resale market, notes in a video tied to the report that Nike’s and Adidas’s sales have been growing significantly above their inventory levels for two years, creating a “pull market” for their shoes. “We think this is ultimately feeding back into the resale market,” he says.

Josh Luber, cofounder and CEO of online resale marketplace StockX, says he isn’t worried about the sneaker bubble bursting either. He argues that previous consumer goods crashes, whether it was tulips in Holland in the 1630s or Beanie Babies in the US in the 1990s, happened because of a lack of transparency into the true supply and demand for those products. StockX and the internet provide that transparency into sneakers. It’s also in the interest of the big sneaker players to manage how much they release. They’re biased toward keeping demand high in the long term, so they will continue controlling the supply of shoes available, which should keep the resale market thriving.