A new Trump plan to deny migrant kids education and lawyers is illegal

A government plan announced this week to stop providing thousands of detained migrant kids with education and legal representation would contravene not only US law, but the US Constitution as well.

A government plan announced this week to stop providing thousands of detained migrant kids with education and legal representation would contravene not only US law, but the US Constitution as well.

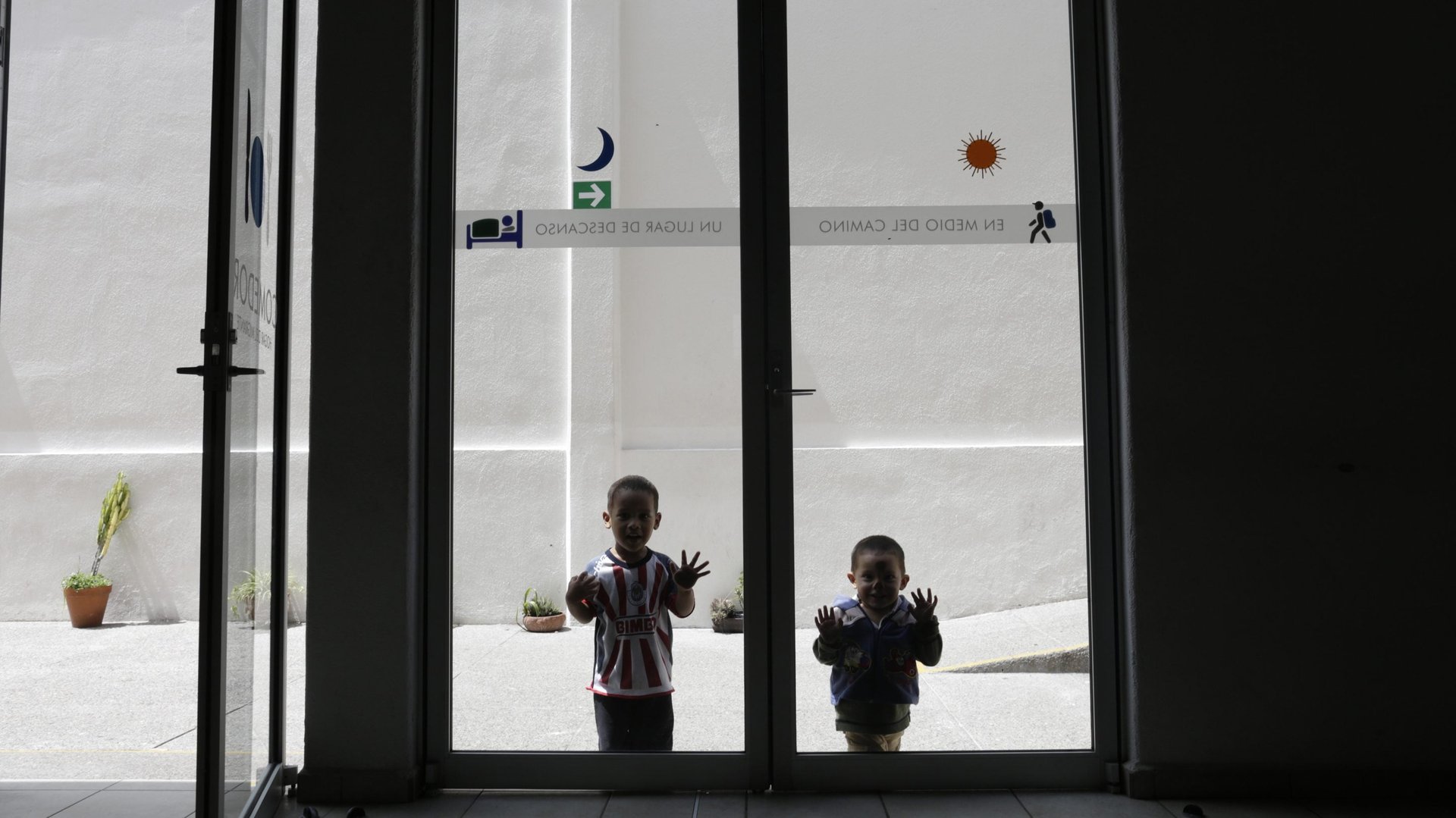

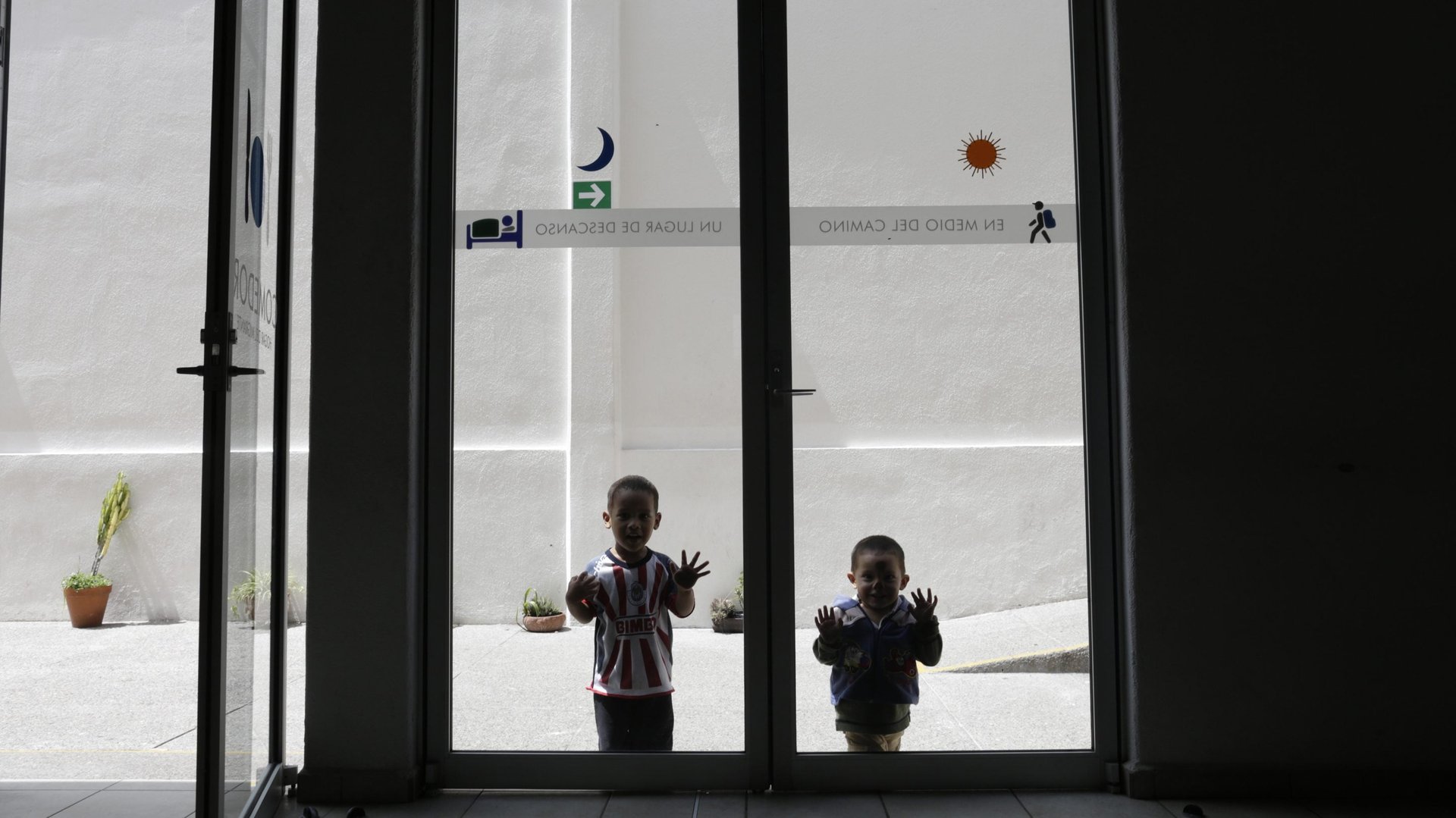

A spokesman for the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), which in April held 12,500 kids in custody, told Quartz the department is defunding activities “not directly necessary for the protection of life and safety, including education services, legal services, and recreation.”

Multiple immigration attorneys said that denying these kids education and legal representation is unquestionably illegal. But the HHS told Quartz it is relying on an obscure, never-tested legal loophole and special permission from the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) to make the change.

Migrant kids’ rights

As Quartz’s Ana Campoy outlined last year, the US government has a number of conditions it must fulfill if it detains migrant children. These conditions are the result of the 1997 settlement of a 1985 court case called Flores v. Reno. Immigrant advocates filed the case against the government, questioning its treatment of immigrant children. The result was a specific set of guidelines for the way the government treats migrant kids. Since then, the government has been sued multiple times for failing to adhere to the settlement. Meanwhile, Congress has passed additional laws protecting migrants kids.

The ACLU says that for children in detention, “the governing US legal standards come from various overlapping sources.” Among other things, the government is required to provide both education and legal representation to migrant children. Campoy wrote:

Aside from being “safe and sanitary,” the facilities must, for example, provide routine medical and dental care, as well as education in a structured classroom setting. That should include English language training, as well as the provision of reading materials in the detained children’s native languages. The centers should also offer kids counseling, and a “a reasonable right to privacy” to talk on the phone and store their belongings.

Asylum-seekers rights

A long-established precedent, settled by the Supreme Court in 1896, says the US guarantees anyone in the country the protection of the US Constitution and due process, including immigrants who arrived here illegally, as Quartz’s Annalisa Merelli wrote last year:

[A]ll persons within the territory of the United States are entitled to the protection guaranteed by those amendments, and that even aliens shall not be held to answer for a capital or other infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a grand jury, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law.

According to the UN’s Convention on the Rights of Refugees of 1951, and the Protocol subsequently ratified by the United States in 1967, there are legitimate cases in which a refugee might breach a country’s immigration law in order to apply for asylum (pdf, p.3).

Yet the US government is forcibly removing kids from their families at the US border and detaining them, even as they claim asylum. The Trump administration has tightened policies on who qualifies as a family member and has moved to deport undocumented family members who claim children, which is leading to more kids in custody.

The ADA loophole

The US government knows all this, of course. So they found a possible loophole. Evelyn Stauffer, a senior advisor for the HHS division called Administration for Children and Families, emailed Quartz a lengthy statement about its plans. She pointed to this specific explanation:

The Antideficiency Act (ADA) requires that appropriations be managed to prevent the obligation of funds at a rate that indicates a necessity for a deficiency or supplemental appropriation (31 USC 1512). The Act includes limited exceptions to that requirement, including one where additional obligations are necessary for the safety of human life or to provide legally required support to individuals (31 USC 1515). The latter provision requires a deficiency apportionment from OMB to make it permissible to obligate an appropriation at a rate that indicates the need for a supplemental or deficiency appropriation. HHS has requested and received a deficiency apportionment from OMB, and OMB has reported the deficiency to Congress.

The Antideficiency Act, first passed in 1884, essentially prohibits any US agency from spending money that it doesn’t have. During the record-long shutdown this past winter, there was speculation that some still-running agencies could be forced to violate the act. But no agency has ever actually been charged with violating it and the issue has never been litigated in all of American history.

That is likely to change. Children’s rights activists, including Peter Schey, said they plan to challenge the move in court.