The first rule of CBD marketing: Don’t mention “cannabis”

On a spring evening in Los Angeles, Michael Bumgarner, the co-founder of the personal care brand Cannuka, addressed a dinner party of women about cannabidiol—a key ingredient in his company’s lotions, soaps, and balms. The chemical compound more commonly known as CBD comes from cannabis, a plant that also goes by marijuana, pot, weed, ganja, and countless other names. But Bumgardner was determined to draw a distinction between that illicit stuff and his source material.

On a spring evening in Los Angeles, Michael Bumgarner, the co-founder of the personal care brand Cannuka, addressed a dinner party of women about cannabidiol—a key ingredient in his company’s lotions, soaps, and balms. The chemical compound more commonly known as CBD comes from cannabis, a plant that also goes by marijuana, pot, weed, ganja, and countless other names. But Bumgardner was determined to draw a distinction between that illicit stuff and his source material.

“Think about the canine family—you have a poodle and you have a wolf,” he said. “You don’t want to mess with the wolf if you’re not ready for the wolf … CBD is the poodle. It’s the smartest dog!” And it’s de-clawed.

“The wolf” of course, is cannabis—the kind that gets you high, that we were told to “Just Say No” to, and that for nearly a century has been a weapon of racial discrimination at the hands of the US criminal justice system.

Eight decades after the release of Reefer Madness and the emergence of the tactics that gave way to the US War on Drugs, the producers of CBD products in the US are pulling off a staggering feat of rebranding. CBD is helping cannabis slip its political and historical baggage, and re-emerge innocent and virtuous, as a product that’s more wellness than weed; more approachable than subversive; more poodle than wolf.

But is that a good thing?

CBD is one of many chemical compounds in a class called “cannabinoids” that naturally occur in cannabis plants. The other one you’ve likely heard of—and was once far better-known than CBD—is tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC. While THC is both feared and revered for its ability to get users high, CBD is beloved, in part, because it doesn’t. But CBD does promise relief from a smorgasbord of scourge-like symptoms—stress, anxiety, joint pain, inflammation, and insomnia among them. That promise is leading to a CBD boom: Some market researchers predict the market for CBD in the US will have increased nearly tenfold between 2018 and 2019, from $590 million to $5.7 billion.

When I asked Vivien Azer—the first major Wall Street analyst to begin covering the cannabis industry—what she found most exciting about CBD, she didn’t miss a beat:

“It could very well have the potential to ultimately help de-stigmatize the broader cannabis category,” she said.

A catastrophic campaign: America’s War on Drugs

That’s some serious stigma to undo. For decades in the US, cannabis was the focus of one of the most catastrophic branding campaigns of the modern era: the War on Drugs.

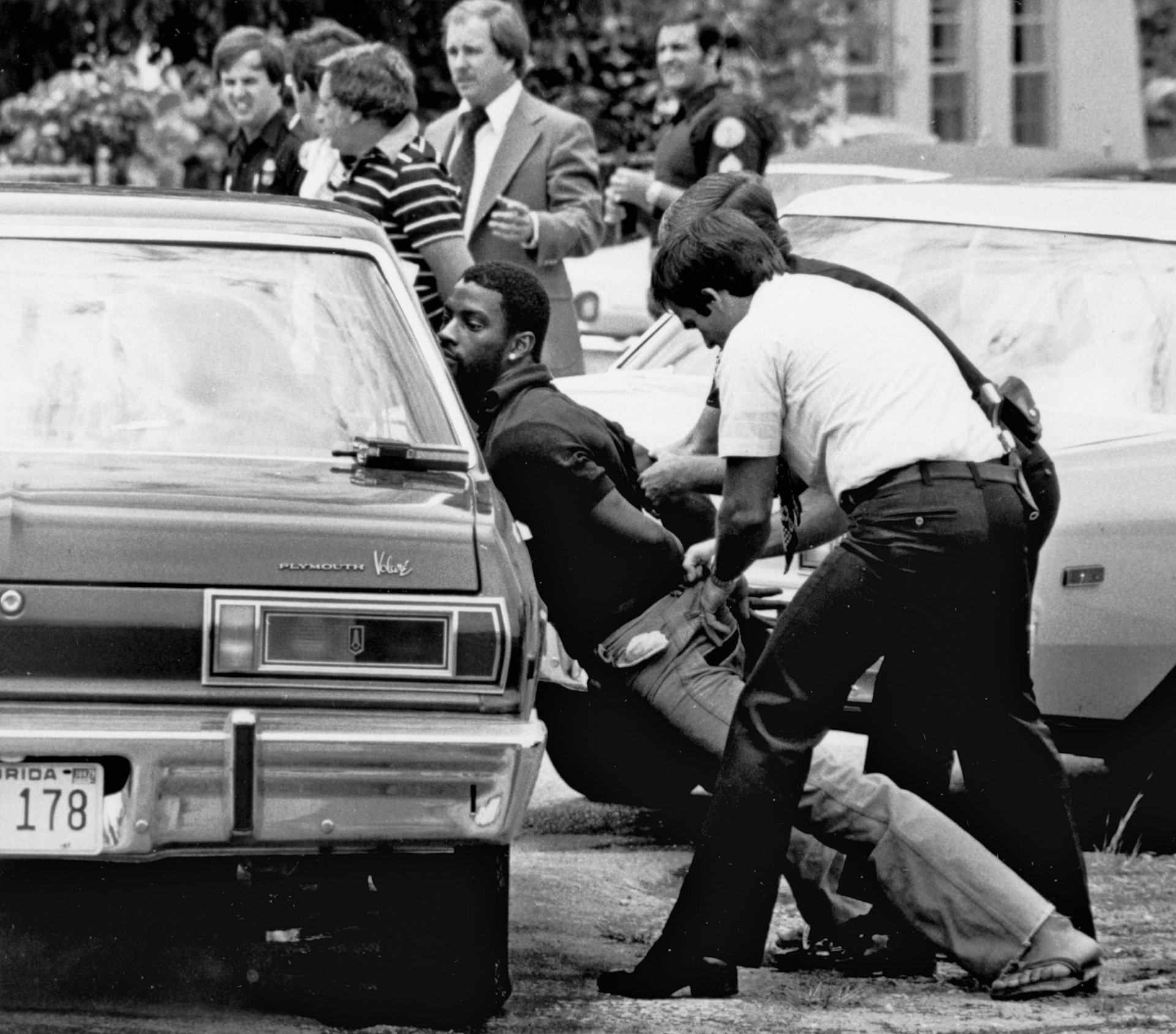

Established by US president Richard Nixon in 1971, and carried on by president Ronald Reagan with the help of his wife Nancy’s “Just Say No” campaign, the federal initiative demonized drugs—including cannabis—and led directly to the US’s incredibly high incarceration rate, the world’s worst. Nixon also presided over the Controlled Substances Act, which classified the plant as a Schedule I drug with the highest risk of abuse and least medical potential, and criminalized its possession, use, and sale as a federal offense. Between 1980 and 1989, the arrest rate for drug possession and use nearly doubled. And although surveys show that whites use drugs as much or more than blacks in the US, black people were arrested for drug-related offenses at five times the rate of whites in the late 1980s and early 1990s. (Indeed, John Ehrlichman, the former domestic advisor to US president Richard Nixon, has admitted the policy was designed to undermine black communities and the political left.)

But the roots of the War on Drugs go back further than that, thanks to Harry J. Anslinger—a noted racist and staunch cannabis opponent who became the US’s first Federal Bureau of Narcotics chief in 1930, and stayed in the job for more than 30 years. Anslinger drafted the 1937 Marijuana Tax Act, which would federally regulate cannabis in the US for the first time, and effectively criminalize it. (Within a year of the law’s implementation, the director of the Federal Bureau of Prisons blamed it for overcrowding in US prisons.)

He had the help of a hefty propaganda campaign. As Eric Schlosser wrote, anti-cannabis campaigners connected “the evil weed” with bloodthirsty criminals and fearsome immigrants. Half a century before my generation saw an egg sizzle on a skillet and heard “this is your brain on drugs,” the film Reefer Madness linked cannabis use to rape, murder, suicide, and insanity.

In December, the US government made a distinction between CBD and the rest of the cannabis plant, when president Donald Trump signed the 2018 Farm Bill, which explicitly removed hemp-derived CBD from Schedule I, where it was lumped together with heroin and LSD. Hemp, as defined by the Farm Bill, contains less than 0.3% THC. Any more than that, and the plant becomes marijuana in the eyes of the law—which is still a Schedule I substance despite having a better safety profile than alcohol.

An alternate narrative

For decades in the US, cannabis was linked to images of dropouts, stoners, welfare moms, and drug dealers. Then, in 2013, CNN chief medical correspondent Sanjay Gupta delivered Americans a near-perfect alternate narrative.

With the first episode of his documentary series, Weed, Gupta visited the home of Paige and Matt Figi, a white Colorado couple whose five-year-old daughter Charlotte was suffering from Dravet Syndrome, a severe and potentially fatal form of childhood epilepsy. While Matt was deployed in Afghanistan, his daughter’s condition was in sharp decline; she was plagued with hundreds of seizures a day, and saw little relief in the vast array of pharmaceuticals her doctors had prescribed. Although Matt had never smoked cannabis himself, he had read online about cannabidiol’s potential to provide relief from seizures, and sent his wife on the hunt for a high-CBD strain of medical marijuana.

Enter Josh Stanley, a Colorado grower with a greenhouse full of the stuff, who met Charlotte and said the Figis could pay what they could afford.

“People have called us the Robin Hoods of marijuana,” Stanley tells Gupta of himself and his six brothers, his blue eyes welling up. “They say that we sell pot so that we can take care of the kids, and the truly less fortunate.” Cut to five-year-old Charlotte, down to a single seizure per week from 300, happily painting and reading with Gupta.

Today, Charlotte is twelve and still nearly seizure-free, the company founded by the Stanley brothers, Charlotte’s Web, is the US market leader in hemp-derived CBD and publicly traded in Canada, where its valued at about $CAD 1.83 billion ($1.36 billion), and Gupta has become one of the strongest voices of support for legal access to cannabis.

Rebranding cannabis

“Accessibility is the word of the day, as [CBD] products roll out to the mainstream,” says Paul Earle, a branding expert who teaches corporate innovation at Northwestern’s Kellogg School of Management and has worked for clients including Procter & Gamble, McDonald’s, and E&J Gallo. “If you want to create a big accessible, relevant, and thriving new brand, you’ve got to start creating new iconography and new language around it.”

That means steering clear of past design orthodoxies, says Earle, avoiding “hippy-dippy” language and imagery that might recall cannabis’s past—or even the plant itself.

“Removing the word ‘cannabis’ from ‘CBD’ is a key to the success of CBD as a branded space,” says Earle. “I wouldn’t lean in too hard on leaves, for example, as visual icons.”

Instead, he says, innovative new cannabis brands are applying clean modern design to their products, and in the most sophisticated cases—such as the CBD seltzer brand Recess—”leveraging the mystique, intrigue, and otherworldly appeal, without making everything feel like an art poster from Haight Ashbury in 1968.”

Earle knows a thing or two about creating a new category with branding. He was part of the founding team of Angel’s Envy, the premium bourbon brand that was acquired by Bacardi in 2015, and says there are parallels between CBD and the bourbon resurgence of the 2000s, when sales of the priciest bottles nearly quadrupled. With Angel’s Envy, he says, “we wanted to avoid any bearded white guy born before the year 1900 in the design.”

Today, as an advisor to a forthcoming CBD brand, he’s following a similar playbook. “You will not see tie-dye shirts anywhere. You will not see a cannabis leaf anywhere. You will not see the old stereotypical picture of the guy with his eyes bugging out.”

As a spirits veteran in the cannabis space, Earle is not alone. He says in addition to the big players such as Constellation Brands, he sees fellow entrepreneurs from the bourbon boom stealthily investing in CBD.

“They see the exact same opportunity to use sophisticated design, beautifully crafted products, and a change in nomenclature and tone to open up the floodgates to a much bigger market than what previously existed,” he says. “What we want to do as marketers is either completely avoid—or possibly openly confront and disarm—all of the past taboos regarding these kinds of products.”

In other words, to make cannabis mainstream, CBD marketers are treating it like Fight Club: The first rule of cannabis is, you do not talk about cannabis.

Telling the whole story

But in avoiding the plant’s “past taboos,” are CBD marketers helping to reinforce them?

Kimberly Dillon, the former marketing chief for the California-based cannabis brand Papa & Barkley, who today consults for other cannabis and CBD brands says that’s a real risk.

“The way CBD is marketed—in a way where it’s so detached from the plant, the activism, and the movement—positions the smoking of cannabis as bad,” Dillon wrote for AdWeek in April. “CBD is just a touch naughty, but THC—that’s outright bad. As a result, every brand is tripping over themselves to offer wealthy soccer moms a CBD gummy.”

“It’s pastels and clouds and puffery and ‘everyone rest easy,'” Dillon told me recently over the phone. “There’s a way to make [CBD] accessible … but it can’t be at the expense of erasing social justice issues—and not at the extent of demonizing cannabis and THC.”

After all, those past taboos are still connected to a very real present; the US War on Drugs is far from over. In 2017, the drug-related arrest rate for blacks was still more than double that of whites, and a study by the National Registry of Exonerations found that blacks were five times as likely as whites to go to prison for drug possession. In some big cities, the statistics are even worse. In 2018, blacks and Latinos accounted for nearly 90% of arrests for smoking cannabis in New York City.

And cannabis—with its many complex cannabinoids, including both CBD and THC—has provided real medical benefits to countless patients for centuries.

Julie Baker, the marketing director for Epidiolex—the first cannabis-derived drug approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)—said she thinks the popularization of CBD has been detrimental to the plant’s acceptance as serious medicine.

“I think we’re in the beginning of the backlash,” said Baker at the Cannes Lions advertising conference on Tuesday.

“A lot of people, especially in the medical community were really skeptical about CBD,” she said. “They associate it with pseudoscience and fluff. And Kim Kardashian isn’t helping. Her fourth baby shower was CBD-themed.”

So rather than using the current CBD playbook and leaving the plant outside the story, Baker and Epidiolex, a fruit-flavored liquid prescribed to treat seizures in children with severe epilepsy, went in the other direction: extreme transparency. Once the drug was approved, the company partnered with New York-based creative agency The Bloc to create an all-access virtual reality tour of Epidiolex’s production process—from hazmat-suited men checking plants in sprawling grow-houses outside London all the way to the bottling facility.

“Nothing engenders trust like transparency,” said Baker.