Having this many 2020 US Democratic candidates is not a bad thing

There’s been recent postulation that that having a plethora of Democratic presidential candidates—all 24 of them—will have a profoundly negative effect on voter turnout in 2020.

There’s been recent postulation that that having a plethora of Democratic presidential candidates—all 24 of them—will have a profoundly negative effect on voter turnout in 2020.

The theory is straightforward: Because our brains are lazy and try to limit the attentional resources we spend on decisions, we often fall victim to choice overload; the greater the array of options, the less likely we are to act, and the lower our satisfaction when we do. Thus, the more candidates, the greater the choice overload, and the lower the voter turnout. Simple.

And wrong. If you look at the voter turnout for presidential elections from 1980 to 2012, there is no correlation between the number of candidates running and voter turnout in elections. Ditto for congressional elections in the same period. This fact holds true when you look at candidates who actually declare and appear on a ballot (a smaller number, courtesy of the United States Election Project) or those who appear on polls (a much larger number, courtesy of FiveThirtyEight). No matter what, more candidates doesn’t appear to correlate to lower voter turnout.

But why not? The choice overload effect is very robust and has been replicated by behavioral scientists many times over. When there are too many choices, particularly choices that are difficult to tell apart, people tend to be less likely to make a decision and less happy with the decision they make. So why aren’t we seeing the hypothesized reductions when it comes to voter turnout?

Choice overload is what we call an “inhibiting pressure,” which reduces the chance that people will behave in a particular way. But inhibiting pressures can be overcome by “promoting pressures,” which make a behavior more likely. Remember Desiline Victor, who at the age of 102 waited in line for three hours to vote for Obama in 2012? It wasn’t that waiting wasn’t hard (a weak inhibiting pressure) but that voting was so important (a strong promoting pressure) that made her stick it out. “I did what I had to do to vote for my president,” she said.

That’s why having more candidates doesn’t reduce voter turnout—or increase it, for that matter. At least so far, the additional inhibiting pressure of choice overload has been balanced against the promoting pressure of having a candidate who is worth choosing—someone who is worth waiting three hours in line to vote for. Someone who represent voters’ values and their self-identity, no matter how they define them. What a wide field of candidates does is increase the likelihood that voters can find one to consider truly theirs.

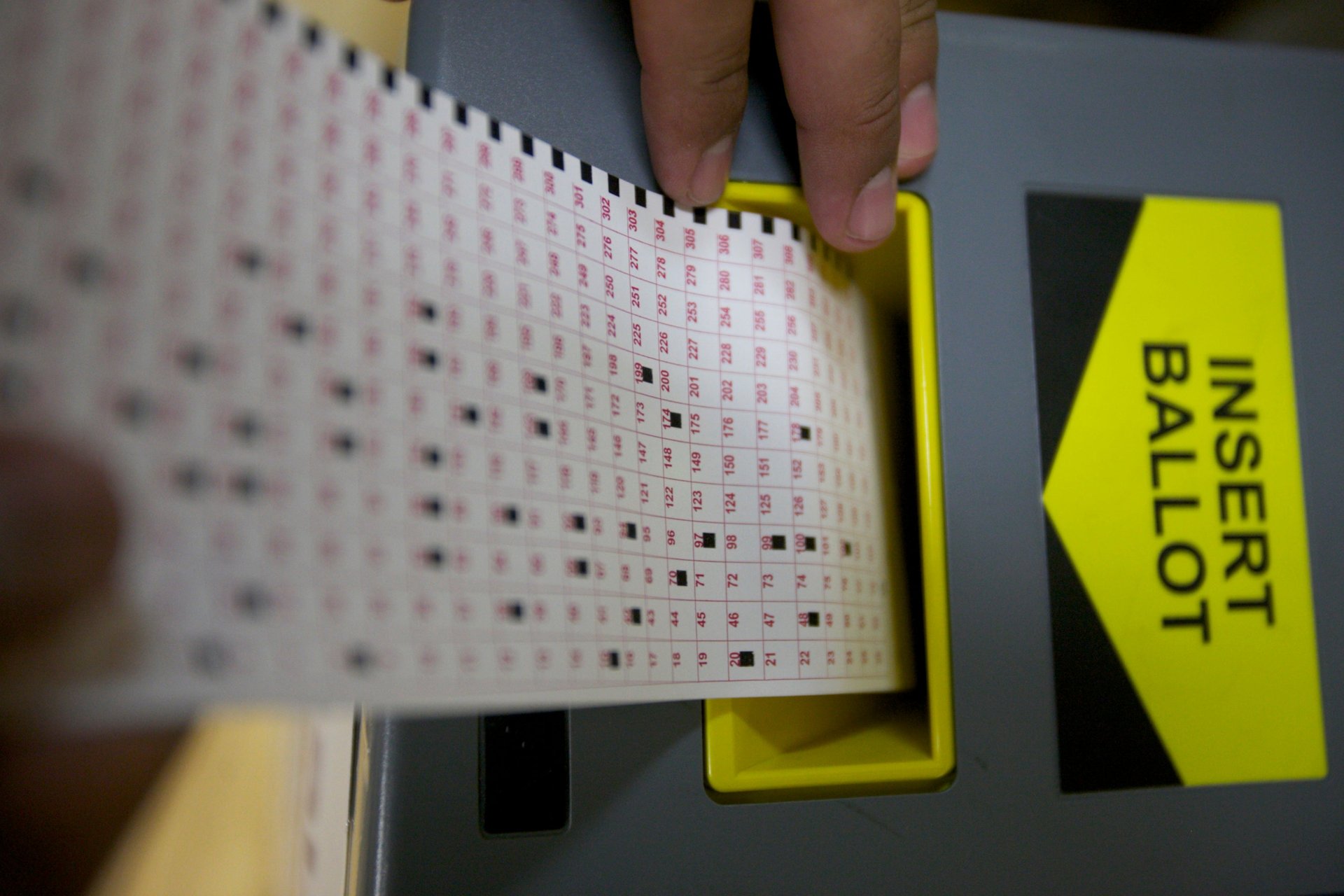

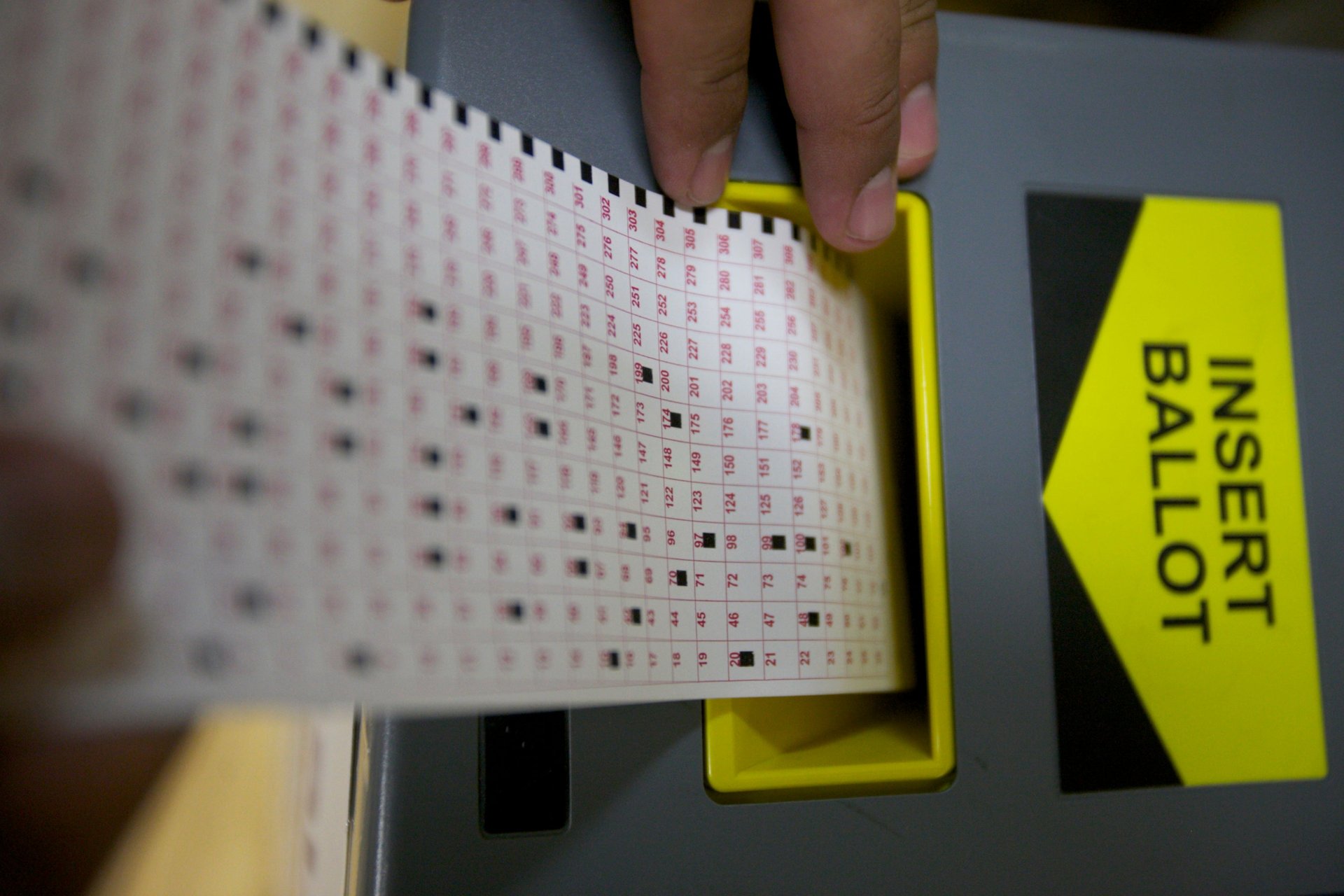

And that’s behavioral science: Behavior as an outcome, science as a process. We don’t have to rely on theory when it comes to voter turnout, because we can actually test interventions that change the balance of pressures and the resulting behavior. By consciously designing our voting process to reduce inhibiting pressures and strengthen promoting pressures, we can better our democracy.

And we already know how to do it. The list of pressure-modifying interventions that need to be rolled out federally is seemingly endless. Based on results from my home state of Oregon, automatic voter registration alone would result in 7.9 million additional voters nationwide by reducing a needless inhibiting pressure. Canvassers who work in communities to increase promoting pressures to vote could drive an additional 6.2 million voters.

So instead of expressing shock and dismay at a candidate field so large that it requires not one but two nights of debate (Two whole nights? For the highest political office in our country? Say it ain’t so!), why don’t we instead celebrate the desire of so many people to participate in the civic process? If we make voting our behavioral outcome and design consciously for it, we can manage choice overload and help create a new norm: voting for a candidate who actually represents the dominant beliefs of our country.