Happy Asteroid Day! NASA still can’t track the ones that could end civilization

The United Nations would like you to be aware of asteroids. I’d like you to be aware of this: We—us humans—don’t know even know where all the threatening asteroids are.

The United Nations would like you to be aware of asteroids. I’d like you to be aware of this: We—us humans—don’t know even know where all the threatening asteroids are.

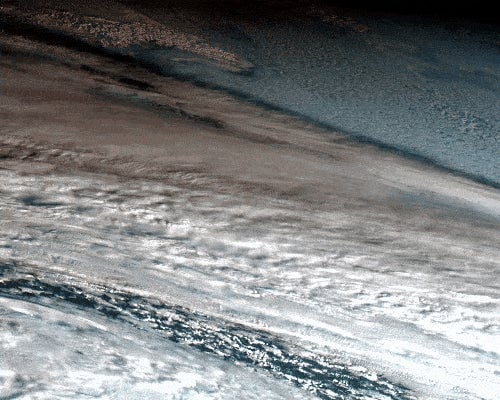

June 30 is the day for this kind of activity because on this day in 1908, an asteroid exploded over Tunguska, Russia, destroying hundreds of acres of forest. There are more recent examples: Last December, a larger asteroid broke apart over the Bering Sea with force 10 times more powerful than the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima. It wasn’t tracked in advance, but a NASA satellite accidentally captured imagery of the fireball from space:

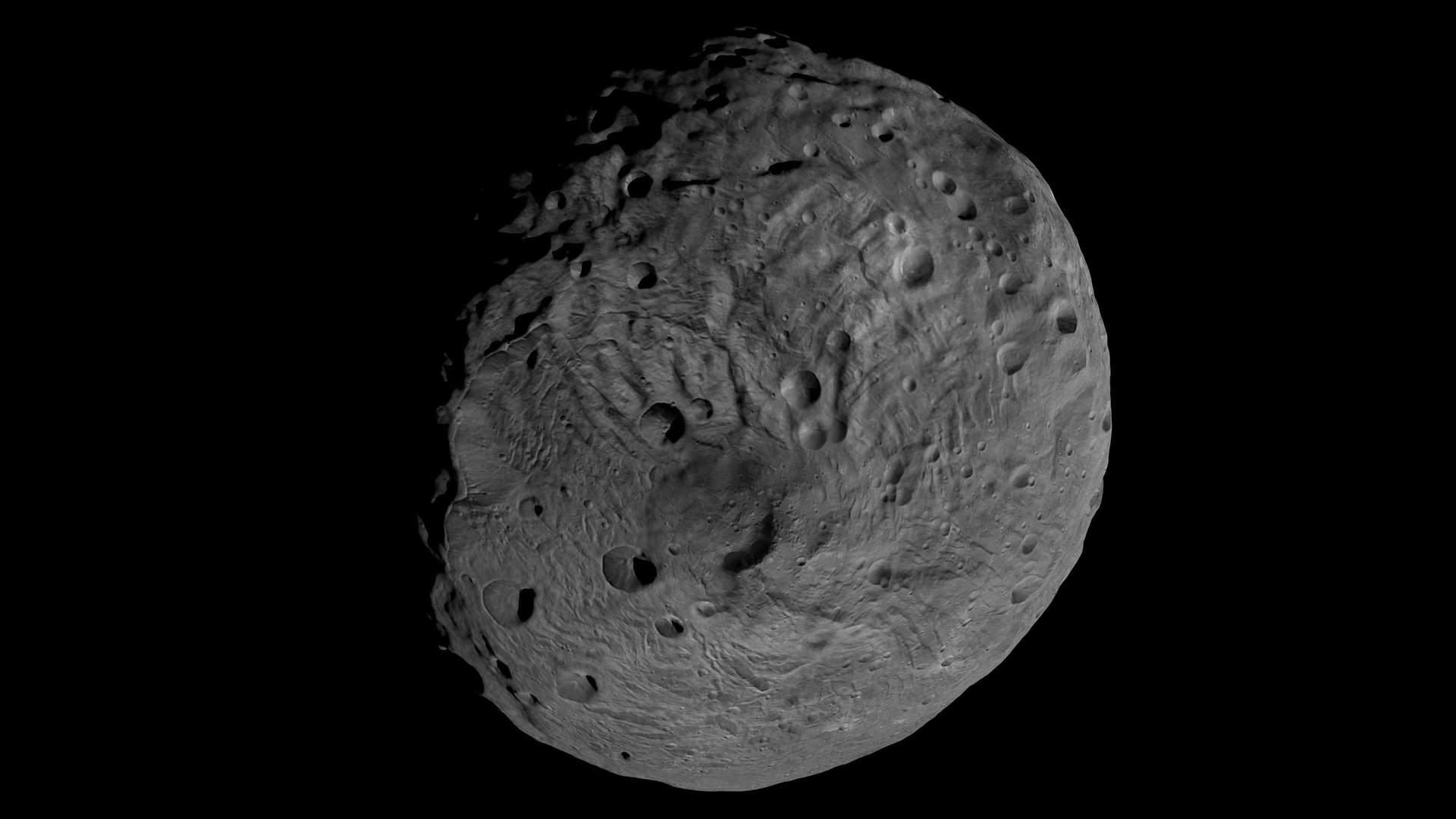

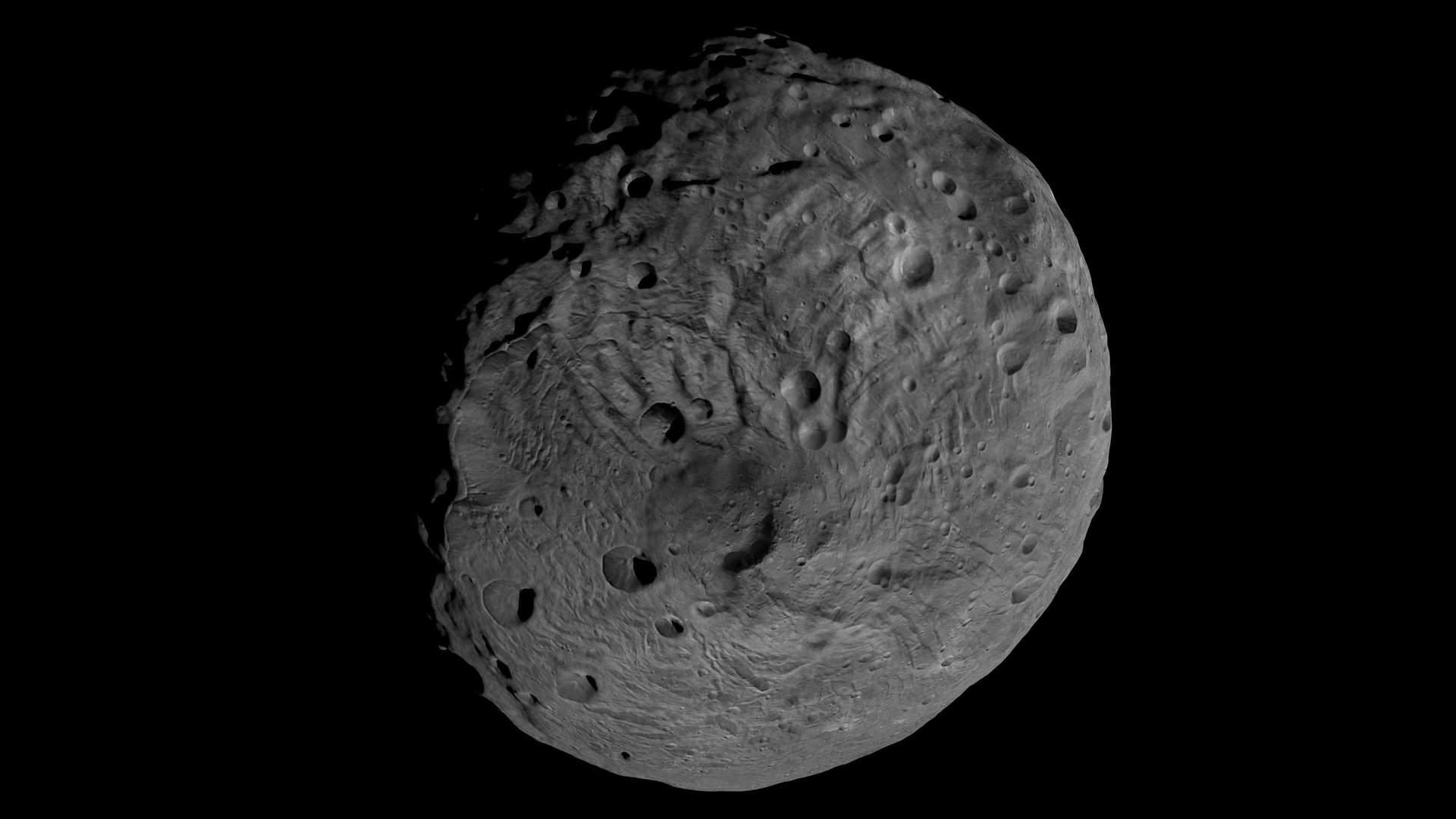

Naturally, astronomers have set out to find the asteroids that might intersect with Earth. They’ve found more than 8,000 so far, but researchers believe that is only a third of the asteroids that might come near our planet. Thankfully, most of the asteroids larger than the one behind the extinction of the dinosaurs have been found. But if astronomers are correct, there are still thousands more in the solar system that could devastate cities or entire regions if they were to impact the Earth.

The politicians got involved, too, with the US Congress passing a law in 2005. The law required that NASA find 90% of near-Earth objects (that’s the term of art here) that are larger than 140 meters in diameter by 2020. We’ve known for a few years now that NASA isn’t going to make the deadline. They just don’t yet have the tools yet to find all these asteroids.

One option will be the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope, or LSST, built around a tennis court-sized mirror on a mountain in Chile. In 2023, the telescope will begin a 10-year survey that researchers expect will find about 75% of the largest near-Earth objects.

But there will be more to find, and that will require a space telescope, according to a new report from the National Academy of Sciences. It concluded that infrared sensors in space would allow asteroids passing close to Earth to be identified quickly. Infrared sensors are also unique in being able to more quickly figure out the size of an asteroid: In the spectrum of visible light, astronomers have a hard time distinguishing between large, dark objects and small, bright ones, but thermal data collected at infrared wavelengths can be used to solve that problem.

The obvious choice here is NEOCam, a space telescope proposed by a team of scientists led by Dr. Amy Mainzer, who has been studying asteroids and designing sensors to find them for nearly 15 years. “You’ve got to go out and look with the right tools to let them see the things, far before they are on the Earth to have a close encounter,” she told me in April. “The question is, when is the next one going to happen on a human time scale as well as a geological time scale?”

At a hearing in March, NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine suggested that the recently-launched TESS telescope may help fulfill the mandate, but said it would be followed by a launch of the NEOCam mission. “The evidence is clear—the dinosaurs did not have a space program,” he told senators. “We do. Therefore we need to be prepared to do what is necessary to protect our planet.”

NASA planetary defense officer Lindley Johnson has said it would take a decade of warning to prepare a mission to avert a deadly asteroid. In April, he said that the space agency was waiting for the completion of the NAS study before green-lighting NEOCam as a full-fledged mission. With the report now complete, Mainzer says her team has yet to receive the go-ahead to proceed with the next phase of development from the space agency.

The public, however, has a preference. A May 2019 poll by the Associated Press and the National Opinion Research Council found that 68% of American adults supported programs to track asteroids, making it the top priority for NASA activities, particularly compared to human missions to the moon or Mars.