What Huawei tells us about Trump, trade, and technology

Even by his own rhetorical standards, Donald Trump’s trade war policies don’t make a ton of sense. The president says his confrontation with China is about trade (see: his repeated complaints about the US-China trade deficit and his use of punitive trade barriers). But the core of the conflict isn’t really about trade at all. It’s about technology.

Even by his own rhetorical standards, Donald Trump’s trade war policies don’t make a ton of sense. The president says his confrontation with China is about trade (see: his repeated complaints about the US-China trade deficit and his use of punitive trade barriers). But the core of the conflict isn’t really about trade at all. It’s about technology.

The administration’s biggest beef with China is that it steals US intellectual property and practices an industrial policy that advantages Chinese technological companies. So it’s about demanding fairness and free competition, right? Increasingly, it seems, not so. Trump’s recent actions suggest his goal is a nationalistic approach to economic development—one that swivels on shielding US technological dominance from Chinese ambitions.

It’s no coincidence that the one company that illustrates these tensions best is now trapped in the middle of the US-China trade war.

Right in the bullseye

Huawei boasts the distinction of being perhaps the only Chinese company that’s a true global technological leader—one that outcompetes on both quality and cost. Now the world’s top supplier of telecom equipment, the Shenzhen-based firm has built more than 1,500 networks in 170 countries asnd regions. Its phones are also first-rate—which is why, last year, it sold more smartphones than Apple, and trails global leader Samsung only slightly. That success translates to Huawei’s appetite for cutting-edge hardware and software from some of America’s top tech companies—Qualcomm, Intel, and even Google, to name a few.

In May, the Trump administration dragged Huawei into the midst of its trade war when it banned US companies from selling it their products—a potentially extinction-level threat to the firm’s business—on the basis of national security. Then suddenly, in a move that reportedly caught even Chinese officials by surprise (paywall), Trump said he would ease restrictions on Huawei, in exchange for increased Chinese purchases of American agriculture and resumption of trade negotiations.

Whether this results in the deal that Trump seems so desperate to need doesn’t matter much in the long term. Just as Trump’s trade war isn’t really about trade, neither will a trade deal with China solve the deeper clash—about technology and national security—that Trump has brought forth. That conflict predates Trump, of course. However, the president’s actions against Huawei have brought technology-based nationalism to define the US-China relationship in ways it hadn’t in the past. And, more importantly, in ways that are much harder to resolve.

To induce Beijing to sign a trade deal, Trump will likely have to ease up on Huawei even more. To the company, however, that would be seem like a temporary reprieve. Under the Damoclean sword of US policy, Huawei will be racing faster than ever to master the high-tech inputs that now leave it vulnerable to Americans.

That fate dangles over every other ambitious Chinese tech company, too. The new reality is that no ambitious Chinese tech company will feel safe from running afoul of Washington. Far from pressuring China to open up its economy, the Huawei episode will push the government to double-down on its efforts to foster technological autarky, and mobilize Chinese businesses around that effort. That’s liable to leave Chinese tech companies less invested in the liberal world order’s status quo, and far more intertwined with the Chinese state.

Understanding Huawei

Like China itself, Huawei is rife with contradiction.

Huawei (which is pronounced “hwah way”—not, as most English-speakers say it, “wah way”) is an undeniably Chinese company. It was founded in southern China in 1987, by a former People’s Liberation Army engineer named Ren Zhengfei, who boasts of having launched the company with a mere $2,500. It thrived in the 1990s through procurement contracts to build networks in rural hinterlands. (A veteran Huawei equipment salesman who worked on backwater projects in the 1990s recently recounted to me that one of the big tech challenges he faced in those days was mice gnawing through their cables.)

But Huawei sees itself as a global company. Its 188,000 employees live and work in offices all over the world. Last year, barely half of its $106 billion in revenue came from China. Of the regions with the fastest growth, Europe, the Middle East, and Africa topped the list, at 24% versus the previous year. Has it benefited from subsidies and government grants? Sure. But no more so than any other company in China, it argues. To the contrary, Huawei’s leaders emphasize, part of the reason for its global reach—unparalleled by other Chinese companies—is that state procurement policies shunned its products early on, pushing Huawei to scramble for contracts in Russia and Tanzania instead.

With its international footprint and Ren’s savoir faire, Huawei can look not so different from Western tech titans. Back at headquarters, though, its corporate culture is known for being insular and shaped by Ren’s military-themed sloganeering.

China is, of course, infamous for its knock-off economy. Huawei isn’t exactly an exception, as the Wall Street Journal detailed comprehensively in a must-read article (paywall). For example, in the early 2000s, Cisco sued Huawei for ripping off one of its routers so brazenly, it copied bugs in the software code and typos from the product manual, according to WSJ. Huawei settled in 2004, conceding that it had cribbed part of Cisco’s software.

In January, the US government accused Huawei of copying T-Mobile’s phone-dialing robot—better known as “Tappy”—as part of an active indictment (pdf). The FBI’s investigation turned up emails showing that in July 2013, Huawei promised bonuses to employees based on the value of the information pilfered from other companies, according to a US justice department announcement.

Those suspicious of Huawei find it hard not to connect these incidents with the sudden, rapid rise of Huawei’s fortunes.

But more than perhaps any major Chinese company, Huawei also bucks the stereotypical steal-and-improve business model. One of its biggest points of pride is its long-standing commitment to R&D investments—it says it consistently invests at least 10% of its revenue. Since 2015, the company’s earned $1.4 billion from licensing its own patents, it says. Huawei is also famous for paying top dollar to recruit the best university grads and, increasingly, foreign talent. That spending seems to have paid off: Huawei is now a proven innovator and pioneer of industry-leading technology.

An emerging threat?

What about the threat it poses to the US and its allies? To the Trump administration, the answer is clear enough.

“Huawei is owned by the state of China and has deep connections to their intelligence service,” said secretary of state Mike Pompeo in March. “That should send off flares for everybody who understands what the Chinese military and Chinese intelligence services do.”

Available evidence suggests Pompeo is wrong. Sure China is one of the biggest sources of cyberattacks, according to Western intelligence agencies (and perhaps the biggest). But the connection to Huawei is flimsy at best.

Unlike its domestic competitor ZTE, Huawei is entirely private—owned almost entirely by its employees, not the state. The company now includes on the tour it gives visiting journalists the “shareholding room”—a windowless office room in its executive office in Shenzhen that features paper copies of individual shareholding and corporate ballots in a glass display at the center of the room—and invites reporters to riffle through at leisure.

But the matter’s not quite as cut and dry as it might seem. The entity that owns pretty much all of Huawei is an employee trade union that is, by law, affiliated with the state. The company dismisses that concern, and lawyers say it’s unclear what that structure might mean—or whether it’s meaningful at all. The legal hair-splitting might come off as unfairly insinuating.

Then again, Huawei’s ownership oversimplification exemplifies the misrepresentations that the company seems to have a knack for—and that, in aggregate, take the contour of something bigger being hidden. To cite another example, in a January interview, Ren denied that Huawei might spy on behalf of the state. “China’s ministry of foreign affairs has officially clarified that no law in China requires any company to install mandatory back doors,” he told journalists in Shenzhen. “Huawei and me personally have never received any request from any government to provide improper information.” So-called backdoors aren’t the only way of spying, though—and “improper” is a subjective term.

One big catalyst for these conflicts is the world’s impending shift to a whole new mobile network regime: 5G.

5G: a catalyst for profit (and panic)

Think back to the mid-2000s, when 3G suddenly made smartphones and live-streaming possible—or later that decade, when 4G opened up cloud computing, allowed us to stream high-definition TV without buffering, made video calls blessedly unchoppy. It would have been hard to imagine then the ways increased connectivity and speed would revolutionize daily life. Pioneered by the likes of Apple, Google, Netflix, Uber, Instagram and others, that transformation came simply through making phones and other mobile devices able to communicate with each other quickly and seamlessly.

The next phase of network evolution, 5G, promises blazingly fast, uninterrupted connections—allowing us to link countless objects that make up our offline worlds and to turn more and more in-person activities and transactions virtual. Building these networks will take at least a decade and “will be one of the most complex and expensive technology projects ever undertaken,” said Eurasia Group in a November 2018 analysis.

But that’s just the beginning. A massive commercial opportunity awaits those who develop the applications that build off this 5G connectivity. We’ve already anticipated some of these cutting-edge technologies—driverless cars, robot-run factories, and the heretofore dumb objects that 5G will link up to the much-hyped “Internet of Things.” Linking up infrastructure like roads and sewers will create increasingly “smart” cities. Managing these zillions of new linkages will create huge demand for artificial intelligence.

This entire dazzling utopian vision rests on an unsung component. Etched with tiny, dense lattices of electrical switches, chips send and receive whole symphonies of “1”s and “0”s in splits upon splits of seconds, translating the information that runs our smartphones, computers, and, really, any electronic device. Making our world smarter and more virtual will require semiconductors of all types. That includes the cheap commoditized chips that will make your fridge way more perceptive. But it also means we’ll need increasingly awesome chips to take, say, supercomputing to new frontiers.

As it happens, these are all areas of technology that the Chinese government invests heavily in—centerpieces of its decade-long blueprint to wean China off reliance on Western technology. Known as Made in China 2025, this industrial policy is a strategy that Western leaders increasingly demonize as “high-tech mercantilism”—and is a particular bete noire of the Trump administration’s.

This explains also why the Chinese government is gunning hard to be the among the first countries to launch a commercial 5G network, says Eurasia Group. Doing so promises a head-start advantage in developing new high-tech applications.

Huawei should be be key to achieving that goal. But Huawei’s opportunity is also much bigger than that.

By Huawei’s count, the number of people sending and receiving information over its devices already tallies up to three billion. Soon, hundreds of millions more users stand to join that list. And Huawei’s 5G equipment offering is much cheaper—and, some say, more sophisticated—than its main competitors, Ericsson and Nokia. This is why Huawei is attracting customers all over the world. Or, it should be, anyway. But the US has stepped very firmly in the way.

Can’t make it, can’t sell it

Huawei would be running victory laps around its Scandinavian rivals, but for its two Achilles heels. First, despite the furious pace of its R&D, Huawei is still unable to design the highest-end microchips needed to power its state-of-the-art products. As a result, it’s a big customer of American semiconductor companies, which earned $11 billion from sales to Huawei last year (paywall). In time, its own technological catch-up will shrink that reliance, making that first problem surmountable. But the second one might not be. Namely, US national security hawks have long suspected Huawei of helping the Chinese government spy.

Trump has attacked both of Huawei’s vulnerabilities with crippling precision.

Thanks to Trump, national security fears are gaining in popularity and prominence in Washington. Along with the hype around 5G comes a deepening of a potential dark side that the administration has presented: The mass hyperconnectivity 5G offers—and the tremendous amount of data both public and private that it can process—would be a significant national-security threat if that data was running through Huawei equipment.

Over the last year or so, US officials have stepped up pressure on allies to shun Huawei’s 5G equipment, arguing that the hardware it installs—and the updates to the software that runs it—will expose them to the risk of Chinese espionage. Mike Pompeo has even threatened to withhold access to US data from allies that use Huawei equipment. While Germany has so far remained aloof, the UK said in April that it would let Huawei build only non-core parts of its 5G network. Australia, New Zealand, Japan and Taiwan have effectively banned of Huawei from their 5G projects.

Things reached a head in May, Trump declared a “national emergency” on the basis that “foreign adversaries are increasingly creating and exploiting vulnerabilities in information and communications technology and services.” The administration followed up by putting Huawei on an export blacklist, effectively banning US companies from selling it business-critical chips.

The blacklist drama

The problem is this: Like many tech companies, Huawei has come to rely on a truly globalized supply chain. US companies like Qualcomm and Intel sit at the apex of that chain, designing the ultra-powerful chips that transform telephones into dazzlingly fast computers, and carry the data that has supplanted whole urban transportation systems with networks of app-punching strangers.

Though Huawei has been swiftly climbing that supply chain hierarchy, its business still requires the cutting-edge technology of American companies. Huawei says it has sufficient stockpiles of semiconductors to survive for a while. However, Dan Wang, tech sector analyst at Gavekal Dragonomics, is skeptical those are enough to last. “If the US wants to destroy Huawei, it has the tools to do so,” he writes in a recent note. “Huawei has to hope its stockpiles will be able to last enough for the political climate to change.”

Even if that doesn’t happen, a weakened Huawei will still stymie China’s speedy buildout of 5G—and, therefore, the first-mover advantage its companies might enjoy as a result.

But in a move that caught pretty much everyone unawares, on June 29, Trump softened his hard line on Huawei (or seemed to, at least).

After a meeting with Xi Jinping, chairman of the Chinese Communist Party, on the sidelines of the Group of 20 meeting in Osaka, Trump announced that trade talks had resumed, and said that he agreed to hold off on his threat to impose tariffs on an additional $300 billion in Chinese goods. He then said he would start letting US companies sell certain equipment to Huawei again, apparently in exchange for Chinese purchases of US agricultural products. He also said that further talk about Huawei would come only at the “very end” of negotiations.

“We’re talking about equipment where there’s not a great national-emergency problem with it,” Trump said. On Sunday, Trump clarified that his reversal on Huawei policy. “At the request of our High Tech companies, and President Xi, I agreed to allow Chinese company Huawei to buy product from them which will not impact our National Security,” Trump said on Twitter.

But there is so far no official statement on the changes to current restrictions. So it’s unclear what exactly this means for Huawei and its US suppliers—for instance, whether Trump will be taking Huawei off the Entity List—the group of individuals, nations, and companies which cannot buy US technology without special permission from the government.

“All that’s going to happen is the Commerce Department will grant some temporary additional licenses where there’s a general availability,” Larry Kudlow, Trump’s senior economic adviser, told Fox News on June 30, reports the Financial Times (paywall).

Indeed, if Trump’s exempting only sales of parts used in Huawei’s consumer business, the hit to its network equipment will still hurt the company, Paul Triolo, geo-technology analyst at Eurasia Group, told the WSJ (paywall). Network equipment sales to carriers contributed 41% of revenue in 2018, versus 48% of revenue from the consumer segment, according to Huawei’s annual report. However, the margins are thought to be much higher for the carrier equipment business.

To Trump, it seems, Huawei was simply convenient leverage on the issue he truly cares about: signing a trade deal with China.

That’s good news for Huawei and other Chinese tech companies—in the short term, at least. The grimmer news is that the chorus of US leaders that deem Huawei a major threat to national security is growing in number, profile, and bipartisan nature. Trump will certainly face political backlash for folding so quickly on Huawei. For example, Marco Rubio, the Republican senator from Florida, called Trump’s decision a “catastrophic mistake,” and threatened to restore restrictions on Huawei by passing legislation.

And at that, they already have tools aplenty, argues Gavekal’s Wang. The US has already developed a big arsenal of policy tools that could well force US technology companies to cut ties with Chinese ones.

For example, almost a year ago, Congress passed a new law designed to increase scrutiny of advanced technology licensed to China (and other countries, though China was the impetus). The US commerce department is now finishing up a list of proposed “foundational” technologies that are critical to national security—and, therefore, are to be protected under these spiffed up export-control measures. Many analysts expect the administration to name more Chinese tech companies to the Entity List.

Trump’s Huawei policies make more sense in light of his latest announcement: The company is simply a bargaining chip in trade negotiations. A more intriguing question is why so many in both parties in Washington feel so strongly that Huawei is up to no good.

Can Huawei be trusted?

Washington security hawks have for decades suspected—and, on occasion, outright accused—Huawei of helping the Chinese government spy on the US.

But there is no hard evidence (that Quartz has seen) that the company has conducted or facilitated spying on behalf of the Chinese Communist Party. Still, as the Los Angeles Times details in its fantastic profile, there are a couple of stories that are pretty darned fishy.

One involves the African Union’s $200-million headquarters in Addis Ababa, funded wholly by the Chinese government—and for which Huawei supplied most of the IT system (ZTE was also partially involved). Then in 2018, Le Monde reported (link in French) that, every night between midnight and 2am, the AU servers had been transmitting huge volumes of confidential data to Shanghai—and had been doing so since the headquarters opened, in 2012. Huawei denied responsibility, and the Chinese government said it wasn’t involved, calling the allegations “ridiculous and preposterous.” There’s no public proof that the breach came through a backdoor in the system, though, according to Justin Sherman, a cybersecurity policy fellow at the New America Foundation, a non-partisan US think tank. It could have simply been due to security gaps in the Huawei code exploited by Chinese intelligence agents. Even so, not exactly comforting.

Another oft-cited incident took place in January 2019, when Poland arrested a Huawei employee on charges of spying for China (paywall). Wang Weijing, a Chinese national, joined Huawei’s public relations team in 2011, after a stint as attache to the Chinese consul general in Gdansk. The company fired Wang and denied involvement.

Hints, to be sure—but as Huawei and its sympathizers often protest, there’s “no smoking gun.”

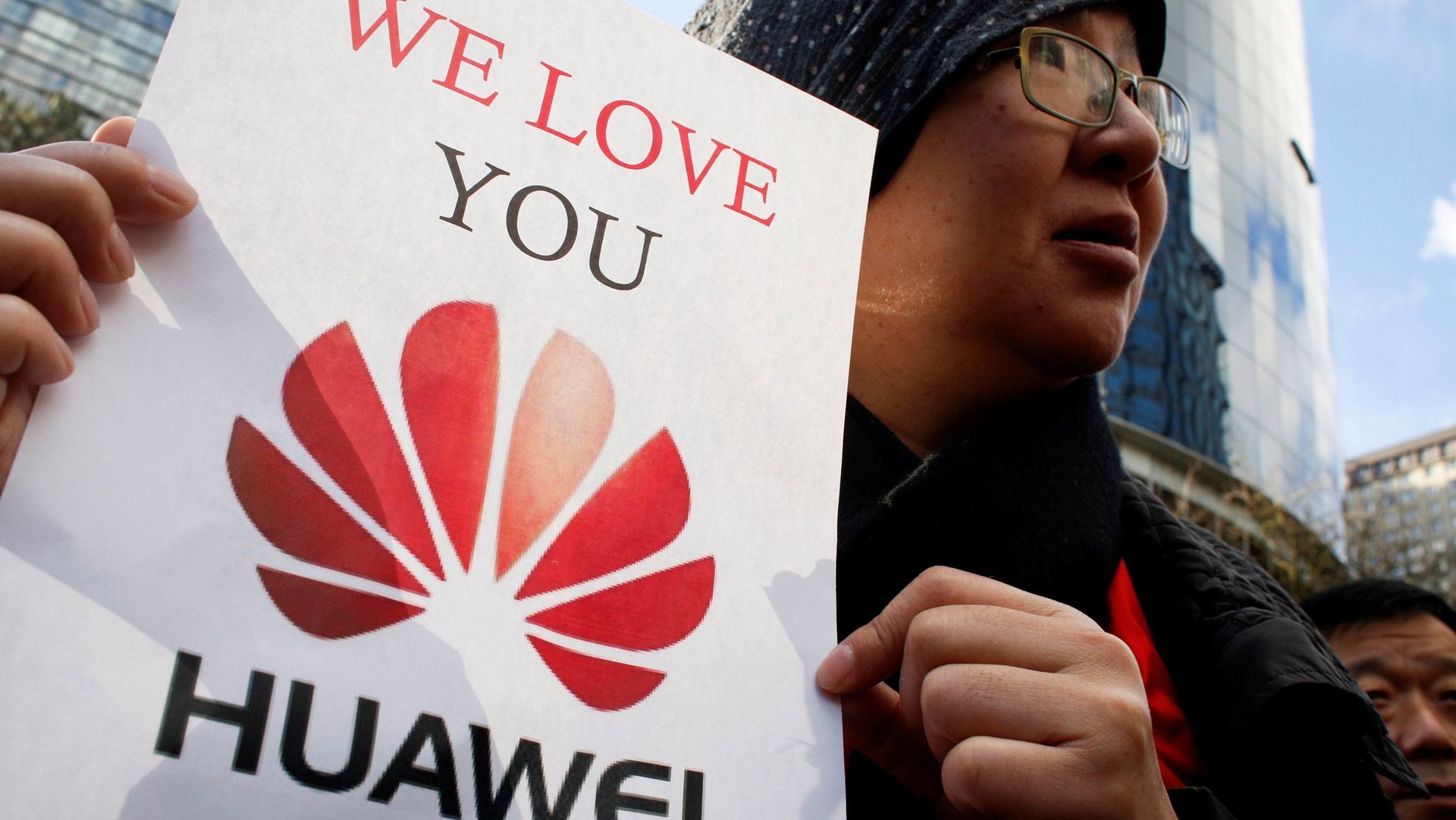

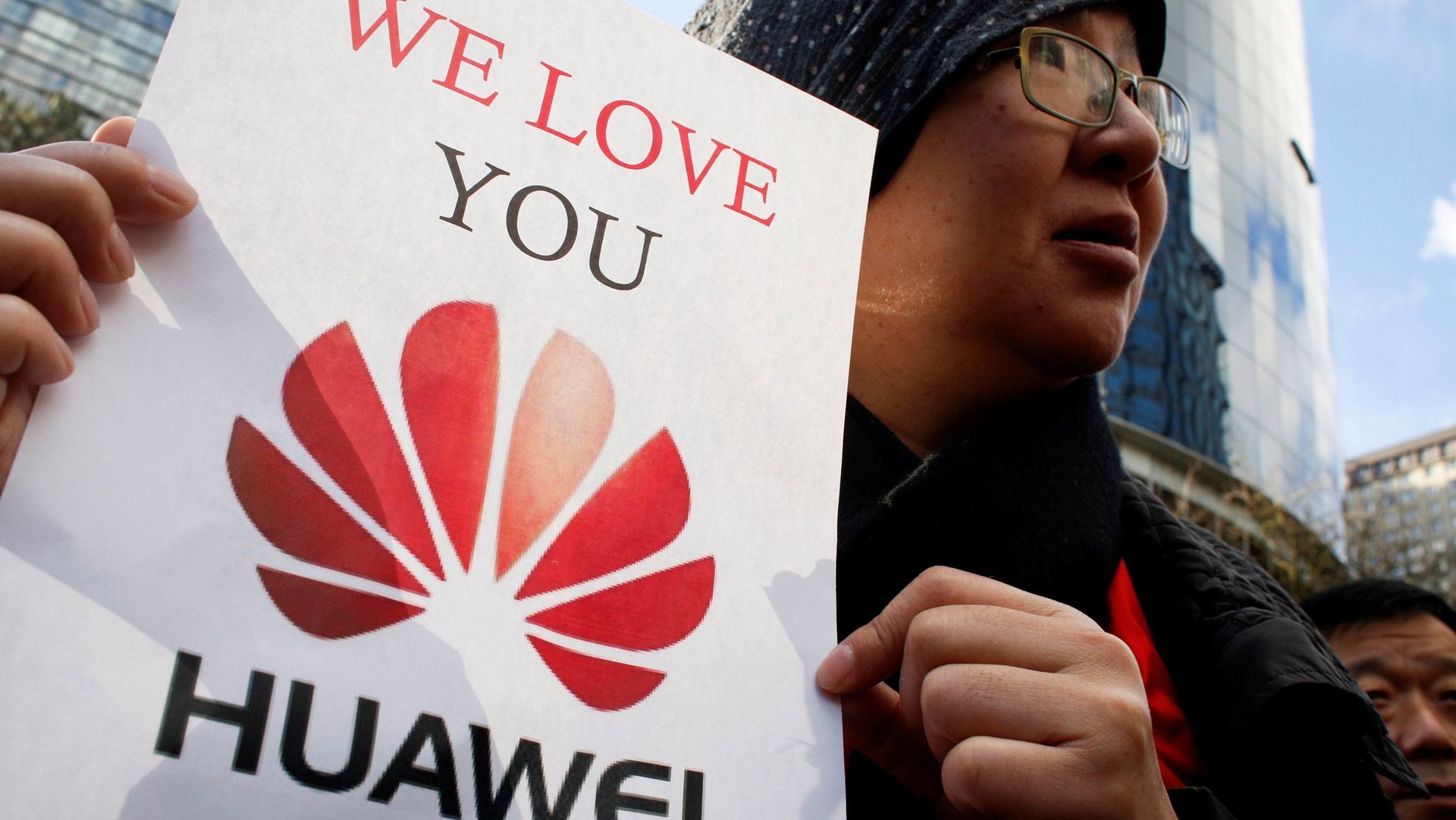

And in fact, this is a big reason why Trump’s moves strike many Chinese thought leaders as savagely unfair—more than simply an effort to “contain” China, they are a spiteful attack on the companies that happen to be China’s best shot at boosting long-term prosperity. For the most part, the Chinese public hasn’t gotten exercised about the trade war, probably in part because Trump’s position is familiar and sympathetic: a strong man standing up for his workers. But the president’s targeting of Huawei has stoked a reaction. Trump is not trying to help US workers so much as hurt Chinese ones, goes the thinking. Instead, he simply wants to keep Chinese people’s lives from continuing to improve.

It’s not hard to see their point. It doesn’t help that the US is hopelessly behind in its 5G buildout, and lacks its own mobile-equipment company that might compete. But that sanctimony also ignores broader geopolitical and technological changes afoot.

For one, as Edward Snowden revealed, US tech companies have complied with their government’s requests to help it spy. Why would China’s be any different? Plus, it’s not hard to see how 5G might change the national security stakes a bit. Along with the exponential increase in the sheer number of devices connected and the data transmitted via 5G, so too rises the risk of breaches. As it is, hardly a week goes by without news of major cyberattacks. The impending technological transformation will increase and intensify these vulnerabilities. The risk could be enough that maybe the gun doesn’t have to be smoking—its mere presence is enough to justify preemptive action.

Huawei pushes back

Huawei is discovering just how hard it is to prove that the absence of evidence is evidence of absence. In an interview in Shenzhen attended by Quartz earlier this month, chairman Liang Hua said the company was willing to sign “no-spy” agreements. CEO Ren has also said he’d shut down his company before he did anything that might hurt his customers. The most common line of defense, however, is that the company abides by the laws of the nations it works in.

In some ways, that’s precisely the problem. A recently passed trio of legislation—covering counterespionage, cybersecurity and national intelligence laws—seems sure to compel companies to cooperate with state intelligence-gathering efforts, on penalty of possible criminal charges.

Huawei’s lawyers insist that those laws don’t actually apply, and lawyers from the British law firm Clifford Chance concur (paywall). As does the Chinese government itself. “China has not and will not demand companies or individuals use methods that run counter to local laws or via installing ‘backdoors’ to collect or provide the Chinese government with data, information or intelligence from home or abroad,” the Chinese foreign ministry told Reuters in March. That seems to suggest that Huawei could shirk any future request from intelligence agents without fear of legal reprisal.

Even disregarding the wiggle room implied in the precision of this statement, the Chinese government isn’t exactly famed for its commitment to rule of law. No matter how deeply Huawei yearns to be a global company that just so happens to be headquartered in China, ultimately, it can’t escape the shadow cast by the Chinese Communist Party’s strength and ambition (which has intensified under Xi Jinping). Unless it picks up and domiciles itself somewhere else, that fact is damning but unavoidable.

There’s one final glaring inconsistency to consider in all this. Even though Huawei insists it’s a private company that operates entirely independent from the state, when Huawei has been attacked or rejected, the Chinese government has struck back.

The Canada backlash

In December 2018, Canadian police arrested Meng Wanzhou—Ren Zhengfei’s daughter and Huawei’s CFO—in the Vancouver airport, complying with an extradition treaty between the US and Canada. The request in question, it turned out, concerned a warrant issued by the US District Court for the Eastern District of New York in August. The Canadian court has revealed that the charges allege that Meng defrauded banks by channeling funding intended for Huawei to Skycom, a company supposedly owned by Huawei that tried to sell equipment to Iran, in defiance of US sanctions. In January, the White House unsealed indictments for nearly two dozen criminal counts against Huawei, including the charges against Meng (pdf). In addition to fingering Meng, the indictments also included fresh accusations of trade theft (this being the aforementioned Tappy affair allegations).

Currently under house arrest in Vancouver, Meng’s extradition hearing should begin in January 2020. She is now suing the Canada Border Services Agency in civil court for questioning her without having advised her of her rights and for unlawfully searching her electronic devices.

In theory, since Meng’s (potential) extradition is a matter for Canadian courts to decide, the matter doesn’t concern the Canadian government. Beijing certainly doesn’t see it that way. Accusing Canada of “Western egotism and white supremacy,” China promptly arrested two Canadian citizens on what seemed like trumped up espionage charges. It also broke with legal norms in imposing the death penalty on two Canadians jailed previously for drug trafficking.

This is by far the most ominous example. But there are others. For instance, when Australia announced a ban on Huawei from its 5G buildout, Chinese customs officials suddenly began holding up Australian coal shipments at ports.

Ironically, those who stand to take the biggest hit besides Huawei happen to be many of America’s most cutting-edge tech companies.

Winners and losers

Let’s start with who stands to benefit from a diminished Huawei, since the list is very short. It includes Huawei’s two main rivals in 5G telecom equipment, Ericsson and Nokia. Ciena, which competes with Huawei in selling optical networking products to telecom carriers, might see an uptick in business. Cisco might similarly stand to benefit.

As for smartphone makers, Xiaomi and Oppo might thrive in the European market if Huawei is forced to cut back in production of high-end models, said S&P Global in a recent note. Overall, though, the prospects for the industry are more mixed. Apple might gain share in Europe, too. Then again, its heavy reliance on China sales also leaves it vulnerable to boycotts or reprisals from the Chinese government.

Samsung faces similarly muddled fortunes. Though it competes with Huawei in both the smartphone and network equipment markets, Samsung also sells smartphone components to Huawei.

If Huawei struggles, Taiwan-based semiconductor foundry TSMC will lose a key customer (which will be exacerbated if Apple founders too). Many semiconductor suppliers—most of them American—will suffer too, including Lumentum, Quorvo, Micron, and Qualcomm.

Elsewhere in America, rural communities could suffer, as they lose what’s been a consistently cheap, reliable source of telecom equipment. For now, major US wireless carriers should be minimally affected. Over time, however, the blacklisting of Huawei will reduce supplier competition globally, which could also drive up costs for US carriers, says S&P Global—ultimately leading to higher mobile service prices for American consumers.

Alphabet will likely take a small hit, too. Since Huawei phones use the Android operating system, the Entity List decision barred Google from continuing to license its OS. That means that even though the Android system will continue to work on Huawei devices, those devices can no longer be updated. The US government announced a 90-day reprieve on the Entity List action. Already, though, carriers in Japan and the UK have halted new launches of Huawei models until the US government clarifies its position.

Now, Alphabet doesn’t actually earn any revenue from licensing Android to Huawei (Alphabet grants Android access for free). It does, however, earn revenue from Play Store purchases made on Huawei phones sold outside China (the Chinese government blocks Google apps and the Play Store). Last year, Alphabet raked in roughly $390 million in revenue from Play Store purchases on Huawei phones, according to analysts at Instinet, the US-based equity trading arm of Nomura Group. Alphabet is unlikely to lose all of that, though, since a decent share of current Huawei owners who switch phones will still use brands based on the Android operating system (and, therefore, will continue to purchase apps via the Play Store).

A new reality

These numbers merely reflect the most superficial exchanges between Silicon Valley and Shenzhen—the transactional part. The long-term contours of the US-China conflict may depend just as much on other, less visible exchanges. “Technology is ultimately something that lives inside people’s heads,” says Gavekal’s Wang, “and the most important way that technology spreads is probably through person-to-person exchanges.”

His point hints at a bigger potential casualty of the Trump administration’s Huawei campaign: American ingenuity. Certainly, the US’s has much greater innovative capacity. But excising Huawei and other Chinese tech companies from America’s technological ecosystem means blocking those tiny iterative exchanges that happen across borders—and that are the ultimate engines of innovation. Thwarting China’s technological progress limits the nation’s long-term economic potential. And, inevitably, America’s too.

Would Trump’s reversal on the export ban—if that truly comes to pass—keep the global tech value chain intact? Probably not. That’s because Huawei, well aware that the US government had a target on its back, has been furiously trying to develop its own hardware and software, to free it from this exact vulnerability. In early June, a Huawei spokesperson said the company was on track to launch a new operating system in China by the end of 2019, with a worldwide rollout coming in 2020. It’s not clear how quickly it’s gaining ground on chip-designing capabilities, but it’s already one of China’s strongest companies on that front. By making that technological leap an existential matter, Trump will only intensify Huawei’s effort to advance.

That effort may well fail anyway. But if Wang is right, killing Huawei won’t snuff out China’s innovative potential. Even if the firm crumbles, its expertise and know-how will outlive it, forming new enterprises and industrial clusters—and, eventually, new ideas. What Huawei’s future will likely influence is whether Americans stand to benefit from those innovations at all.