Will Slack change work before work changes Slack?

On a winter day in 2017, a researcher in Slack’s offices in San Francisco began walking five people through a new version of Slack for the first time. They were testing out a new signup flow designed by Merci Grace, one of Slack’s product managers. It so happened that Stewart Butterfield, Slack’s co-founder, was going over the same prototype in a different room unware of the user testing. Butterfield narrated his experience with the new version of Slack, making suggestions along the way. Grace took notes. Later that day, an employee met Grace to relay the first-time users’ comments. Grace looked down at her notes with Butterfield.

On a winter day in 2017, a researcher in Slack’s offices in San Francisco began walking five people through a new version of Slack for the first time. They were testing out a new signup flow designed by Merci Grace, one of Slack’s product managers. It so happened that Stewart Butterfield, Slack’s co-founder, was going over the same prototype in a different room unware of the user testing. Butterfield narrated his experience with the new version of Slack, making suggestions along the way. Grace took notes. Later that day, an employee met Grace to relay the first-time users’ comments. Grace looked down at her notes with Butterfield.

“Stewart had said verbatim the things those five non-Slack users had said,” she said. “Stewart has put in his 10,000 hours of watching people using software…He has an uncanny ability to predict what someone using a piece of software is going to think. He’s incredible.”

Until Slack, no one had cracked social media at work. For years, Facebook and the iPhone conditioned people to expect the same seamless experience in the office as they had on their own devices. Nothing delivered, until Slack.

It spread purely through word of mouth at first, took root in thousands of offices, and knocked out every major competitor along the way. Brett Hellman, founder of rival app Hall, which eventually was acquired by workplace software company Atlassian, calls Butterfield “the best product designer still practicing.” After Slack arrived, Hellmann taped a sign in his office: “Don’t fight fun,” it said. It was an admission Butterfield was right. Play was redefining knowledge work, and corporate America would never be the same. “I don’t think Slack created the workplace,” Hellmann says. “I think they captured the modern workplace.”

Slack, in simplest terms, is a chat app. Users log in to communicate and collaborate with co-workers in message forums called channels. More than 1,500 apps have already integrated with Slack (second only to Salesforce), enabling users to automate workflows, share documents, create polls, post GIFs, and gather around a virtual watercooler that could span the globe.

But what Slack is selling, Butterfield wrote in 2014, is an organizational transformation he sees as inevitable. Email dominated the last 20 years in the office. Interactions were formal and asynchronous. The next few decades are likely to look much more like Slack. Communication is social. Work is personal. Messaging is instant.

Slack is now used by more than 600,000 organizations, about a fifth of which pay for the service, rather than use a free version, according to Slack’s S-1 filing (pdf). The company is valued at $18 billion after a red-hot direct listing on the New York Stock Exchange on June 20. Revenue has quadrupled to more than $400 million in the last three years (it still racked $140.7 million in losses as it focuses on growth). The company hit $100 million in annual subscription revenue within three years, faster than any enterprise software company in history. Even at that pace, Butterfield argues, the company has barely scratched the surface. “There’s 10 million daily active users, but a couple hundred million people whose working lives are mediated by email,” he said on CNBC. “They would all be better off with Slack or something like it.”

Butterfield’s values are deeply embedded in the design of Slack: play, empathy, craftsmanship, courtesy, and solidarity (all enshrined in the company’s official principles). With Slack now attempting to eclipse Microsoft as the default way the world works, what exactly will that look like? Butterfield’s ideas about how humans should interact emerge from two gaming companies he founded starting in 2002 (and nearly becoming a philosophy professor after graduate school). The first, a multi-player title called Game Neverending, failed to catch on. One of its more elegant features of the game became the basis for the pathbreaking photo-sharing app Flickr. His second game, Glitch, also flopped. Yet it gave birth to what is now Slack. Play was instrumental in both.

One of the reasons Butterfield expects Slack to win is because he understands something fundamental about human nature that his competitors do not. In the end, he argues, humans are playing a neverending game. Fun is tied up with everything we do together. “Infinite games are what we collectively do as a species for building culture,” Butterfield argued a few months after launching Slack in 2014. “It’s fundamental for human beings, as deep a desire as hunger and thirst and sex.”

He wants to make it explicit in our working lives. The question is if Slack can fundamentally change who we are at work before the corporate world forces Slack to look more like itself. There’s already signs of Slack’s quirkiness in retreat. Playfulness has lost prominence in marketing materials. The way the company talks about itself is shifting. Its self-image online has changed. One of its early home pages displayed a snapshot of NASA’s Mars rover touting the space agency’s use of Slack (Aug 2016).

Today it’s anodyne corporate productivity speak: “the power and alignment you need to do your best work.”

Let the game begin.

Stewart Butterfield is ¯ _(ツ)_/¯

We are profoundly influenced by the tools we use. Consider how Facebook’s elevation of “engagement” above all else has affected our mental health, and the body politic. Butterfield has a different set of ideas about how humans should interact online. It emerged from a different upbringing than most.

Born Dharma Jeremy Butterfield in 1973, the future Slack CEO spent his early years in the sleepy, 500-person former fishing village of Lund, British Columbia. His father had escaped the Vietnam War draft in America, and met his wife in Canada. The two joined the back-to-the-land movement, settling in a log cabin in Canada’s hinterlands, where they lived without running water until Butterfield was three. Electricity came a year later. But life there didn’t jibe. “We had a lot of ideas when we were young about building this whole new society—which in a way we did,” Butterfield’s father, David, told Wired in 2014. “But the truth of it was that that society wasn’t any better than the society we left.”

So they decamped for the coast, bought a home in the British Columbia’s capital of Victoria, and re-embraced capitalism. Ther building renovation business thrived. That gave seven-year-old Butterfield the chance to play with an early Apple computer, which he used to teach himself to code. At age 12, he legally changed his given name to Stewart.

Butterfield studied at Canada’s private St. Michaels University School and later pursued two philosophy degrees, the second a Master’s at Cambridge. His professors warned him against a career in philosophy, predicting a wave of PhDs would swamp the academic job market. Meanwhile, the dot-com boom was just beginning. “People who knew how to make websites were moving to San Francisco, and I had a bunch of friends who were making twice as much, or three times as much, as what professors were making,” Butterfield told the BBC in 2018. “It was new and exciting.” Soon, he would join them.

Butterfield had already been playing with the web for years. His entry point was chatting with fellow fans of the jam band Phish on Usenet, an online chat system and precursor to Slack’s own protocol. Eventually, he taught himself HTML, spent a summer building websites, and found his way to a web design agency.

But Butterfield’s career took off with the rise of Web 2.0. By 2004, the internet was shifting from static pages to social and interactive websites. Twitter, Blogger, WordPress, and Wikipedia all asked their users to make, not just consume, the internet. MBAs still hadn’t caught the scent of the coming tech boom, so this next phase of the web’s development was left mainly to enthusiasts and tinkerers making things for themselves and their friends.

In 2003, it was still a hassle to share photos over the internet. Game Neverending, the online multiplayer game Butterfield founded with his friends and then-wife Caterina Fake, had designed a clever way to tag photos and upload them via email. Faced with shutting down the game, the team at Ludicorp, as their company was known, decided to extract the photo-sharing feature as a full-fledged product. Behind this effort was a coder and die-hard Game Neverending fan, Cal Henderson. Butterfield had hired Henderson after the Englishman broke into Ludicorp’s internal mailing list for kicks, lurking there for weeks before declaring himself.

Years before the arrival of Facebook or Instagram, Henderson was pioneering or popularizing a series of firsts on the web, such as tagging friends, social networking, APIs, and photo swapping. It wasn’t long before Ludicorp’s Flickr site attracted the attention of Yahoo. The internet giant, desperate to beat Google at something, snapped up the startup for about $25 million in 2005. But Flickr users, feeling snubbed by the new owners, fled the photo app in droves. Butterfield languished at Yahoo (where he says he learned just how bad corporate software could be), before leaving to start a new game company.

Rescued from the rubble

After he and Fake divorced in 2007 following the birth of their daughter, Butterfield moved to Vancouver to start his second game company, Glitch, with Ludicorp alums. Like Game Neverending, it was whimsical, weird, cerebral, and essential Stewart (game materials are now freely available). Players collaborated on quirky quests and acquired skills from “Transcendental Radiation” (a form of meditation in which the benefits are radiated out to others rather than kept to oneself) to baking. Aggressive players could be sent to chill out in interrogation rooms or exhiled in time out. One could squeeze chickens for sustenance. The game itself was conceived as existing as a dusty speck in the imagination of four giants, including a 13-eyed one named Humbaba.

Glitch, perhaps unsurprisingly, failed to find an audience or profits. (Butterfield himself couldn’t explain the game in less than three minutes.) He shut the game down in 2012, tearfully breaking the news to employees, but once again found a million-dollar idea from in the rubble.

While creating Glitch, the team had built something none of them ever wanted to work without again: a full-featured chat app. One should view most startups’ origin stories as Greek myths—heroic tales designed to elevate a company’s profile rather than the truth. But early employees at Slack say what eventually become the core product was a pretty compelling piece of software when the team first started off in a new direction. Butterfield tried to return his investors’ money, but they refused, betting another Flickr might be around the corner. In January 2013, with millions left in the bank, the team turned to work on their next big thing.

Putting feelings first

What Butterfield says makes Slack different is that empathy, not data, sits at the center of decision making. Silicon Valley is famous for its devotion to data. Tech giants spend millions to optimize their products for advertisers’ clicks. When early Facebook employee Jeff Hammerbacher said the best minds of his generation were devoted to making people click on ads, he was serious.

Slack has the good fortune—intentional, say people in Butterfield’s orbit—of owning a business model aligned with its users’ ends. Customers pay per seat (the lowest tier is about about $84 per year). If they stop using the product, Slack stops charging the customer. That frees them to put the user first (rather than, say, advertisers).

For Butterfield, data is an input, but never the starting point, in the design process, says Merci, who is now a partner at Lightspeed Venture Partners. “The difference between Slack and other product organizations is that data is not the answer. It’s the question,” she says. “If you’re measuring something, what you’ve lost is that human understanding of what this real person is doing. At a scale of millions of people, it’s very easy to stop thinking about this human being, and forget this human experience. It’s not that those things don’t matter. They all matter together…But it’s not that you only care about one metric.”

Sometimes this has frustrated those accustomed to Silicon Valley’s traditional methods. Jessica Kirkpatrick, a senior data scientist at Slack until this February, described Slack’s process as deeply intuitive. “Stewart is very thoughtful about what he wants the product to do in their world,” she says. But it wasn’t an easy adjustment.

“One of the reasons I left Slack was that I didn’t feel data mattered as it would at other companies,” she said. “There were decisions within Slack that felt like they were made because of a principle, even if it was going to hurt aspects of the business, with the idea that being compassionate about our customers, in the long run, was going to make us more successful. It forced me to question my own value and belief in data as having a greater sense of truth.”

Butterfield had to play the role of evangelist internally, spreading the gospel that design process starts with designers’ empathy for users. That’s informed by data, but never reliant on it. That all coverged in the summer of 2016 when Butterfield convened Slack’s product team, roughly 30 designers, engineers, and product managers, at a rented co-working space in Vancouver. In a spare room populated with modern furniture and a handful of whiteboards, Butterfield stood up before his team. Over the next three hours, he talked about the craftsmanship at the heart of Slack. According to employees who attended, his talk was an exploration of product design spanning from the philosophy of 14th-century China to the genius of Eames’ chairs and the art of hospitality, mirroring Butterfield’s own journey from aspiring philosophy professor to software designer.

He compared Slack to a restaurant where guests’ every desire was anticipated and every need catered to. Most people didn’t yet know they needed Slack—most didn’t even know it existed. The last thing they wanted was to learn yet another system of communication. To convince them, Slack’s craftsmanship—its attention to the detail and compassion for the user—had to be deeply personal and flawless. It was emotional design. “Data and user research would never help us solve this question,” an employee recalls Butterfield arguing. “You always have to add judgment to the equation. You can’t delegate to these tools.”

At the meeting, Merci remembers Butterfield playing a video showing a chimpanzee. The primate sat across from a human experimenter who places a marble under one of several cups laid out before them and begins shuffling the cups around. With a flourish the experimenter lifted up a cup to reveal the marble in a place it shouldn’t have been. The chimpanzee rolled back in total surprise and delight.

That primal reaction, one we share even with our distant ancestors, is what Slack wants to elicit while people navigate its product. Only then does it get down to business. “Playfulness is a core value of Slack,” says Merci. “Fun is the business model.”

Butterfield even baked it into the name of the company itself. Plenty of people thought it was crazy to name an enterprise software maker after a word describing what people do when they are not working. “Who’s going to trust their business communications in a product called Slack?” says Hall’s Hellman. “He had such confidence to do that. It was the first company to actually not fight fun. Now it seems really obvious and everyone’s doing it.”

Butterfield calculated our notion of work itself had to change. “Our name may seem funny, but think on this,” the company tweeted in 2014. “Without slack, there is no reach, no play, no flexibility, no learning, no evolution, no growth.”

And that’s the revolution Slack has quietly been nuturing for years. We have spent more than a century, since at least the industrial revolution (and probably far longer), constructing a sense of work and life as operating in separate spheres. Work was a thing you did away from a place called home. We’ve now brought our work home with us, but rarely the opposite. Butterfield believes, to be happy, our whole self needs to come to the office.

If Slack can design the right environment—one that elevates our personal and playful side, communication tools with faces and emojis—it will not only make us more fulfilled, but more productive to boot. “Lots of people have the misconception that there are separate selves, not a single integrated self,” says Merci. “That’s the key insight of Slack in the enterprise context. People at work and at home are not making vastly different decisions. People are mostly making decisions based on emotions.”

Perhaps that’s why Slack holds such wide appeal—not only to digitally focused workplaces (including Quartz) but to couples who use the app to organize their love life, families managing busy households, sandwich shops, and at least one dairy farm. At the same time, the company has breached Microsoft’s defenses winning over multinational corporations: at least 65 companies in the Fortune 100 are now using Slack.

Autodesk, a maker of design and engineering software, is one of them. Since 2015, Slack has evolved from a virtual water cooler to the main communication channel for the firm, says Prakash Kota, Autodesk’s chief information officer. Eighty percent of Autodesk’s workforce is active on Slack. Over the last two months, says Kota, they’ve shared about 160,000 messages per day. (Slack allows for public and private channels for discussions among limited sets of people, as well as direct messages between users or small groups of users.)

“The biggest thing we started to see with Slack was decisions were made more quickly,” he says. Help-bots have automated bureaucratic minutiae. Requests to managers can now be answered in minutes rather than days. Engineering teams are alerted to software outages. More than 8,300 public channels enable employees to socialize and collaborate across 70 locations worldwide. Did rules have to be set up for all this? “We don’t set any guidelines,” Kota says. “We let individuals behave like adults.”

For many companies, that means people chat more, email less, and schedule fewer meetings. Slack says users on paid plans average nine hours per day connected to the app through at least one device, more than an hour and a half actively using it. Fears of an endless watercooler are common, but milling about in chat rooms rather than doing productive work may be more than offset by better collaboration. One 2015 market research (pdf) study found Slack boosted productivity by 32% and reduced meetings by 25%, according to a survey of 1,629 Slack administrators.

Those gains drive growth. Okata, an app authentication service for enterprise workers, says Slack is the fastest growing chat app on its platform. Even among companies paying for Office 365, which bundles Microsoft’s Teams as part of its paid package, 28% of Microsoft’s customers still pay for Slack as well. Okta expects this will continue as teams demand best-in-class software rather than relying on software bundles.

Yet what works at Autodesk, headquartered just outside San Francisco, may not work everywhere. Slack has stumbled as it’s scaled up to companies employing tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of people. Its promise to create a robust, reliable search tool that quickly surfaces crucial knowledge hasn’t quite materialized. Complaints that Slack has become a distraction machine rivaling email are surfacing as well. RescueTime, a productivity app, says the typical knowledge worker now spends 40% of their day multitasking between communication platforms and tasks, with people checking their email and messaging apps on average every six minutes. Over the course of the day, the average worker enjoyed about one hour of uninterrupted productive time.

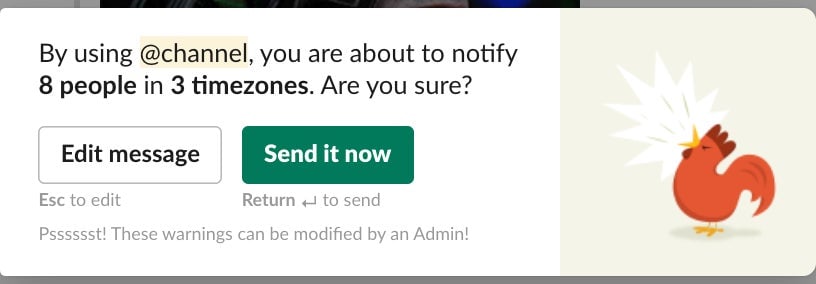

Butterfield blames most of the frustration on a lack of protocols for how to use Slack (or any tools for that matter). Slack offers granular controls to suit organizations’ needs, but few use them to their full extent. “Using Slack (or email, IM, IRC, meetings, phone calls, f2f conversations, CB radios, etc.) inside of a large organization with no protocols or discipline around communication will lead to failure almost all of the time :),” he tweeted last year. “We don’t do a good job of cataloging them (yet) 😔.” The company says it’s still experimenting how to address this. You can already see features such as the “shouty rooster,” which warns users before pinging everyone in a channel.

Jennifer Gibbs, a researcher in the department of communication at the University of California Santa Barbara, suggests the sense of overload already has changed the corporate world’s thinking about chat apps. Managers once worried workers toiling behind computer screens would feel isolated without more interaction with colleagues. “Now the conversation has shifted to the opposite concern, ” she says, “[to] the cognitive and emotional costs of connectivity. We’re trying to help workers disconnect.”

“Culture influences which products are used”

Gibbs studies how large organizations communicate across the workforce. At massive companies, she struggles to make the case for having chat products at all. What’s sensible for small teams can fail at the corporate level, especially when the norms look nothing like the freewheeling ethos of the tech industry where life bleeds into work, and Slack groups are as likely to cater to one’s gender identity as organizing documentation for a steering committee.

Work products that straddle this personal and professional line will hit resistance in corporate America, Gibbs predicts. “Culture interacts with the product itself, so that culture influences which products are used,” she says. “People have developed norms around social media such that it’s used more for personal expressions in ways that are incompatible with the workplace.” Gibbs says many younger people have now become more resistant than older colleagues toward using social media tools in the workplace.

Smaller companies aren’t entirely sold on Slack either, in part because there are so many other options at their disposal. Thor Muller, chief information officer of the Dutch company Off Grid Electric, says he deeply admires what Butterfield has achieved. “My team would probably quit if we were forced off of Slack,” he says. But getting his whole company on board proved impossible. “It really took hold in tech teams, but it really never got adopted by other teams,” he says.

Among most workers at the company’s headquarters, Facebook’s Workplace is the app of choice. Field staff, mainly in Africa, use WhatsApp and Telegram. Video-conferencing software Zoom and Google’s suite are others favorites. Chat is now built into so many products most teams can just take their pick. “There is essentially an infinite number of ways to chat,” says Muller. “This is the conundrum.”

Slack, of course, is more than just messaging. It’s an elaborate philosophy about how to interact online for a common cause. But Gibbs says Slack’s product philosophy isn’t a fit everywhere. It may never be. In Gibbs’ view, the idea that all workplaces will eventually cater to people bringing one’s “whole self” to work is wrong. “I think that’s largely a Silicon Valley thing,” she says. “I find the opposite in most of my research.”

Slack HQ

Visiting Slack’s headquarters in San Francisco, you get the sense no one takes Slack values more seriously than Slack itself. The product’s design permeates the office. Personal art adorns desks. A French rock station plays over the speakers in the bathroom. Every floor is imbued with Butterfield’s mischievous ethos of an endless game no one can lose or quite decipher. Snacks are scattered across different floors to encourage people to move between them. Even the office furniture layout doesn’t follow a straight line. Instead, visitors wend their way amongst rooms designed to reflect a different ecosystem along the Pacific Crest Trail, an epic 2,650-mile path along the ridge of the Sierra Mountains. The engineers inhabit the seventh floor, the forests, full of dark-green potted trees and terra-cotta earth tones. The top is a Sierra summit, rooms that are all light, windows, and carpets tinted the same blue as glacier pools.

The culture lacks the frenetic intensity you often find elsewhere. Employees describe Slack as a company of exceedingly kind introverts. “There are no loud voices at Slack,” says one. “The first chief marketing officer told me this is a company full of dolphins, and we don’t want to hire any sharks.” That’s by design, according to Henderson, the Neverending fan turned Slack co-founder. Candidates were chosen first and foremost for their empathy and courtesy.“It’s more important that this is a person we want to work with long term than are they the best at computer science,” Henderson told Quartz.

As for Butterfield, employees say he frequently shares what books he’s reading, totes ukuleles to meetings, and sends direct messages to staff on their birthdays and anniversaries. He’s tough at times—one employee recalled Butterfield messaging “WTF” over Slack after discovering a product bug late one night—but Butterfield is just as apt to follow up criticism with a hug.

Slack has defied Silicon Valley’s reputation for domineering alpha-males. It has declined to install bro-culture paraphernalia such as foosball tables. Its diversity stats are among the best in Silicon Valley: Women hold 50% of Slack’s managerial roles, and a third of technical positions. Fourteen percent of technical roles are held by underrepresented minorities, that’s compared to less than 5% at Silicon Valley’s major firms, according to federal regulatory filings published by the Center for Investigative Reporting.

All this may help Butterfield achieve Slack’s mission to redesign the status quo for how we interact online. He thought he could do it in games. He ended up doing it at work. Now Butterfield is facing off against the titans of enterprise—Microsoft and Google chief among them—as well as rivals with enterprise aspirations and deep pockets to fund them, like Facebook. He doesn’t seem particularly worried.

“We believe that whoever makes it easiest for teams to function with agility and cohesion in an ever more complex world will be the most important software company in the world,” Butterfield said in a presentation to investors on June 19. “We aim to be that company.”

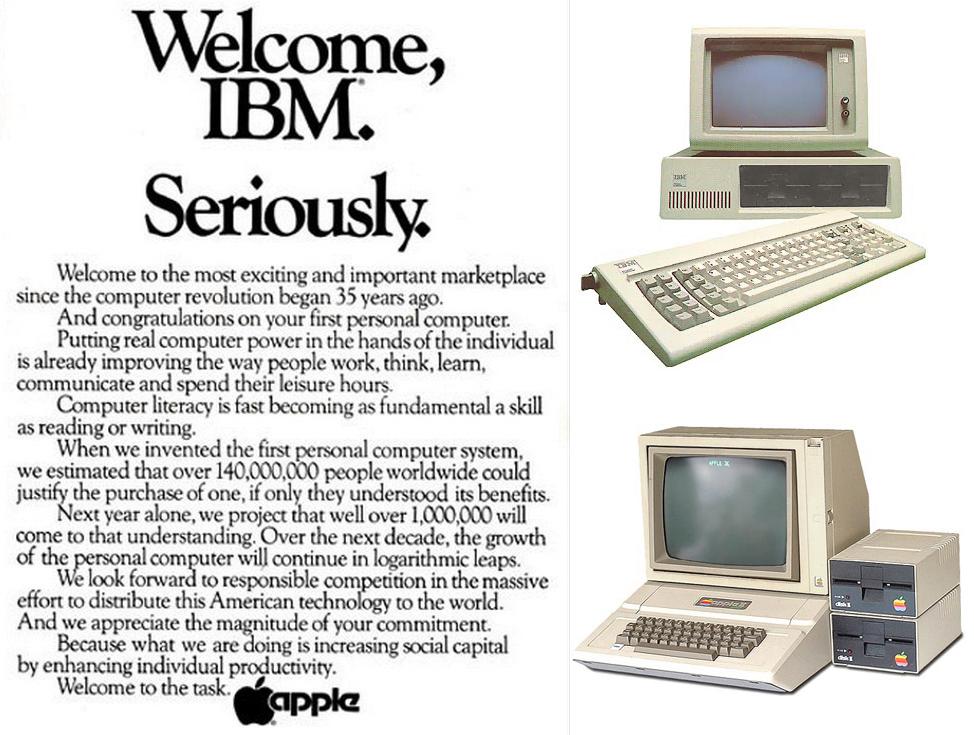

In 2016, Butterfield took out a full-page ad in The New York Times welcoming Microsoft to the market after it launched its rival office-communication product, Teams. Slack’s bet is that it can change the market for business software faster than Microsoft can tighten its grip over the traditional enterprise. Teams has gained traction, but so far, Slack appears to be winning when it comes to chat. “Stewart Butterfield is like the Yankees,” says Hellman, who watched Slack quickly overtake his startup and others like it. “I hope no one runs into him as a competitor. It’s not a fair fight.”

But if history rhymes, Slack may find itself in the wilderness sooner than it thinks. Apple took out a similar ad when IBM entered the PC market in 1981. “Welcome, IBM,” it boasted. “Seriously.” Two years later, Big Blue’s market share had eclipsed the quirky computer maker from Cupertino, which lost its way and wouldn’t recover for years until the introduction of the iPod and iPhone.

Like electricity, or the internet

For Butterfield, the stakes are high. Every year, Gallup surveys thousands of full-time workers around the world. Each time, the results are virtually the same: 85% say they aren’t engaged with their work.

Slack isn’t above declaring it thinks it can change that, even if it’s in small ways at first. “That’s the magic,” he told investors in May. “It’s not just messaging or integrations or collaboration. It’s all of it. It’s helping people work together better than they ever had before: more efficient, more productive, happier…In that sense, Slack is like electricity, or the internet. What problem does electricity solve?”

Over time, as software works its way deeper into our lives, Butterfield wants to capitalize on what he calls the “highest purpose” the internet can ever serve: creating a network in which everyone can meaningfully interact with each other. Slack lets people express their whole selves. Decisions become more transparent. Collaboration is effortless. You may even feel less alienated and disaffected as part of a team. Just like all those games Butterfield used to make long ago.