Overfishing doesn’t just shrink fish populations—they often don’t recover afterwards

Thanks to surging demand for seafood and woefully inaccurate catch reporting, overfishing is out of control. And new research now argues (paywall) that it’s a problem that, in many ecosystems, might be permanent.

Thanks to surging demand for seafood and woefully inaccurate catch reporting, overfishing is out of control. And new research now argues (paywall) that it’s a problem that, in many ecosystems, might be permanent.

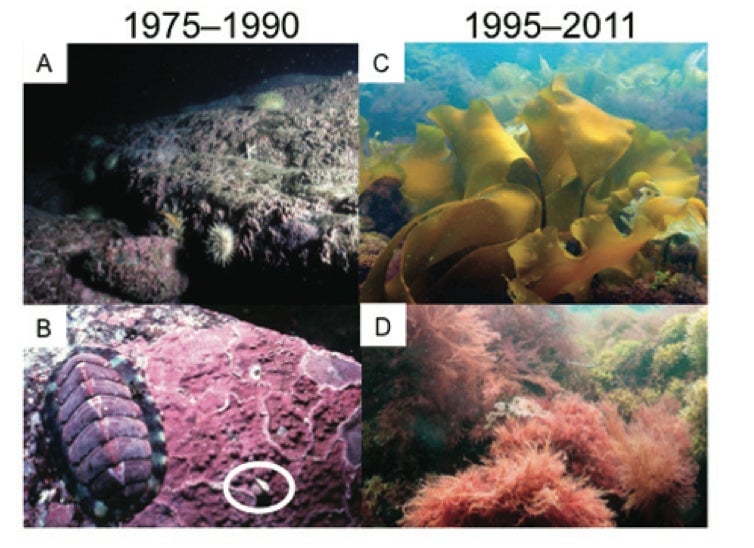

By removing one of its species, overfishing “flips” an ecosystem into an “alternative state,” explains the University of Maine’s Robert Steneck, one of the report’s authors. It sets off a complex reshuffling among remaining species. Often, this “locks” the ecosystem into a “alternative stable state”—meaning, the species of fish can’t come back.

This could have devastating implications for the world’s food supply. “Ecosystem flips and locks that convert the ocean to a bacterial soup that favors jellyfish rather than finfish will not sustain the protein we need to feed the 9 [billion to] 11 billion people expected to show up on Earth over the coming decades,” says Mary Power, of the University of California, Berkeley, who co-authored the study. Here are some examples:

The Maine sea urchin’s boom and bust

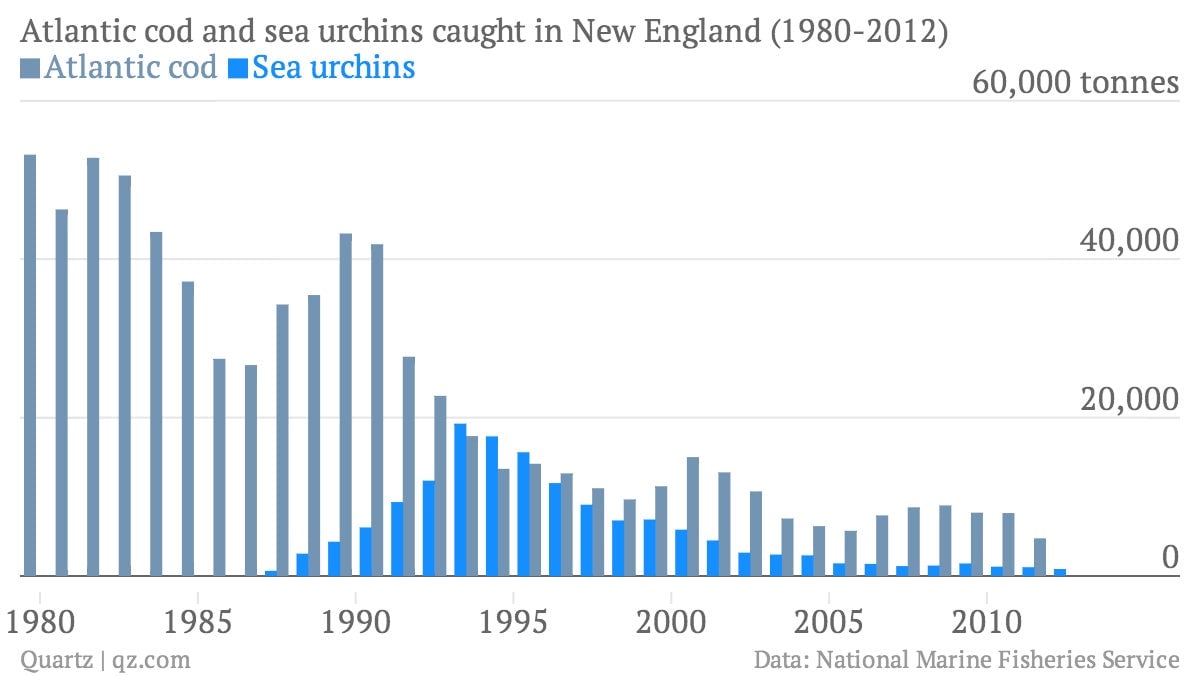

In the 1980s, overfishing crashed the population of the North Atlantic’s once plentiful cod. Without cod to eat them, sea urchin populations exploded.

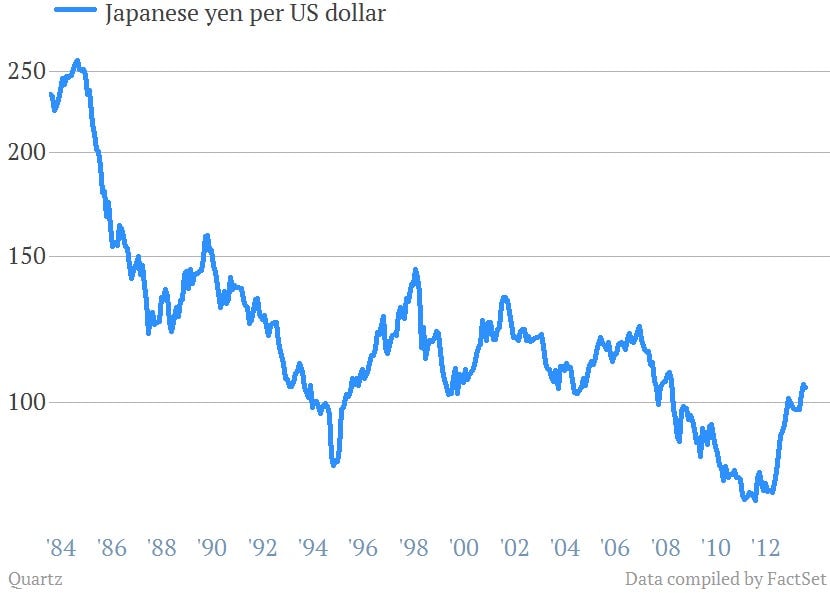

New England fishermen considered urchins a nuisance; they clogged lobster traps and destroyed kelp beds. Japanese, on the other hand, love “uni,” as urchin sushi is called. Buoyed by the yen’s strengthening against the dollar after the 1985 Plaza Accord, Japanese traders from halfway around the world thronged Maine docks, paying in cash—and turning the pests into spiny little gold mines.

Maine’s urchin business ballooned into a $30 million fishery; in 1993 fishermen harvested almost 20,000 tonnes (22,046 tons)—clearly too many. As the urchin population crashed, seaweed, which urchins eat, ran wild, allowing crabs an ideal hiding place from predators. As their numbers swelled, crabs devoured any urchins still left around by fishermen. That’s making it near-impossible for urchins to come back.

From millions of tons of sardines to 12 million tons of jellyfish

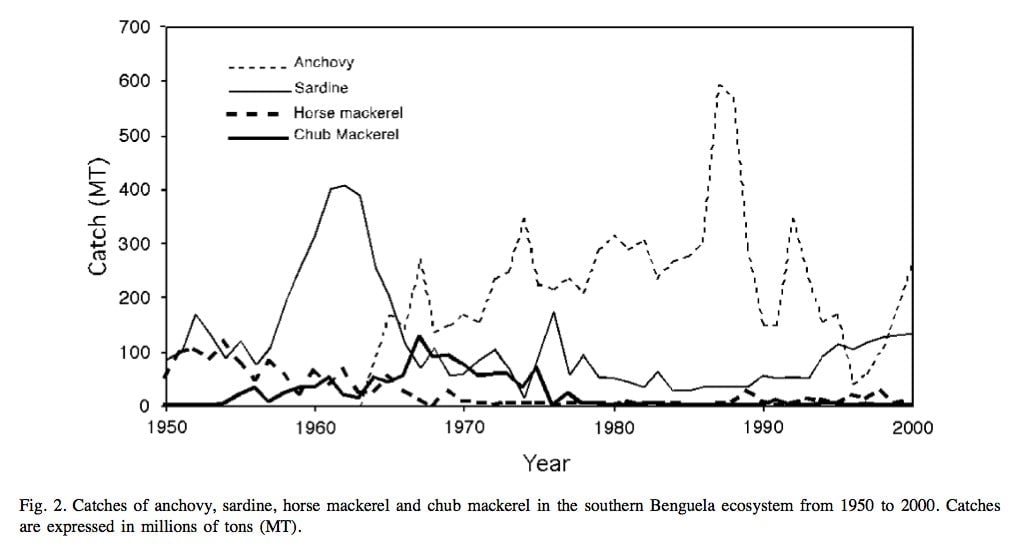

The Benguela ecosystem, off Namibia’s coast, once teemed with sardines and anchovy. Since those little guys are packed with protein, they fed bigger animals like sharks and sea mammals. Their abundance made Benguela among the most aggressively fished ecosystems in the world—such that, by the late 1990s, there were hardly any sardines or anchovies left. Plankton exploded, stripping oxygen from the water.

Enter the jellyfish, one of the only creatures that thrives in “anoxic” conditions.

Sardines and anchovies had once kept jellyfish populations in check by gobbling up plankton, which jellyfish also eat. Worse, jellyfish also fed on the eggs of the remaining sardine and anchovy population. That’s why, by 2006, the northern Benguela waters teemed with 12.2 million tons of jellyfish—and just 3.6 million tons of fish. In turn, populations of penguins and cap gannets, which ate primarily sardines and anchovies, plummeted by 77% and 94%, respectively.

Not enough fish

Why does this keep happening? Steneck cites an increasingly industrial fishing industry—and blissfully unaware consumers. “What we have today are multinational fleets of ‘roving bandits’ that conduct serial depletions and move to more productive grounds,” he says. “People in the US are insulated from the reality of overfishing by seeing fish well stocked in their grocery stores.”