A massive international email scam netted $3 million worth of top-secret US military equipment

A crew of international con artists allegedly convinced a US defense contractor to send them millions of dollars worth of sensitive military gear they weren’t even supposed to know existed, according to court documents obtained by Quartz. Some of the items shipped to the fraudsters are not known to the public and are reportedly so top-secret, “even a photograph [is] considered controlled.”

A crew of international con artists allegedly convinced a US defense contractor to send them millions of dollars worth of sensitive military gear they weren’t even supposed to know existed, according to court documents obtained by Quartz. Some of the items shipped to the fraudsters are not known to the public and are reportedly so top-secret, “even a photograph [is] considered controlled.”

The “highly sensitive communications interception equipment” was valued at $3.2 million, and requires a license to export out of the country. The manufacturer is named in legal filings only as “Company B,” based in Maryland. Members of the ring posed as a Navy contracting officer named “Daniel Drunz” to acquire the restricted technology.

Federal contracting trainer and consultant John Wayne II told Quartz the methods used by the alleged scammers were ones he encounters often, but that he has never seen reach this level. All told, the alleged ring made off with merchandise worth $10.6 million, including the $3.2 million in classified gear, far more than what stands to be gained from the workaday phishing attempts Wayne said government suppliers normally encounter. Those, Wayne explained, might result in a $20,000-$30,000 loss and often involve a few dozen hard drives or memory cards.

Along with the classified military communications equipment, the ring acquired $6.3 million worth of LG televisions and $1.1 million worth of Apple iPhones and iPads. The Department of Defense did not respond to a request for comment.

All it took for the scammers posing as “Drunz” to get the equipment from Company B was a free Yahoo email address ending in “navy-mil.us,” per a search warrant application filed in Maryland federal court by special agent August Merker of the Department of Homeland Security’s Counter-Proliferation Investigations Task Force. An authentic Navy email would end in “.mil.”

“Drunz” sent a phony purchase order in August 2016 to Company B for the restricted communications interception equipment, and provided a Chantilly, Virginia shipping address that was described as a Navy installation. Company B delivered the devices a month or two later, after which they were shipped to Los Angeles, California.

The purchase order wasn’t real. Company B never got paid, and when investigators interviewed the employees involved, they informed them that “Drunz” didn’t exist either. “Records searches for DRUNZ revealed that there has never been a U.S. Navy employee named Daniel Drunz,” reads one of the case filings.

Needless to say, the shipping address the scammers provided wasn’t an actual Navy installation, but an ordinary office space. A check with the management company showed it had been rented by a person named Janet Sturmer, who was subsequently picked up by law enforcement. Sturmer has been indicted, along with seven others, on a range of federal charges including money laundering, wire fraud, and aggravated identity theft.

“It is the Department of the Navy’s policy not to comment on any potential or active law enforcement investigations,” US Navy spokesman Ben Anderson said in an email.

There’s always a clue

While it might seem easy for criminals to cover their tracks online, there will almost always be one aspect of a heist that exposes the fraudsters. In this case, court papers indicate Sturmer’s renting of the office was the break investigators needed to connect the dots.

“There’s no substitute for good, old-fashioned gumshoe work,” former FBI assistant director Joseph Campbell told Quartz.

Campbell, who served as a section chief in the FBI’s Weapons of Mass Destruction Directorate, said terrorists and transnational criminal organizations use a variety of methods to obtain export-controlled and dual-use items to either use or resell.

Using a fictitious Navy email was an important tool for the alleged “Drunz” conspirators, but the ring was well prepared in other ways, said Campbell. Finding out the names of the right officials to contact in the first place was important, and writing emails in an authentic-seeming tone perhaps even more so. Accurately mimicking Department of Defense purchase orders was also key, and Campbell said a bit of open-source research can sometimes prove sufficient to this end.

“I’ve seen people pose as a three-star, a four-star general,” said Wayne, the contracting expert, adding that his clients get hit with this sort of attempt on a near-weekly basis.

What to look for

Detecting online scammers means knowing what to look for, and anyone who deals with government contracts should be able to differentiate the protocols of a real US government address from a phony one, Wayne said. And yet, people still get taken.

Certain things should be immediate giveaways, explained Wayne, using a fake purchase order a scammer sent to a client of his last fall as an example.

For starters, Google the number included on the order. If it’s really from the Pentagon (or the FBI or the Environmental Protection Agency or any other legitimate federal entity), it will show up in a search. Unlike many fakes, Wayne explained, federal purchase orders typically use a consistent typeface across the whole document.

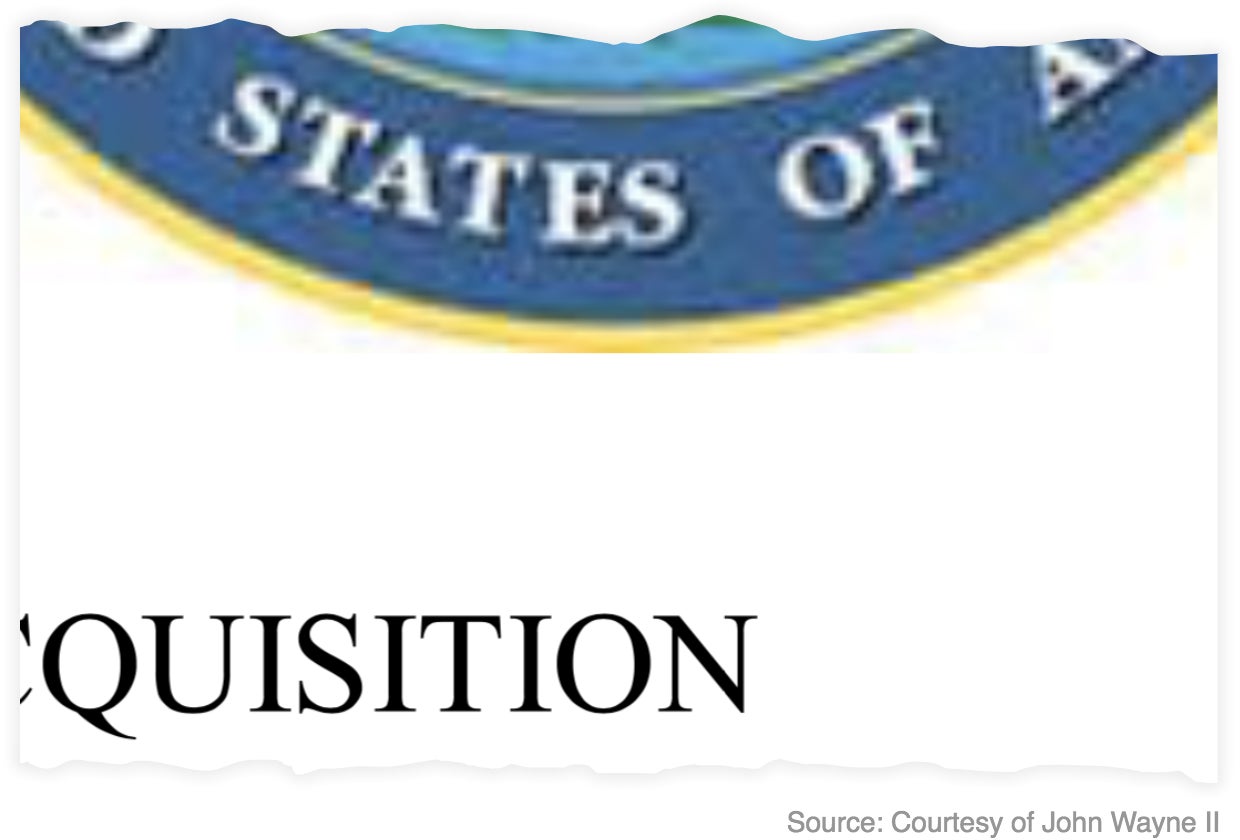

Misspellings are an obvious red flag, as are more easily overlooked details, like the fact that a real purchase order from the US government won’t include payment terms up front. Zooming in on any official-looking seals included in the document may look fine at normal size but can sometimes expose a bad Photoshop job—indicative of a scam.

In the example Wayne provided, enlarging the seal reveals heavy pixelation and rough, choppy edges:

In this case, the scammers were caught. Many times, they’re not. “They’re extremely persistent and time is on their side,” Campbell said. “They’re at this 24/7.”

This article has been updated with a statement from the Navy.