China’s water shortage is so bad it could turn out the lights

China has lost more than an entire Netherlands-worth of wetlands in the last decade—340,000 sq. km, or 9% of China’s total land—to agriculture, development, and climate change, according to new figures from its State Forestry Administration. It’s the latest in a long line of ominous warnings about the water supply in China, which has one-fifth of the world’s population but only 6% of its freshwater.

China has lost more than an entire Netherlands-worth of wetlands in the last decade—340,000 sq. km, or 9% of China’s total land—to agriculture, development, and climate change, according to new figures from its State Forestry Administration. It’s the latest in a long line of ominous warnings about the water supply in China, which has one-fifth of the world’s population but only 6% of its freshwater.

“This will add to the pressure and increase competition for water going forward,” Debra Tan, director of Hong Kong-based non-profit China Water Risk, told Reuters. “China will be looking to grow more food, and more food in wetlands, as urbanization continues.”

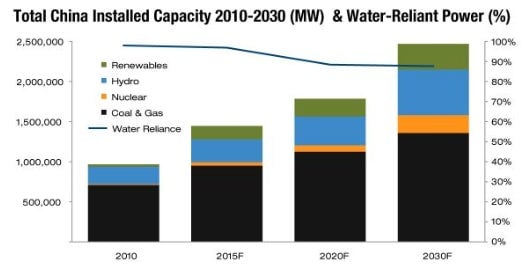

The problems go far beyond China’s people not having enough to drink. The country’s electricity comes almost exclusively from water-intensive power sources—mostly coal, but also nuclear and hydro power—so that a water shortage could easily lead to a power shortage. Mining coal and turning it into electricity already consumes 17% of China’s water supply. And a plan to expand coal production in provinces such as Inner Mongolia—designed to ease air pollution in the country’s heavily populated eastern seaboard—is expected to increase demand for water there by more than double.

If you drill down into the specific regions that are going to get very thirsty, it gets even worse. China Water Risk has identified China’s “Dry 11” provinces—a cluster surrounding Beijing and Shanghai, along with two interior provinces to the west. In total, the Dry 11 are home to more than 510 million people, and they contribute nearly half of China’s GDP:

Policymakers in Beijing are certainly aware of the challenges: They are moving to protect wetlands, increase water fees (paywall) and embark on gigantic engineering schemes to route water from the fertile south to the arid north. But as long as China requires enormous amounts of water to keep the lights on, it may be facing a very dry future—and possibly a dark one as well.