Billionaire philanthropy is being disrupted

For a couple of weeks in late 2018, procrastinators the world over tried their hand at a new kind of electronic time-wasting: virtual mega-philanthropy, via a viral choose-your-own-adventure strategy game. Made by designer Kris Ligman, the game kicks off with a chilling proclamation: “When you wake up this morning from unsettling dreams, you find yourself changed in your bed into a monstrous vermin. You are Jeff Bezos.”

For a couple of weeks in late 2018, procrastinators the world over tried their hand at a new kind of electronic time-wasting: virtual mega-philanthropy, via a viral choose-your-own-adventure strategy game. Made by designer Kris Ligman, the game kicks off with a chilling proclamation: “When you wake up this morning from unsettling dreams, you find yourself changed in your bed into a monstrous vermin. You are Jeff Bezos.”

Over the course of the following 30 or so text-only slides, players give away the Amazon founder’s fortune wherever they see fit, rendered at $150 billion in liquid terms at the time of the game’s inception. In the swipe of a few keys, you might hire 100,000 new teachers for four years each; end homelessness in the United States; and double the median Amazon worker’s salary to $56,000 a year. Doing so, according to the game’s author, would set Bezos back approximately $58.2 billion—a colossal sum, but one that would likely make no meaningful difference either to the man himself or many, many generations of his descendants. The estimated $55 million required to bring clean water to the town of Flint, Michigan, is about what Bezos earns in three hours.

“Now that the 15 minutes of fame have worn off, it’s actually not that difficult to understand why the thing worked,” Ligman wrote later, in a VentureBeat op-ed. “Roughly everyone wishes they had more cash to burn, and comparatively few people think it’s OK for a rich dude like Bezos to throw money at shit like private space travel while his own employees live on food stamps.”

Inequality is booming. In the US, the top 1% of earners possess more than a third of the country’s total private wealth; the bottom 50%, by contrast, own around 1%. (This is a global trend: last year, as Oxfam reports, the world’s 2000-odd billionaires got 12% wealthier, as the bottom 3.5 billion people—about half the world—grew 11% poorer.) Inequality and philanthropy are old, comfortable bedfellows; moreover, it stands to reason that large fortunes facilitate, and encourage, huge individual generosity. Right now, philanthropy is more robust than ever—while the simultaneous retreat of governments from funding a vast array of social and cultural initiatives opens plenty of opportunities to give.

Nowhere is this more true than in the US, where giving has been 2% or more of GDP for 30 years. In 1997, the tippy-top 0.2% of Americans with incomes over $1 million contributed about 13% of charitable dollars. Since then, initiatives such as the Giving Pledge have pushed the super-wealthy to make regular, Godzilla-sized donations a habit: Tech donors such as Sheryl Sandberg, Twitter co-founder Evan Williams, and Salesforce CEO Marc Benioff routinely donate in excess of $100 million a year.

For the vast majority of people, it can feel slightly dizzying to live in a world where dozens of individuals have a net worth greater than the GDP of entire nations and the ability to obliterate problems affecting millions of people with the swoop of a pen on a check. When they choose not to, or dispense of their wealth in a way that seems self-serving or ineffective, it seems at best like a missed opportunity, and at worst an abuse of their wealth and privilege.

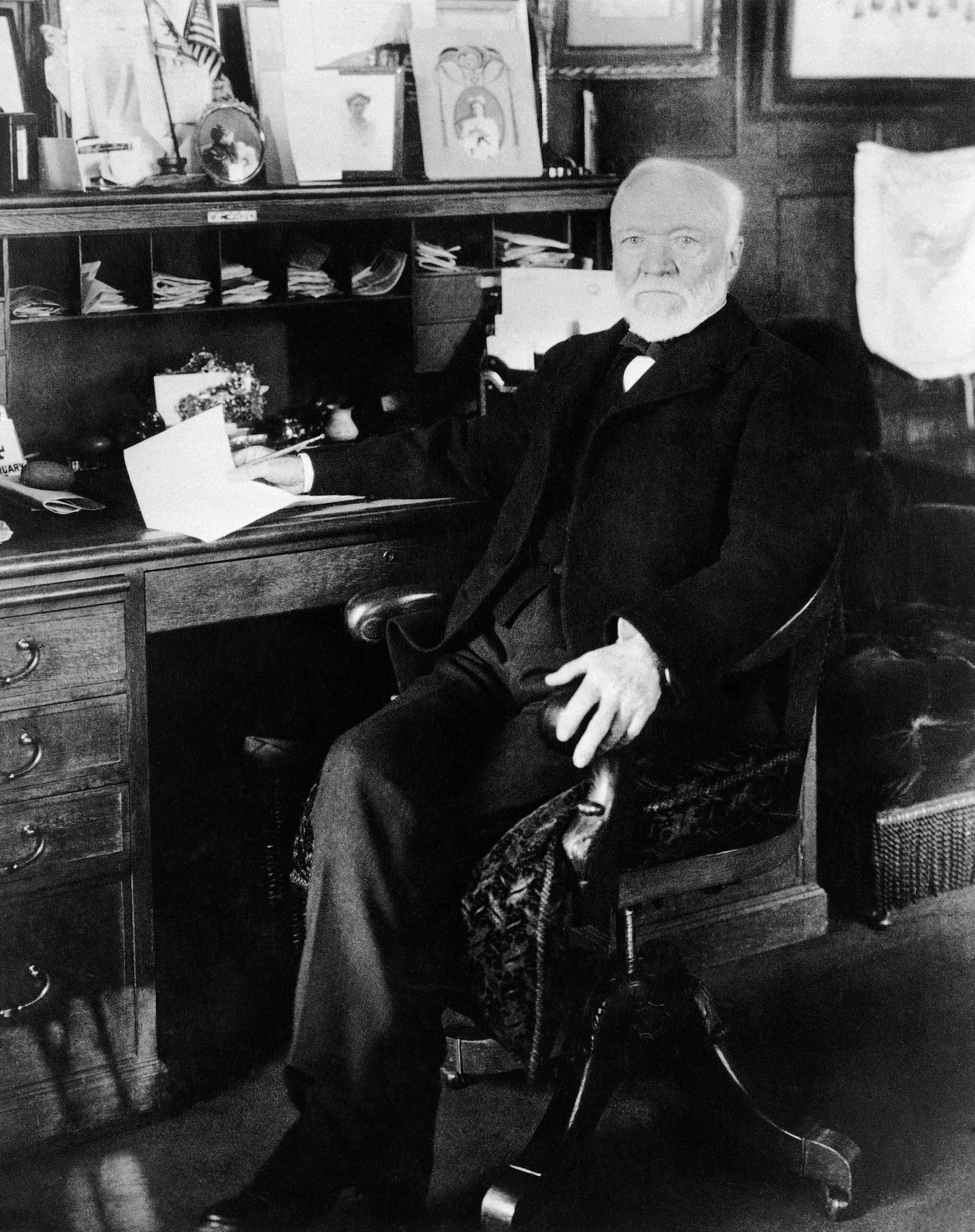

Andrew Carnegie, America’s ur-philanthropist of the Gilded Age, believed there was something very special about the “man of wealth.” The kind of person who could make it big, he reasoned, possessed the “superior wisdom, experience, and ability to administer” that made him uniquely qualified to serve as agent and trustee for his “poorer brethren.” Having amassed vast resources, it was therefore his duty to consider these reserves as “trust funds,” to be carefully doled out during his lifetime to support his community. (Carnegie managed to give away 90% of his fortune before his death.)

More than half of all Americans give at least something to charity each year. Very few can afford to do so on a scale that could actually make a meaningful difference single-handedly (or reroute hundreds of thousands of dollars out of the US tax system in the process.) Increasingly, mega-philanthropists want to be on the front lines of their giving, instead of leaving huge gifts in their will, or even allowing someone else to administer their funds while they get on with whatever made them so rich in the first place. Like Carnegie, they assume that whatever expertise allowed them to become titans in their field may be well-applied to saving the world.

But the public is growing weary of the super-wealthy, and their donations. This group is under scrutiny like never before, with a growing backlash against the traditional forms of philanthropy and billionaire largesse. In the past year alone, three books–Anand Giridharadas’s Winners Take All, Rob Reich’s Just Giving, and Edgar Villanueva’s Decolonizing Wealth—have made an eviscerating case against philanthropy. Their conclusions: It is damaging for democracy, distracts from the varying injustices of extreme wealth (including how it’s made), and often serves as a form of reputation management for the oligarchical class.

At the same time, the scurryings of a new movement in philanthropy are getting louder and louder. This new breed of philanthropy is analytics-focused and results oriented. It relies on data and evidence to decide either where to give, or how to administer funds to make things happen. As the general public calls for philanthropists to be more thoughtful with their giving, an even greater push for change is coming from researchers, academics, and philanthropists themselves.

“We want to burn down our foundation before we die, and ideally well before we die.”

– Cari Tuna, co-founder of the multibillion dollar foundation Good Ventures

Some of philanthropy’s heaviest hitters are leading the charge. Almost from the outset, the Gates Foundation has focused on “lives saved per dollar,” as Bill Gates put it, as a primary measure of effectiveness. Since 2014, it has made all of its peer-reviewed publications publicly accessible, to support other philanthropic efforts. At Bloomberg Philanthropies, “follow the data” has become a key approach, CEO Patricia Harris told Quartz. “We use that data to find unmet needs where we believe we can make a difference and to better focus our funding efforts so we can measure real progress.” For the foundation’s work on reporting US carbon emission reduction to the UN, she said, they worked with researchers at the University of Maryland who employed computer modeling to analyze progress.

And even small nonprofits, such as the family foundation Citrone 33, are adjusting their approach to involve expert consultation and a greater focus on effectiveness. “We no longer, you know, just write checks to whoever will ask—we think about the impact that we’re going to be making,” Gabriella Citrone told a panel at the Milken Institute conference in April.

For perhaps the first time, philanthropists want to be accountable—to suddenly impose checks and balances on a sector in which it has often seemed churlish to look a gift horse in the mouth, let alone ask it for its metrics. Slowly but steadily, all of that is beginning to change.

When altruism goes wrong

Individual philanthropic altruism has long looked something like this: Someone extremely wealthy identifies a problem they would like fixed, a cause they would like to support, or a good deed they would like to facilitate. They write a check, or make a bequest in their will; money eventually gushes forth; they are hailed as a hero; and something may or may not change.

Traditional advocates find plenty to celebrate in this occasionally mercurial approach. “Part of what makes philanthropy powerful and beautiful is its riotous variety,” wrote Karl Zinsmeister, author of the reference book The Almanac of American Philanthropy, in a 2016 defense of charity. “Allowing donors to follow their passions has proven, over generations, to be an effective way of inspiring powerful commitments and getting big results.”

At least in a US context, pluralistic philanthropy of this sort has supported the building of universities, libraries, concert halls, even swimming pools. As early as 1835, the French diplomat Alexis de Tocqueville was struck by the American ability to give en masse. “Americans group together to hold fetes, found seminaries, build inns, construct churches, distribute books. They establish prisons, schools by the same method,” he wrote. “I have frequently admired the endless skill with which the inhabitants of the United States manage to set a common aim to the efforts of a great number of men and to persuade them to pursue it voluntarily.”

It continues to fund things that may be unrealistic (or undesirable) for the state to fund or prioritize—a day at an ultra-accessible water park for a child with a nervous system disorder, for instance, or ProPublica’s Pulitzer-winning investigative journalism. On a more systemic level, philanthropists can afford to take risks business, or governments, cannot, sometimes facilitating striking political change for generations to come. The McCormick family fortune, for example, funded the original contraceptive pill, giving women the right to choose whether to have a family, a career, or both. Now, the Gates Foundation is putting its money behind the development of a better condom and a male contraceptive pill. Philanthropy also played an important role in the civil rights movement, with donors funding the 1960s Voter Education Project that led to the registration of over 175,000 new black voters.

But these are the success stories. Many other efforts have been poorly managed, badly advised, or simply wasteful. In 2010, Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg gave $100 million to set up an education foundation in Newark, New Jersey, a city with which he had no prior connection. Matching gifts from other donors brought the total up to $200 million. Nearly a decade on, city officials now say the gifts were shoddily administered, with more than $20 million shelled out to pay consulting firms across PR, HR, data analysis, and teacher evaluation. Some consultants were paid $1,000 a day. The effect on student learning seems to have been mixed, with improvements in English but none in math.

More recently, a $1 billion Gates Foundation push to assess teachers across the US was found to have neither helped students to graduate nor helped schools to hold on to their best educators. It may even have done more harm than good. (In their annual letter, Bill and Melinda Gates said it had not had the “large impact” they had hoped for, while the “effect on students’ learning was mixed, in part because the pilot feedback systems were implemented differently in each place.”)

“Some charities are hundreds or even thousands of times more effective than others, so it’s very important to find the effective ones. … You could provide one guide dog for one blind American, or you could cure between 400 and 2,000 people of blindness. I think it’s clear what’s the better thing to do.”

– philosopher Peter Singer

More benign giving might simply benefit people who may not really need it, at the expense of those who do. Multi-million-dollar gifts made by billionaire David Koch to cultural institutions such as the New York City Opera, the American Museum of Natural History, and New York Metropolitan Museum of Art might seem as though they benefit a wide range of people. But unless programs are explicitly designed to improve outreach to particular groups, they tend to benefit traditional supporters of the arts, many of whom do not need further support: Studies show “a persistent connection between race, ethnicity, and cultural participation … at traditional ‘high culture’ activities.” (Koch’s own donations have instead been used to support museum collections, such as the Museum Of Natural History’s dinosaur wing, which is named for him.)

As a donor, following your passions is statistically unlikely to lead you to the most effective use of your capital. It seems implausible that, by chance, you’d happen upon the most cost-efficient way to use your resources to help others, or the areas with the greatest need simply by listening to your gut.

Then, of course, there’s the fact that these questions are extremely difficult—and perhaps even impossible—to answer. Take the $13.8 million contributed to ProPublica’s investigative journalism in 2016, for instance. The same sum could buy nearly seven million chemically treated mosquito nets, or enough for half the population of Mozambique, saving approximately 6,000 lives in the process. So, which is more valuable: not-for-profit journalism with demonstrable impact, or more than twice the number of lives lost in 9/11?

Those who support traditional philanthropy, and the right of donors to choose where they spend their money, declare such questions unanswerable, and inappropriate to ask. “Cramped definitions of philanthropy that limit donors to approved areas would suffocate many valuable social inventions,” Zinsmeister writes.

“My ambition now is to do the most good possible with my wealth. To me, this means funding work to safeguard future generations and protect the long-term prospects of humanity.”

– Ben Delo, bitcoin billionaire

But there’s a growing push to ask these questions and others like it, even when initiatives such as these seem impossible to compare. Peter Singer, a philosopher and Princeton professor, is one of the supporters of the Effective Altruism movement, which takes the view that saving as many lives as possible, given the resources available, is the most utilitarian, and therefore best, approach. For them, the malaria nets have to take precedence, for the lives they can save. At the same time, people like Giridharadas might favor the non-profit journalism, on the grounds that is much more likely to bring about structural change for the long term (Giridharadas declined an interview request).

At the heart of these movements, and others like them, are the same questions: What is the most effective way to give? How should we measure effectiveness? And what responsibility, if any, do philanthropists have to be effective donors?

How did we get here?

The expensive business of reputation management

In April 2019, a 15-hour fire obliterated the centuries-old roof of Paris’ Notre Dame. Over a matter of hours, as Paris burned and the world mourned, France’s wealthiest citizens promised hundreds of millions of euros to restore it. (Such gifts, under French law, are subject to a 60% tax rebate.) Perhaps these donations would once simply have been seen as generous; instead, they were met with a swift and uncompromising backlash the world over. The Guardian described them as “ugly”; the Belgian professional golfer, Thomas Pieters, questioned why people would donate to a building when “kids are starving to death in this world.” Broadcasters and Facebook commenters alike wondered whether it was right for anyone to choose a pile of bricks, however historic, over the fates of actual human beings.

Many within philanthropy dismissed these remarks as priggish or ungrateful. Speaking to the New York Times, Nick Tedesco, a senior philanthropic advisor at JP Morgan, marveled: “Instead of praising the act of philanthropy itself, people are saying it’s not the highest and best use of that capital. When did we get to a place where we feel comfortable criticizing other people’s altruism?” (In fact, as of June 2019, these high-profile donors have mostly not come through with the goods, withholding their donations until they are able to have a say over reconstruction plans and contracts.)

“When I look at large foundations making multimillion-dollar decisions while keeping their data and reasoning ‘confidential,’ all I see is a gigantic pile of the most unbelievably mind-blowing arrogance of all time.”

– Holden Karnofsky, cofounder of the nonprofit charity assessor GiveWell

Of course, criticizing philanthropy is not a new phenomenon. Early attempts to set up what would eventually become the Rockefeller Foundation were met with extreme skepticism from the press and politicians alike, and decried as “tainted money” and a “Trojan horse.” (“Huge philanthropic trusts,” one official wrote, were “a menace to the welfare of society.”) In 1911, George W. Wickersham, then the Attorney General, sent a letter to then-president William Taft dissuading him from supporting Rockefeller’s effort, which he called “an indefinite scheme for perpetuating vast wealth” on a scale never before seen, which was “entirely inconsistent with the public interest.” Taft concurred, but the foundation was eventually incorporated via the New York state legislature instead.

Today, particularly as the actions of billionaires receive greater coverage, there is much wider public awareness of what gifts are being given; their huge scale, compared to most people’s means; and the context in which they are donated. This last can make what appear to be generous gifts more complicated. In September 2018, Bezos announced that he would be giving $2 billion away through his Day One Fund, with a particular focus on preschool education for low-income communities and helping the homeless. Earlier that year, however, Amazon paused construction on a new office tower and threatened to sublease space rather than expand in Seattle in protest of a city-specific tax that would have cost the company around $20 million a year. (The city caved.) The same tax would have raised $45 million to $49 million in annual revenue to fund projects for the homeless.

What looks like altruism is sometimes the proxy by which the super-wealthy wield influence and power, especially on politics. “If you don’t favor same-sex marriage or charter schools or shutting down coal plants, you might not be too thrilled with how some billionaires have been deploying their money—subsidized, I should add, by your own tax dollars,” David Callahan points out in his 2017 book The Givers: Wealth, Power, and Philanthropy in a New Gilded Age. “Givers are becoming more powerful while ordinary Americans struggle to get their voices heard at all.”

The wealthy and powerful don’t just have more to give, but a greater incentive to do so: The most recent changes to the US tax code doubled the standard deduction to $12,200 (or $24,400, if filing jointly), resulting in less of a tax break for many lower- or middle-income donors. (For the first time in decades, individual giving declined 1.1% last year, or 3.4% when adjusted for inflation, according to Giving USA data.) As a result, the system actively supports wealthy people wielding their influence.

Philanthropy’s accountability problem

It seems like a reasonable enough proposition: People should be allowed to spend their money on whatever (legal options) they choose. If that includes giving it away, so much to the good. But there are a few complicating factors which have led experts such as Callahan, the founder and editor of Inside Philanthropy, to call for regulating the sector, to make it harder for gifts to sway public policy, or changing tax incentives for different kinds of philanthropic giving according to its actual public benefit. (There is no significant call within government for these sorts of structural changes at present.)

Those within the sector are looking for regulation and accountability from within. To do so, they’re turning to organizations such as of IDInsight, a global nonprofit that helps foundations and governments use “data and evidence to improve the impact of their anti-poverty programs,” its CEO, Buddy Shah, says. Practically speaking, that might mean using anything from randomized trials to machine learning to work out the best course of action to get the job done. (The organization generally doesn’t advise non-profits on what areas to focus on, instead focusing on how best to achieve already identified goals.)

“There’s a lot of complacency in philanthropy. People figure organizations are trying to do good, and that’s enough, even if the results aren’t there. But that’s wasteful and inefficient. It crowds out better programs. So we went looking for the institutions that would tell us about the best approaches to certain problems. It turns out they don’t really exist.”

– Dustin Moskowitz, a co-founder of Facebook and Good Ventures

Perhaps surprisingly, a focus on delivering results is still fairly new, Shah says, even in the most well-intentioned foundations. Charities often don’t have the same strong incentives to succeed that are part and parcel of other sectors, he says. “If you think about accountability structures, foundations are one of the least accountable types of institutions in the world, because they’re basically accountable to their principles.” If those principles don’t include a focus on “honest, hard data on what’s working and what’s not,” it’s hard to prioritize effectiveness, or consider it at all.

In the private sector, by contrast, “market signals” such as profit, revenue, and earnings have a significant impact on investment and how much runway an organization may have, says Shah. And the same is true of governments, whatever their issues: “At least in democratic systems, there’s some mechanism for accountability through elections.” But philanthropy is different. “The incentive structure and the pressure to deliver against a set of predetermined targets—and to update strategy if you’re not achieving those—just doesn’t exist,” he says.

At the same time, it’s extremely difficult to research whether your nonprofit of choice is actually doing a good job, making charities and foundations still less accountable. Colleges and religious institutions remain among the US’s favorite charities, despite being habitually excluded from charity evaluators, which use financial information to judge charities’ soundness. (Religious organizations such as the Salvation Army are exempt from filing Form 990, making it impossible for outsiders to judge its financial health, the effectiveness of what it does, or even where the money is going.) Even then, financial information only tells a small part of the story: a lean CEO salary or healthy program-to-administrative-costs ratio doesn’t necessarily mean that a charity is doing the best possible work.

“In buying Fairtrade products, you’re at best giving very small amounts of money to people in comparatively well-off countries. You’d do considerably more good by buying cheaper goods and donating the money you save to a cost-effective charity.”

– Will MacAskill, Oxford philanthropy professor

Over the past seven years, Shah has seen a gradual move from both new and more established philanthropists toward taking a “structured, evidence-driven approach to making decisions,” in various different forms or degrees of sophistication, he said.

For advocates, it’s a great start, but there’s a long way to go—especially in sifting out the good evidence from the bad. Writing for Inside Philanthropy, Stuart Buck, of the education and criminal justice-focused Laura and John Arnold Foundation, describes how foundation officers are at risk of an “insidious danger, that of thinking that you are making ‘evidence-based’ decisions when, in fact, the evidence is not rigorous or reliable at all.” When the Gates Foundation shuttered its Small Schools Initiative, for instance, they were operating on the say-so of evidence that showed that “shrinking the size of American high schools didn’t work.” Later on, better, more rigorous evidence said the opposite, Buck writes. “Not everything with a line graph counts as “evidence,” and philanthropists need to be more wary of research firms, academics, or evaluation officers who are peddling descriptive charts rather than the results of rigorous randomized trials. Unless they distinguish good evidence from bad, philanthropists will be led in the wrong direction.”

What does the new philanthropy look like?

Here are a few key traits:

Reasoned

When the Gates Foundation first began to plan its philanthropic giving in 2010, it came as a surprise to Bill and Melinda Gates to learn that effective, inexpensive healthcare in the developing world mostly wasn’t being paid for. “We assumed that since it was possible to prevent disease for a few cents or a few dollars at most, it was being taken care of,” Melinda wrote, in their 2018 annual letter. “But it turned out that we were wrong, and tens of millions of kids weren’t being immunized at all.” The $15.3 billion they’ve spent on vaccines since has saved an estimated five million people a year—a staggeringly cost-effective way to save a life. The new philanthropy calls on donors to do their homework—to interrogate their assumptions about what might or might not work, work out what the real problems are, and think hard about whether their money is going to the best possible place.

Collaborative

Foundations and philanthropists are increasingly looking to organizations such as IDInsight and Give Well to help them structure their giving, test any biases, and put them in touch with experts who may have been working in the area for decades.

Global

Philanthropists have often wanted to do good in their community or, at the very least, in their country. The new philanthropy looks further afield, with the underlying assumption that every life, whether in Mozambique or Mississippi, is equally valuable: the key questions, then, are who is suffering the most, and how to help them effectively. Government aid budgets, even if they eclipse what individual donors can donate, are sometimes poorly managed or politically constrained: it often falls to philanthropy to support less well-publicized areas that can be tackled on a huge scale—indeed, global poverty now gets more support from US donors ($39 billion per year) than from official US government aid ($31 billion). The challenge, however, is in finding the problems that can actually be solved: choosing to fund cataract surgery over supporting displaced victims of the refugee crisis, for instance, on the grounds that needless blindness among the poor is a humanitarian crisis that gets far less press—or targeted donations.

Results-motivated

Philanthropy’s success stories are many, but so too are the tales of poorly managed spending that either had little effect on the problem or actually exacerbated it. Randomized trials, stakeholder engagement and data-heavy evidence over a sustained period are now all used to manage impact and make sure that money is being effectively spent. If it’s not working, donors seek a new tack—or an equally pressing problem with easier solutions.

What’s next?

Evidence, data, more evidence and data, and (hopefully) more billionaires putting their fortunes on the line. That’s if the super-wealthy don’t get asked to pay more tax instead, as they’re currently requesting: in an open letter to the 2020 candidates published in June, billionaires such as George Soros, Abigail Disney and Regan Pritzker called for a moderate wealth tax in the “richest 1/10 of the richest 1%.” They could afford it, they said: “We’ll be fine—taking on this tax is the least we can do to strengthen the country we love.”