NASA shake-up leaves space program in confusion

The NASA executive in charge of human space exploration has been ousted over disagreements on the space agency’s plans to land an astronaut on the moon by 2024.

The NASA executive in charge of human space exploration has been ousted over disagreements on the space agency’s plans to land an astronaut on the moon by 2024.

President Donald Trump has asked the space agency to put humans back on the moon before the end of his potential second term in office, but neither the White House nor NASA has won congressional support for the plan. Now, the US space program will attempt to find a path forward without its most consistent figure.

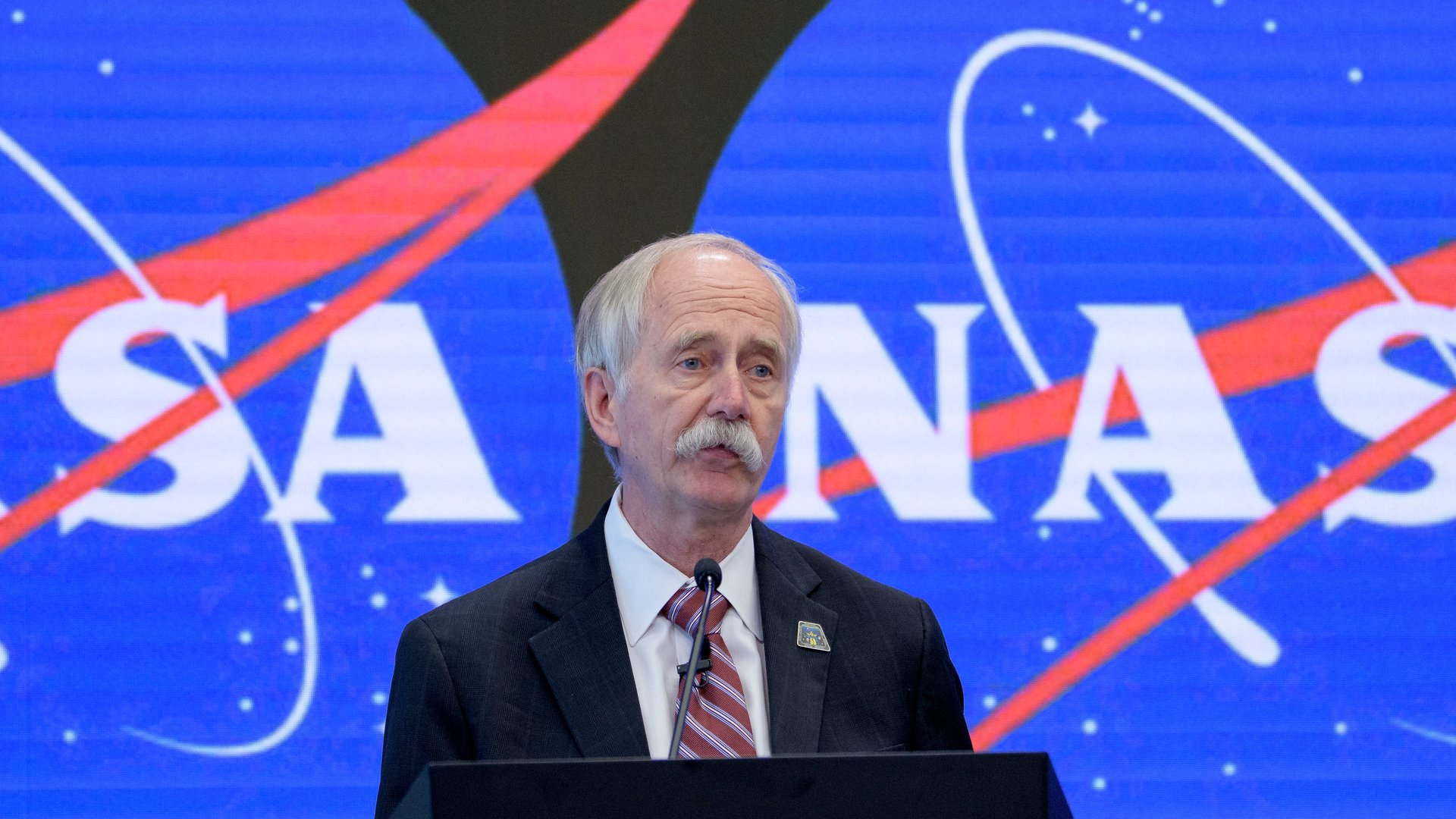

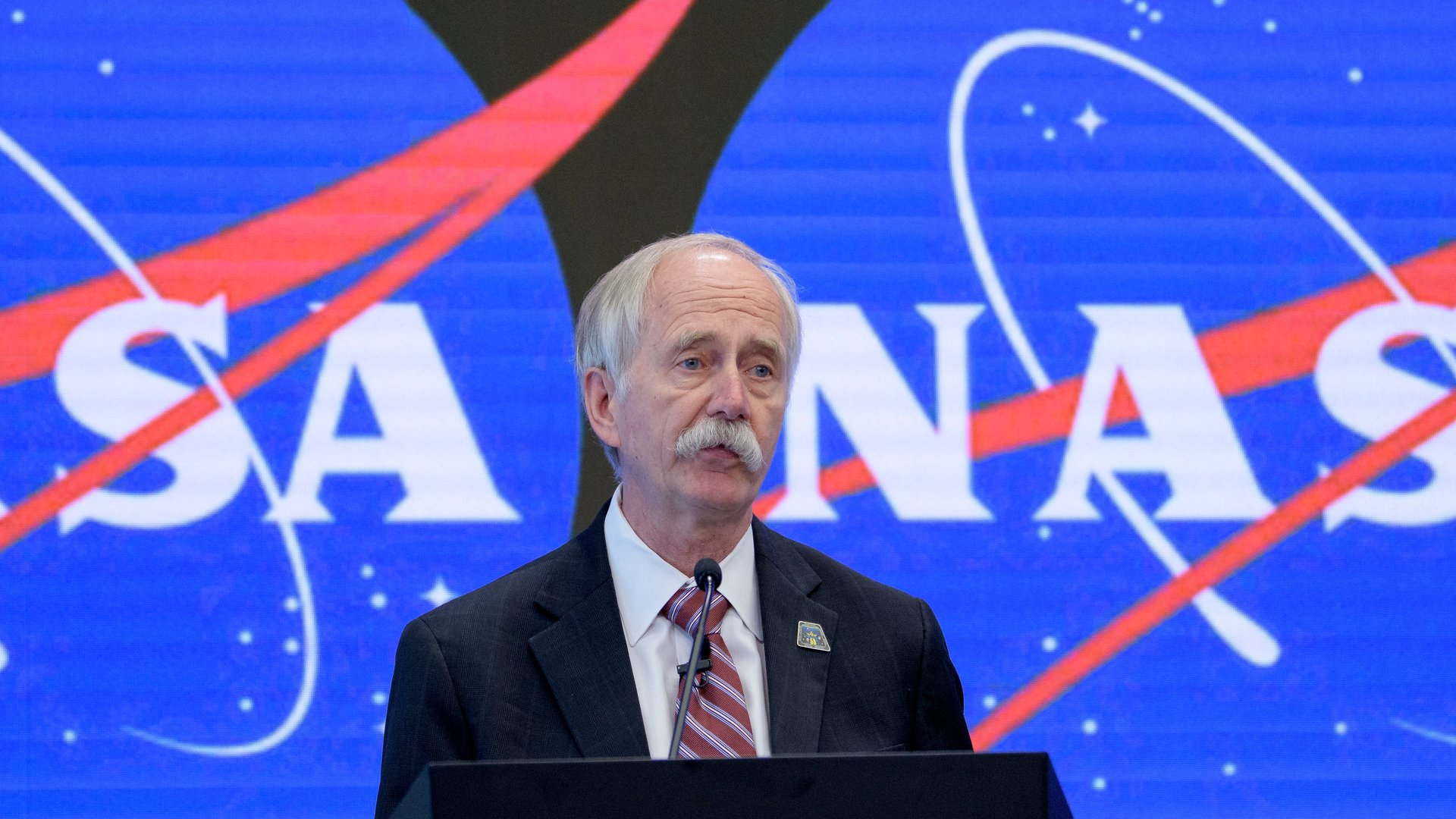

Late yesterday, NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine re-assigned associated administrator William Gerstenmaier and his deputy Bill Hill to “special advisor” positions, and replaced them with Ken Bowersox, a former astronaut, and Tom Whitmeyer, a long-time NASA employee.

Gerstenmaier had been associate administrator in charge of the human operations and exploration directorate since 2005. In that role, he was responsible for the bulk of NASA’s budget: Overseeing the International Space Station, shuttering the space shuttle program, developing NASA’s new deep space exploration vehicles, and transitioning towards purchasing space transportation from private companies.

Few would have been surprised if Gersteinmaier, 65, had announced retirement plans in the near future, but his sudden demotion shocked space program observers.

A baffling decision

NASA did not offer any explanation for the decision other than it was “an effort to meet this challenge” of returning to the moon by 2024, a program dubbed “Artemis.” NASA spokesperson Bob Jacobs did not respond to questions about how the new leadership would better meet the challenge issued by the White House.

Rep. Eddie Bernice Johnson, who chairs the House committee overseeing NASA, said she was “baffled” by the decision, adding that Bridenstine needed to provide a more detailed explanation for his decision.

“The Trump Administration’s ill-defined crash program to land astronauts on the Moon in 2024 was going to be challenging enough to achieve under the best of circumstances,” the Texas Democrat said in a statement. “Removing experienced engineering leadership from that effort and the rest of the nation’s human spaceflight programs at such a crucial point in time seems misguided at best.”

Widely respected by the space agency’s industry, political and academic stakeholders, “Gerst” effectively kept the US space program moving for fifteen years despite contradictory plans from three presidents and seven NASA administrators. Now, he appears to be the scapegoat for structural forces that have slowed NASA’s progress.

“His reign on NASA human spaceflight has been long,” former deputy NASA administrator Lori Garver said of Gerstenmaier. “While this gave some people comfort, it has been a challenge for those wanting to advance change.”

It’s not clear what’s next

In his first remarks in the new role at a space event this morning, Bowersox didn’t deviate from NASA’s existing plans but said changes would be forthcoming. After Trump tweeted in June that NASA should be focusing on Mars, not the moon, there are rumors among agency employees that another policy shift is forthcoming, perhaps linked to next week’s 50th anniversary of the moon landings.

As it stands, few experts believe NASA’s plan for returning to the moon in 2024 is feasible. Congress has yet to endorse the idea, and few lawmakers are expressing enthusiasm. The large rocket called SLS at the center of NASA’s plan continues to face delays. Other required components have just gotten underway (construction of a moon-orbiting way station) or have not even started (building a moon lander or crafting spacesuits suitable for the lunar surface.)

The space agency is caught in a traditional bind between a White House demanding the acceleration of flashy prestige missions, lawmakers that are largely concerned about maintaining jobs and funding for industry partners, and scientists seeking to prioritize research activities.

Some things are working: Science missions continue to provide deep insight into our planet and the universe, and the agency has kept the International Space Station operating and continuously occupied for two decades.

Problems at the top

Efforts to push human exploration farther into the solar system, to the moon and Mars, have lacked a clear mandate, or the funding to achieve what NASA has promised. A large rocket and spacecraft being built by Boeing and Lockheed Martin respectively have been plagued by delays and mismanagement. Some $50 billion will have been spent by next summer, with little to show for it.

Though private companies have successfully replaced the space shuttle for carrying cargo to the space station, their efforts to fly people to the station have also been delayed. The first flights of astronauts on new spacecraft built by Boeing and SpaceX are at least six months away.

Bowersox and Whitmeyer may be able to tweak the architecture of NASA’s moon return plan. Bowersox worked at SpaceX for several years after retiring from NASA, which has led some to speculate he would be more comfortable relying on private firms. But any changes civil servants make will need to be endorsed by both the White House and Congress for the personnel change to yield results.

Outside the agency, some engineers and space advocates argue that the use of commercially available rockets would allow for faster execution of missions. Others believe that abandoning the moon-orbiting way station is key to moving ahead. Meanwhile, policymakers are often concerned about maintaining existing jobs at the agency.

“When we partner with industry, how do we ensure that we don’t take jobs away from our NASA facilities?” Rep. Randy Weber, a Texas Republican, asked in a hearing yesterday.

The pessimistic consensus around Artemis could change with a major shift in NASA’s current plans or a surprise boost in public funding for the project. But time is of the essence: Four and a half years is a short time in space engineering.

Correction: An earlier version of this article misreported the identity of NASA’s top civil servant, which is associate administrator Steve Jurczyk.